National health expenditure data show focus on drug costs misplaced

Prescription drug costs tend to shoulder a lot of the blame for the high and rising cost of health care in America. Bringing down the cost of drugs was the major health care cost control provision in the proposed Build Back Better Act and it featured prominently in President Biden’s State of the Union address. Yet, the latest national health expenditure (NHE) data released this week continues to show this focus is misplaced. The data shows that slower growth in retail prescription drug spending has actually moderated the overall growth in NHE since 2015 and is projected to continue moderating the rate of growth through 2030.

Bad press continues to follow the drug industry

In recent years, drug manufacturers all too often made headlines with stories of outrageous price increases on certain drugs. Of course, in 2015 there was the infamous 5,000 percent overnight hike in the price of a drug for parasitic infections by the hedge fund manager Martin Shkreli. Around that time Mylan Pharmaceuticals was also in the news after they increased EpiPen prices by over 500 percent between 2007 and 2016. Today, rising insulin prices are in the news with calls to cap them at $35.

Hospitals have also received bad press on wild price variations, surprise bills, and aggressive efforts to collect on patient debt. But drug pricing is national and hospital actions are local. People tend to like their local hospital and some people actually donate large sums of money to them. Thus, it’s understandable why these higher profile drug pricing issues might resonate more broadly than even the surprise hospital bills regularly in the news.

With these ongoing headlines and the national scope of the drug industry, it’s easy to see why the public might be quick to focus blame for rising health care costs on drug costs. However, NHE data published annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary tells a different story.

NHE data project health care will continue consuming a greater share of the economy

NHE data provides historical and projected estimates of total annual health care spending in the U.S. broken down by the major sources of health spending, including hospital care, physician services, and retail prescription drugs. This is the “official” estimate of total U.S. health spending used to report the portion of the economy devoted to health care expenditures.

Health expenditures have grown faster than inflation for decades. As a result, health care consumes a greater and greater share of the economy, which then crowds out other spending priorities. Historical NHE data show health expenditures grew from 8.9 percent of the GDP in 1980 to 17.6 percent in 2019.

