A Primer on How Employment-Based Health Benefits (and the Tax Code) Distort the Health Care Market

Introduction

The Mayo Clinic, over the past year, has convened meetings with some of the nation’s top health policy leaders to develop broadly agreed-upon Action Principles for health care reform. Based on these principles, the clinic recently announced 19 recommendations for health care reform. The lead recommendation is to “move from employer-based insurance to portable, individual-based coverage.” [1] It is a smart and appropriately emphasized recommendation. Very few reforms hold more promise when it comes to reining in costs and improving quality than a transition to individual-based coverage.

However, nearly every American with private health coverage receives health care from an employer; moving everyone to individual-based coverage, where each person would be responsible for purchasing his or her own individual insurance coverage, would be a dramatic change. Something must be deeply wrong with employer-based coverage to inspire such a radical recommendation from the Mayo Clinic.

Indeed, something is deeply wrong. Broad reliance on employers for health coverage distorts America’s health care market in severe ways, resulting in higher costs and lower quality. Employment-based coverage restricts consumer choice, limits market competition, undermines consumer preferences, focuses on short-term health, monitors costs and quality inadequately, and includes more generous benefits than the average employee would buy if given a choice.

These are well-documented and long-running market distortions that health policy professionals have understood for decades. [2] For those who are not health policy professionals, this primer aims to explain those distortions and their negative effects on cost and quality.

Background & History

The emergence of our current health insurance paradigm has been gradual. As a result of financial and legal incentives going back to World War II-era tax breaks, followed by pension law reform in 1973, most Americans have come to rely on their employers for health coverage. People with employer-based coverage get a tax break for medical care costs paid by their employer; people without it, who are proportionally lower income, get virtually no tax break and, on average, miss out on $1,482 per family per year. [3] This unfairness, not incidentally, also provides a strong incentive for employers to continue offering health care benefits insofar as they, too, get a break, by not having to pay payroll taxes on the health benefits they provide. Making employer-based health coverage even more attractive, the Employee Retirement Income and Security Act of 1973 (ERISA) exempted certain employer-provided health care plans from most state regulations and state taxes. Today, over 90 percent of people with private coverage receive coverage through an employer. [4]

The market distortions discussed in this report stem from the fact that few consumers actually pay medical bills out of their own pockets now that employers run the show. Instead, most people rely on their employers (or the government) to make payments to health insurers, doctors, clinics, hospitals, or other providers. This system of payment distorts the health care marketplace by removing consumers (employees) from purchasing decisions. When employers buy health care, they make purchasing decisions with the business’s best interests at the forefront. Those interests — not employees’ — then define health care products. This mismatch underlies every problem discussed in this report.

At the outset, it is important to make the distinction between “group” health plans and “individual” health plans. Nearly all employers that offer health plans provide group plans. Such plans pool the risk of everyone in a group, with insurers then charging prices based on the risk of the group as a whole. [5] Individual health plans do not use employee pools to spread risk. Instead, insurance companies define risk pools much like they do for other insurance products purchased by individuals, such as home insurance and car insurance. Most of the market distortions outlined in this report would fall away if employers were to fund individual health plans instead of group plans. This is the case because — although employers might pay for all or a portion of an individual’s health insurance package — employees would be the ones making actual purchasing decisions. Thus, there would be no disconnect between consumers and purchasers.

How Employers Distort the Health Care Market

As just discussed, because employers pay most of the health insurance bill, they ultimately define the health care products they purchase and, as a result, the health care market responds more to employers than to employees. In other words, the consumer/employee — the actual end user of the health care product or service — plays a secondary role in shaping the health care marketplace. This contrasts starkly with nearly every other market for goods and services. For example, restaurants succeed and fail based on their ability to satisfy the tastes of hundreds of different customers each day. Similarly, computer manufacturers offer laptops of varying quality (titanium case or plastic), features (one gigabyte or two), and prices (as low as $400) to meet a wide range of consumer budgets, lifestyles, and performance needs. Health care markets could operate with the same dynamism and efficiency but do not. Instead, health care markets have become distorted. Because the actual consumer/employee plays only a secondary role in shaping the market, typical consumer-oriented incentives and consumer-derived information no longer steer the market. Consequently, without typical market-steering mechanisms in place, a number of specific market distortions emerge. The distortions outlined below amount to a strong rationale for transitioning to individual-based coverage.

Employment-based coverage restricts consumer choice. Choice abounds in efficient markets (just try counting the number of clothing manufacturers, cell phone models, or realtors from which to choose). Yet when an employer pays for a health plan, there generally is no choice given to the consumer. That’s because, when it comes to buying a health benefit, employers prefer buying a “one-size-fits-all” health plan, which is administratively cheaper and simpler. As a result, 87 percent of employers that offer health coverage offer only one health plan. [6] Even the very largest employers — those with more than 5,000 workers — tend to offer no more than two plans. [7]

With no or very little choice over plans, consumers rely on their employers to make many important decisions about their medical arrangements. Thus, the real person using the product abdicates control over choice of insurance plan carrier, benefits, provider networks covered, cost-sharing, and overall cost of the plan.

Lack of choice limits competition in the health insurance marketplace. The consolidation and lack of competition in the health insurance marketplace can be blamed in part on employers offering employees just one plan. Imagine a world wh

ere employees relied on their employers to pay their restaurant tabs, and imagine each employer choosing only one restaurant chain for their employees. The restaurant marketplace would quickly consolidate around the big chains able to win contracts from big businesses like General Mills, Boeing, 3M, or IBM. How could even a medium-scale restaurant chain survive when big business employees stopped patronizing it? Indeed, its customer base would be decimated. This make-believe world limiting most diners to a Perkins, Cracker Barrel, Applebee’s, or T.G.I. Friday’s would be distasteful, to say the least, but that’s exactly the sort of world Americans accept when it comes to health care.

Lack of choice undermines health insurers’ ability to evaluate consumer preferences. Competition among sellers steers markets to deliver what buyers want. The process works because sellers collect powerful information about consumer preferences based on what consumers buy or do not buy. For instance, the fact that the iPod now holds 68.9 percent of the digital media player market demonstrates what happens when a company pays attention to what consumers want. [8] However, if the new Microsoft Zune begins grabbing market share, Apple product developers most certainly will adapt the iPod to respond to the Zune’s features — maybe its larger screen or wireless capabilities — attracting buyers away from the iPod. The key: Apple product developers will learn in a direct, accurate, and timely fashion, when a buyer leaves the store with a Zune in hand, that their product possibly has a deficiency. The magic of this consumer-driven competitive market is lost in the health insurance market when employers take on the buyer’s role.

An employment-based system — where the buyers (employers) are divorced from the consumers (employees) — eliminates a vital and direct line of communication between consumers and their health insurers. Because most consumers can choose only one plan, they never have the opportunity to switch to a competitor and therefore can never communicate preferences through any sort of purchasing activity. Health insurers are then left without the information they need to design products that meet the demands of actual consumers. Instead, as discussed below, health insurers design products to meet employer preferences.

Employment-based insurance restrains the development of benefit designs and contracts focused on long-term health. In 2006, the median length of time all U.S. workers had been with their current employer was four years. [9] When employees move to new jobs, they must take on their new employers’ health plans; consequently, the average person must jump to a new health plan about every four years. Of course, many employees remain in their jobs less than four years, and thus change health plans even more frequently. With employees jumping from health plan to health plan every time they change jobs, health plan architects are motivated to focus on short-term plan designs and short-term contracts. Yet health care is not a short-term affair. Actions taken or not taken — such as taking blood pressure medicine regularly or eating a high-cholesterol diet — can have lifelong health effects and long-term costs.

Employers do not closely monitor the cost and quality of health plans. While employers do care about costs and quality, they naturally care far less than their employees do. After all, and contrary to assumption, they don’t bear the consequences of poor quality or high cost nearly as acutely as their employees. A delayed cancer diagnosis might cost an employer more money, but obviously it’s the employee who bears the brunt of the problem. Though employers have attempted to assess and control cost and quality, the breadth and reliability of their assessments remain limited. Employers could never monitor the innumerable preferences for varying levels of costs and quality valued by each of their employees.

Furthermore, on the cost side, employers largely offset higher health care costs by paying lower salaries. For instance, research suggests that when state and federal governments mandated that insurance plans cover childbirth, the added cost of the expanded insurance coverage was fully shifted to employees through lower wages. [10]

Employees fail to monitor the cost and quality of care. Though employees are in the best position to determine their own needs and to assess whether their health plans meet those needs, they have far less incentive to monitor their plans for quality, cost, or anything else, because they have little or no power to switch. Certainly, when employees run into problems, they will complain to the health plan and their employer. But their complaints often fall on deaf ears because they’re not backed up by the power to switch to a competitor, which is the consumer’s most powerful tool in any other market for goods or services. It doesn’t take long for an employee with a real complaint, after multiple frustrating attempts to be heard, to become cynical, despondent, and to then give up. It’s not hard to understand why the health insurance industry’s reputation perennially ranks near the bottom, just above the oil and tobacco industries. [11] Scant monitoring by both employers and employees allows health insurance companies to be inefficient, which leads to higher costs and lower quality.