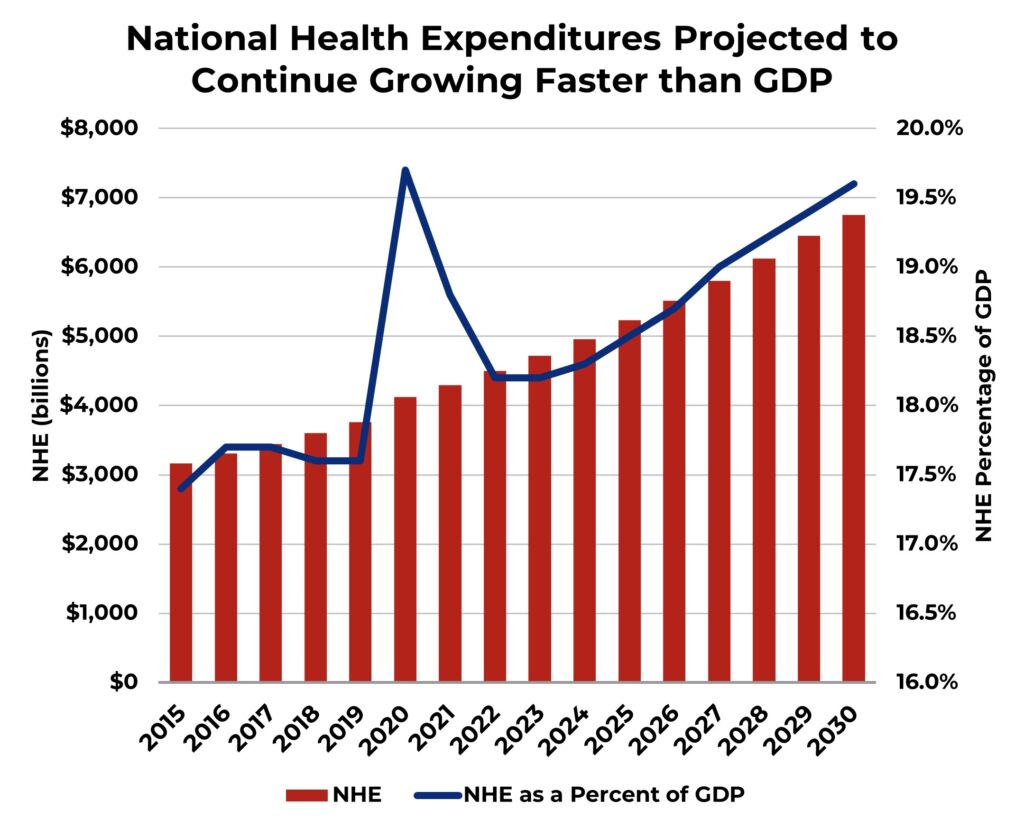

The following figure shows the recent historical NHE trends leading into the ten-year projections that CMS released this week. Health spending as a share of GDP spiked in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic spread. This was due to a combination of higher health care spending on federal COVID-19 activities and lower GDP. After 2022, the effects of COVID-19 are projected to diminish and give way to the traditional trend of health spending rising slightly faster than GDP and consuming a greater share of the economy. By 2030, health care spending is projected to consume 19.6 percent of the economy.

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure Data.

Slower growth in prescription drug spending helps moderate NHE growth

Taking a closer look at the sources of this historical and projected increase in health care spending shows that retail prescription drugs are now helping to moderate the growth. Historically, from the 1980s through the 2000s, prescription drug spending outpaced total health care spending. But that changed around 2010. Since then, with the exception of 2014 and 2015, when expensive medications to treat hepatitis C launched, drug spending has consistently grown more slowly than other major sources of health spending. In fact, from 2015 to 2020, prescription drugs grew at a slower rate than any other source reported in NHE data tables.