Employers have incentives to offer more costly, benefit-rich health plans. As just discussed, costs rise when employers and employees fail to monitor their health plans, but even a cost-conscious employer has a number of incentives to pick a more costly, benefit-rich health plan. First, when picking just one plan, employers need to accommodate a wide diversity of employee preferences and needs. Second, because out-of-pocket cost-sharing payments for medical services — i.e., premium payments, deductibles, co-payments, and co-insurance — are often paid with taxed dollars, employers prefer plans with lower co-payments and deductibles, which allows them to funnel as much payment as possible through the tax-favored insurance plan. Third, high-wage workers — who are in a much better position to influence a health plan’s design — will, if given the opportunity, push for a more generous plan because they benefit most from the tax exemption and because they tend to be older and thus tend to need more medical care.

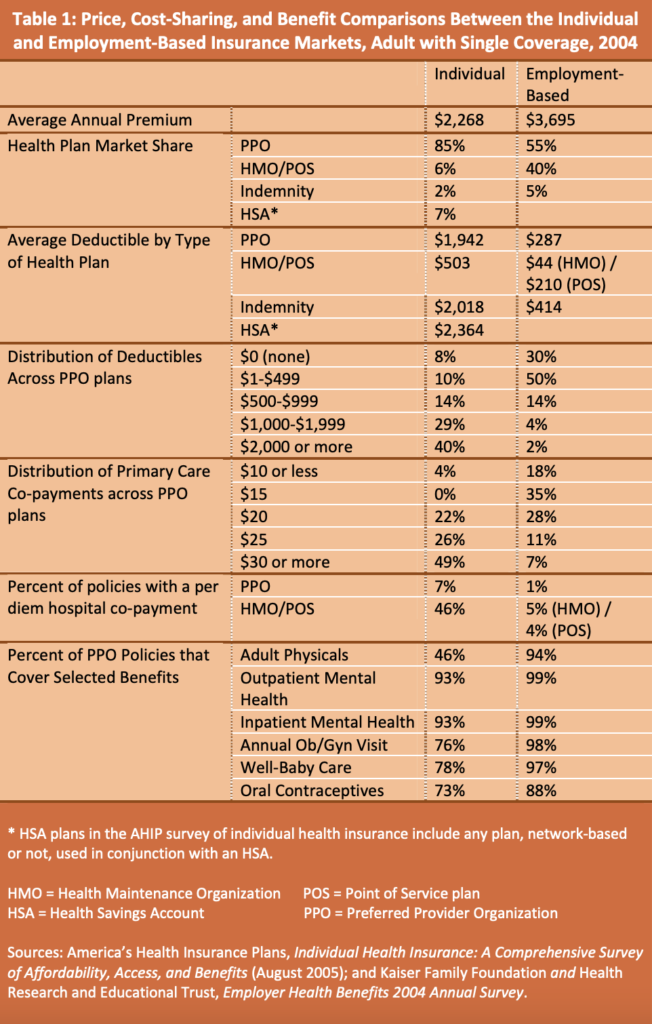

Surveys show that benefits are indeed richer and costs are indeed higher in employment-based health plans. Table 1 compares the 2004 results from two separate surveys studying the characteristics of individual-based and employment-based group health plans and underscores the generosity of employment-based group plans. Because preferred provider organization (PPO) plans dominate both markets, they’re the best representative comparison.

Table 1 shows that fewer individual-market PPO plans cover adult physicals, annual ob/gyn visits, well-baby care, and oral contraceptives. Most individual plans offer to cover these services, but individuals consciously choose not to buy them in favor of paying a lower premium. Thus, people in the individual marketplace are actively tailoring insurance policies to meet their own needs and their own budgets, while those with employer-based plans must take more expensive group plans that meet everyone’s needs.

When people opt out of coverage options, like those listed in Table 1, it does not necessarily mean they will be going without needed medical care. The fact is, some people don’t need certain kinds of coverage, especially coverage options like well-baby care or oral contraceptives. Further, opting out of coverage is often a decision about when to pay. Health insurance is supposed to guard against unexpected health problems, but regular doctor visits — like physicals, annual ob/gyn visits, and well-baby care — are not unexpected and they are relatively inexpensive. Paying for expected medical services through insurance premiums only serves to distribute health expenses evenly throughout the year, which surely can help some people better budget their health expenses, but it requires more costly and administratively complex insurance plans. Some people who prefer lower-cost plans and can budget for occasional visits to doctors’ offices prefer paying for expected services at the times they need them, and thus they opt to not cover them through insurance.

Table 1 also shows that deductibles and co-payments in individual-market PPO plans are far higher than employer-based PPO plans, reflecting the fact that individuals prefer to trade off lower premiums for more cost-sharing. Across individual-market PPOs surveyed, 40 percent of deductibles were over $2,000, and 49 percent of primary care co-payments were $30 or more. Across employment-based plans, only two percent of PPO deductibles were over $2,000, and only seven percent of co-payments were $30 or more.

In light of wider coverage and less cost-sharing, costs are, of course, much higher in employment-based plans. Specifically, the average employer-based annual premium costs 63 percent more than the average plan purchased in the individual health insurance market — $3,695 versus $2,268.

Less cost-sharing in employment-based plans leads people to overuse medical services, which can be costly. Because consumers with employer-based health care don’t directly write checks for their medical bills (and, in fact, rarely know the total bill) and face limited cost-sharing, they have no incentive to economize their use of health care services, which results in higher utilization and higher prices. Harvard University professor Regina Herzlinger explains.

When consumers do not know the cost of things they buy, prices are likely to increase. They may even buy things they do not really want or need because those things appear to be free. Accordingly, hospitals may raise their fees to levels that consumers would not be willing to pay out of their own pockets, while the third party, who actually pays the hospital bills, has no idea whether the user considers the prices too high, too low, or just right. Or consumers may insist on health insurance coverage for items they do not really want or intend to use, simply because they do not pay for the extra coverage. [12]

Indeed, the connection between cost-sharing, medical service use, and medical expenditures has been well documented by studies using data from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. These studies generally have found that, unless a person happens to be sick and poor, more cost-sharing reduces use and expenditures without adverse health consequences. [13]

Fortunately, the recent advent of tax-advantaged Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) and Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs) — savings accounts that consumers can use to pay deductibles, co-payments, and any other medical expense with pretax dollars — have made it easier for employers to develop health plans that require more cost-sharing on the part of employees. Consequently, there is indeed change afoot in the marketplace. Between 2001 and 2005, the average deductible for workers with single coverage (as opposed to family coverage) increased from $239 to $602 in conventional insurance plans. Although a less rapid ascent, deductibles rose from $204 to $323 in preferred provider organization plans, And they rose from $92 to $220 in point-of-service plans. [14]

Nonetheless, cost-sharing in employer-based plans remains markedly lower than the individual market’s standard $2,000 deductible and $25 to $30 co-payments, and it won’t change easily. In Milton Friedman’s words, “Employer financing of medical care has caused the term insurance to acquire a rather different meaning in medicine than in most other contexts.” [15] People now expect health insurance to cover everything. The public’s expectation that “insurance” will pay for routine or easily anticipated medical services — e.g., physicals, dental checkups, chiropractor adjustments, or eyeglasses — makes it difficult for employers to move to lower-cost HSA and HRA options.

Generous health plans force many workers to take a higher proportion of their total compensation in health benefits than they’d like. Employee compensation equals cash wages plus the value of their benefits. Undoubtedly some workers would prefer more wages over benefits, and some would prefer more benefits over wages, but workers generally don’t get to make this choice when it comes to their health plan; workers must accept the cost of the health plan their employer chooses. Health care, then, becomes a fixed proportion of employees’ compensation that they cannot control. For instance, if an employee makes $40,000 per year in cash wages and receives health care benefits chosen by the employer valued at $10,000, at least 20 percent of the total compensation of $50,000 must go toward health care. Restricted from choosing a lower-cost health plan, lower-income workers are then not free to allocate compensation linked to health benefits to some other budget priority, like housing or education.

At the same time, research does show that some workers pick jobs based on the availability of employer-based health benefits and their preference for health benefits, which shows that some workers do exercise a degree of choice over the allocation of wages and health benefits. [16] Nonetheless, once a person chooses a job, and assuming the chosen job offers coverage, the allocation is fixed until the person moves to a new job.