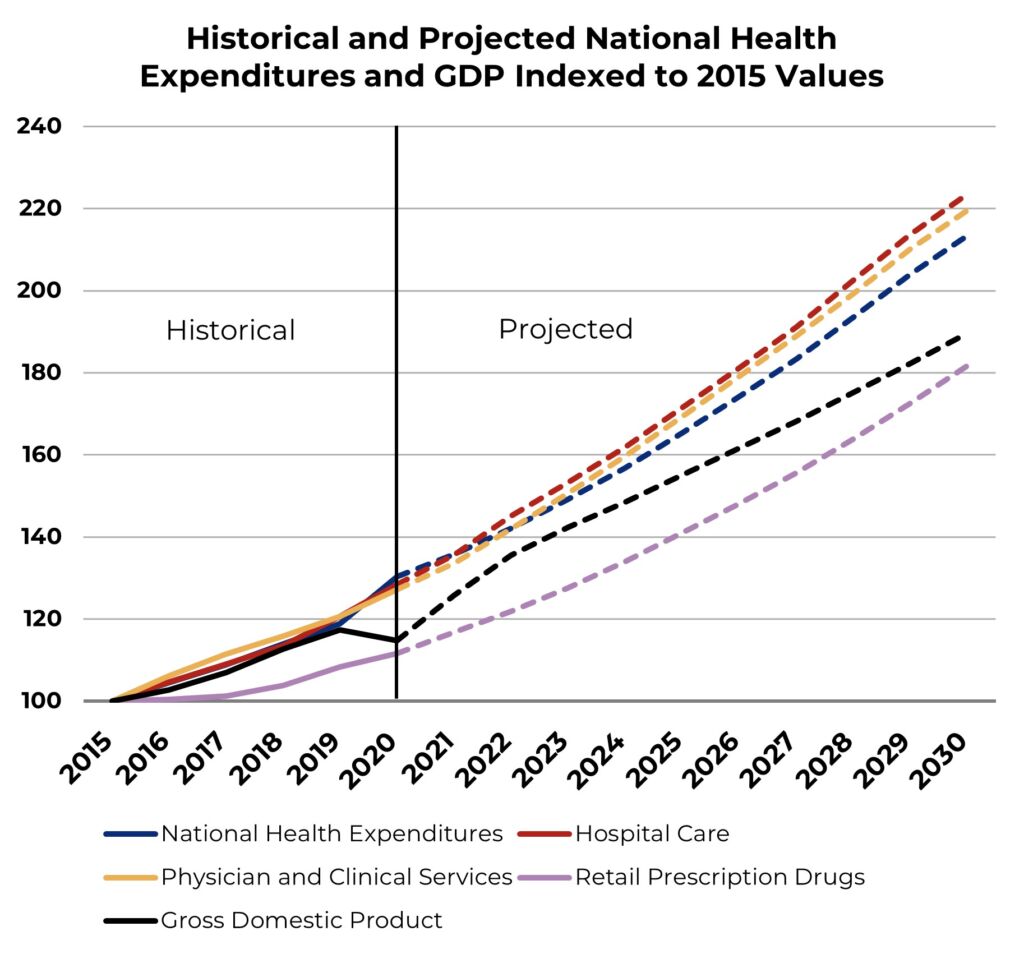

The next figure focuses on historical and projected spending growth in hospital care, physician and clinical services, and retail prescription drugs in comparison to total NHE and GDP growth indexed to 2015. This figure clearly shows retail prescription drugs have been moderating the growth in NHE in recent years. Between 2015 and 2020, spending on retail prescriptions drugs grew more slowly than GDP and, as a result, helped keep the growth in NHE at about the same rate as GDP growth. This kept health care from eating into other spending priorities.

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure Data.

The prior figure also shows retail prescription drug spending is projected to continue growing at a slightly slower average annual rate (5.0 percent) than NHE (5.1 percent) through the 10-year projection period, while hospital (5.7 percent) and physician and clinical services (5.6 percent) are projected to grow faster than NHE. Thus, retail prescription drugs are expected to moderate NHE growth, while hospital and physician and clinical services will accelerate growth.

Prescription drug expenditures remain part of the problem

This does not mean that rising prescription drug costs are not an issue. While prescription drug spending might have helped keep NHE growth from exceeding GDP growth in recent years, this has not been the case historically and, as the prior figure shows, growth in prescription drug spending is projected to exceed GDP growth beginning in 2023 as health spending reverts to pre-pandemic trends. Therefore, growth in prescription drugs will continue to eat into America’s other spending priorities.

The main point to draw from this figure is that the focus on prescription drug costs has been misplaced. It is also fair to say from the NHE data that prescription drug costs pose much less of a problem than growth in spending on hospitals and physician and clinical services. This is true both because drug spending is projected to grow at a slower rate and because it represents a smaller portion of overall spending. In 2020, hospitals accounted for 31 percent of NHE spending and physician and clinical services accounted for 20 percent. By contrast, retail prescription drugs accounted for 8 percent.

As a sidebar, it’s also important to note that the NHE prescription drug spending data only represents retail prescription drug spending. NHE does not separately account for non-retail prescription drug spending, which are generally drugs administered in a physician’s office, hospital or nursing home. This spending is wrapped into the line items for each of these major spending sources. Estimates of non-retail prescription drug expenditures increase total prescription drug expenditures by around 50 percent, which would bring total drug expenditures into the neighborhood of 13 to 14 percent of NHE. It’s not clear from the NHE data whether spending on these drugs are moderating or accelerating NHE growth.

Higher share of out-of-pocket payments for drugs helps explain more moderate growth

There are several possible reasons why prescription drug spending might be rising at a more moderate rate. The NHE data provide at least two insights. First, the NHE’s prescription drug price index that measures the annual change in drug prices shows drug prices actually dropped by 1.0 percent in 2018 and declined again in 2019 and 2020. This is the first decline in drug prices since 1973.