Not incidentally, the fact that people pick their jobs based on their preference for health benefits reveals an entirely separate problem caused by employer-based health benefits. Specifically, employment-based health care seriously distorts the labor market on top of distorting the health care market. While a detailed discussion of labor market distortions is beyond the scope of this report, here’s a sampling of the distortions: sick employees can find themselves locked into their jobs for fear of losing health benefits; employers rely on more temporary workers and outside contractors to avoid paying health benefits, resulting in fewer stable employment opportunities overall; [17] and older workers, who tend to be less healthy, find it more difficult to find jobs in businesses with health benefits. [18]

Generous health plans lead some lower-income workers to turn down coverage and remain uninsured. While not the norm, some health plans offered by employers, especially those offered by smaller businesses, require employees to pay a higher proportion of premiums (often over half the premium), yet the employer still picks an expensive health plan with generous b

enefits. [19] When an employer offers only one plan, and it is a generous plan, and requires employees to cover half the premium, some employees will decide they cannot afford it, turn down the coverage, and choose to remain uninsured. Thus, some low-income workers turn down the portion of their compensation linked to health benefits and get nothing. If employers offered defined cash contributions versus defined health benefits, low-income employees would be in a better position to buy their own insurance. More than likely, the employer half of generous premiums would go a long way toward covering premiums of lower-cost options in the individual insurance market.

Conclusion

Many people point to America’s health care market as proof that free markets simply don’t work for health care. Yet we haven’t had a free market for health care services for decades, ever since employers began providing coverage. Chewing gum companies, refrigerator manufacturers, and job-placement services all rely on market signals sent from millions of purchasing decisions made by millions of unique consumers who either buy or don’t buy their products. This is not the case in the health care market. Health insurance companies must steer their products towards employers: In other words, purchasers, who — even if they could somehow gauge what their employees want — have their own interests, obligations, and incentives.

Free markets do work for health care. But, to be free, the market requires individual-based health plans driven by the needs and wishes of consumers, not employers. Admittedly, health care offers unique challenges not found in most other markets. For instance, a person experiencing a medical emergency is not in a position to shop around. But America’s entrepreneurs are the people best equipped to meet these challenges, not employers or politicians.

Any transition to individual-based coverage will require a Herculean effort. An American population long accustomed to employer-based group plans will not be easily moved. Moreover, any time insurance regulations or insurance markets change, unintended consequences can occur. For instance, if employers were to begin freely moving employees from small group plans to individual plans, individual plans might more readily attract healthy people, leaving disproportionately less-healthy people in their small group plans, which would lead to higher costs for them. However, so long as the individual market is equipped to offer affordable coverage to higher-risk people, such members of increasingly costly small groups will choose to switch to individual plans when prices are right.

High risk people can get affordable individual coverage in various ways. For example, some states already organize high-risk pools that offer affordable state-subsidized private plans to people who have been denied coverage or have been offered only unaffordable options. Alternatively, a state might require (or insurers might voluntarily create) a risk-reallocation payment system that compensates insurance companies that enroll a disproportionate number of high risks. The point is, while transitioning will not be easy, solutions to admittedly tough questions exist.

In the end, the effort will be worth it. Consumers will be more engaged in decisions about their health, making them healthier and at lower costs. Indeed, the latest data on consumer-driven health plans — plans with higher deductibles and more cost-sharing — show that participants are less costly, more engaged in wellness programs, just as likely to get the care they need (including preventive care and care for chronic conditions), and more likely to shop, plan, and save for health care. [20] To satisfy newly engaged consumers, health plans (and providers) will need to become more competitive. Costs will matter more. Quality will matter more. Instead of one-size-fits-all group plans, health plans will need to innovate to meet the needs of individuals, whether they’re diabetics or smokers or health nuts.

To begin moving in the direction of individual-based plans, tax advantages need to be de-linked from employer-paid health care. A uniform tax deduction for individuals, as proposed by President Bush in his 2007 State of the Union address, would be one way. Another would be a refundable tax credit — a tax credit advanced at the beginning of the year for health expenses, where the full value of the credit would be available to taxpayers even if they owe a lesser amount in taxes. Either would be a terrific first step toward transitioning America from employment-based coverage toward individual-based coverage.

Peter Nelson is a Policy Fellow at Center of the American Experiment.