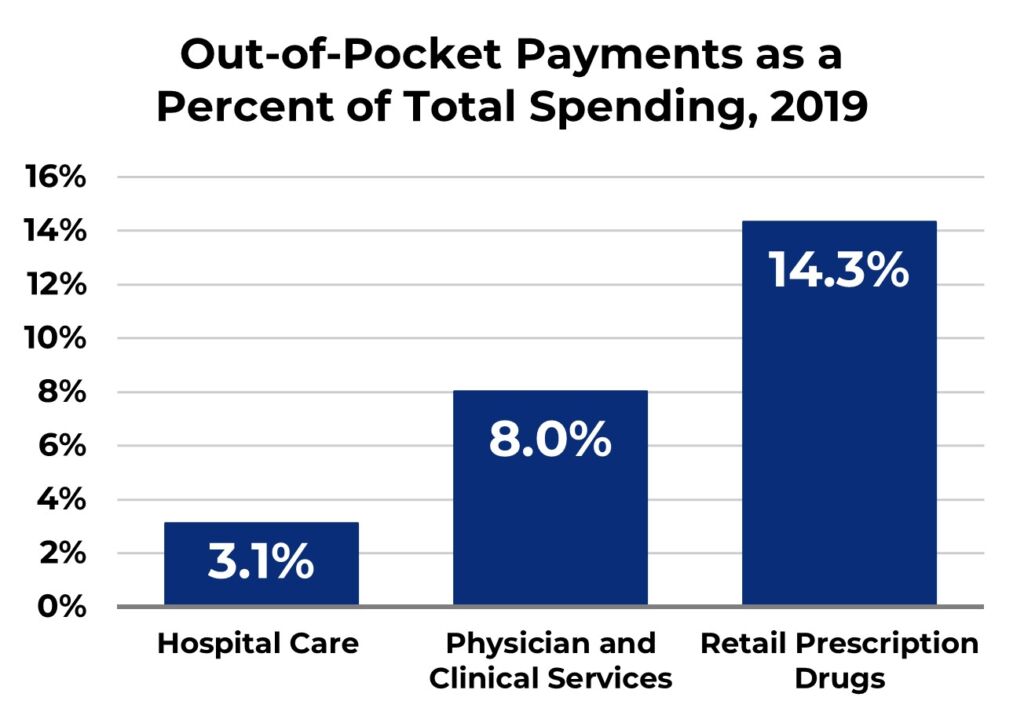

Prices could be down for several reasons, including fewer expensive new drugs coming to market, more generics and biosimilars, and better negotiating by pharmacy benefit managers and health plans. Based on the NHE data, prescription pricing might be held down more so than hospital and physician and clinical services pricing because people pay substantially more out-of-pocket for prescription drugs. As the following figure shows, prior to the pandemic in 2019, out-of-pocket spending as a percent of total prescription drug spending was 14.3 percent. This is substantially higher that the percent of out-of-pocket payments for hospital care (3.1 percent) and physician and clinical services (8.0 percent).

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure Data.

While many people complain about high out-of-pocket cost-sharing requirements, they do bring an important and very positive cost-control feature to the table. When patients pay out of their own pocket, they will be far more price conscious and demand lower prices. The fact that a third-party health plan with less stake in the price pays 96.9 percent of the hospital bill goes a long way towards explaining why the growth in hospital spending consistently outpaces most of the other major sources health spending.

Focus should be on harnessing competition to control costs

Looking forward, the NHE projections show that health care spending is expected to continue growing and taking a greater share of America’s GDP. Thus, cost control remains a large problem, maybe the largest problem facing America’s health care system.

Instead of the narrow focus on drug costs that Congress relied on in Build Back Better, lawmakers need to take a broader view. Historic federal price transparency rules adopted during the Trump administration took this broader view and the Biden administration is moving them forward. Hospitals must now report their pricing, and similar requirements will begin applying to health plans in July. These rules could usher in a new era of price competition to control health costs.

Competition brings efficiency and innovation to every industry, except health care it seems. Lawmakers need to focus on how to better harness competition on broad basis across the health care system. It’s the only path that leads to a better, more affordable health care system for all Americans.