Notes

[1] The Mayo Clinic, “Mayo Clinic Health Policy Center Releases Recommendations to Advance Health Care Reform,” news release, Sept. 14, 2007, available at http://www.mayoclinic.org/news2007-rst/4247.html (accessed Oct 2, 2007).

[2] See Mark V. Pauly, “Taxation, Health Insurance, and Market Failure in the Medical Economy,” Journal of Economic Literature 24, no. 2 (1986): 629-75; and Martin S. Feldstein, “The Welfare Loss of Excess Health Insurance,” The Journal of Political Economy 81, no. 2 (1973): 251-80.

[3] John Sheils and Randall Haught, “The Cost of Tax-Exempt Health Benefits in 2004,” Health Affairs web exclusive (Feb. 25, 2004), available at http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/reprint/hlthaff.w4.106v1.pdf (accessed October 8, 2007).

[4] www.statehealthfacts.org , “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population, States (2005-2006), U.S. (2006),” Kaiser Family Foundation, http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparebar.jsp?ind=125&cat=3 (accessed October 2, 2007).

[5] If the employer group is large enough, employers almost always choose to “self-insure,” meaning the employer takes on the risk and pays their employees’ health bills directly. In this situation, an insurance company is unnecessary because there are more than enough healthy employees to offset employees who might experience a high-cost health problem.

[6] The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, Employee Health Benefits 2007 Annual Survey, available at http://www.kff.org/insurance/7672/ (accessed October 16, 2007).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Andrea Tan, “Creative’s Loss Widens on Competition From IPod, Zune,” Bloomberg News, Aug. 8, 2007, available at http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aS7A4oVMXU7A&refer=home (accessed October 3, 2007).

[9] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employee Tenure in 2006,” news release, Sept. 8, 2006, available at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/tenure.pdf (accessed October 16, 2007).

[10] Jonathan Gruber, “The Incidence of Mandated Maternity Benefits,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 3 (June 1994), pp. 622-41.

[11] HarrisInteractive, “Reputation of Pharmaceutical Companies, While Still Poor, Improves Sharply for Second Year in a Row,” news release, May 5, 2006, available at http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/allnewsbydate.asp?NewsID=1051 (accessed October 3, 2007).

[12] Regina Herzlinger, Market-Driven Healthcare: Who Wins, Who Loses in the Transformation of America’s Largest Service Industry (Perseus Books 1997).

[13] Joseph P. Newhouse, Free for All? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment 339 (Harvard University Press 1996).

[14] Kaiser Family Foundation, Employer Health Benefits 2005 Annual Survey, available at http://www.kff.org/insurance/7315/sections/ehbs05-7-2.cfm (accessed October 5, 2007).

[15] Milton Friedman, “How to Cure Health Care,” The Public Interest, no. 142 (2001): 3-30.

[16] See Craig A. Olson, “Do Workers Accept Lower Wages in Exchange for Health Benefits?” Journal of Labor Economics 20, no.2, pt. 2 (2002): S91-S114; and Alan C. Monheit and Jessica Primoff Vistness, “Health Insurance Availability at the Workplace: How Important are Worker Preferences?” The Journal of Human Resources 34, no. 4 (1999): 770-85.

[17] See Katherine G. Abraham, “Firms’ Use of Outside Contractors: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Labor Economics 14, no. 3. (1996): 394-424; and Garth Mangum, Donald Mayall, and Kristin Nelson, “The Temporary Help Industry: A Response to the Dual Internal Labor Market,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 38, no. 4 (1985): 599-611.

[18] Frank A. Scott, Mark C. Berger, and John E. Garen, “Do Health Insurance and Pension Costs Reduce the Job Opportunities of Older Workers?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48, no. 4 (1995): 775-91.

[19] See Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust (2007). Thirty-seven percent of employees with family health coverage in small firms (1-199 employees) paid over 50 percent of the cost of premiums, whereas only five percent of employees with family health coverage in large firms (200 or more employees) paid over 50 percent of the costs of premiums.

[20] HealthPartners, HealthPartners Consumer Directed Health Plans Analysis (October 2007), available at http://www.healthpartners.com/files/39058.pdf (accessed October 26, 2007); CIGNA, CIGNA Choice Fund Experience Study (October 2007), available at http://cigna.tekgroup.com/images/56/CIGNA_CDHP_Study.pdf (accessed October 26, 2007); and BlueCross BlueShield Association, “Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association Survey Shows Consumer Driven Health Plan Enrollees are Taking More Control of their Healthcare,” news release , Sept. 28, 2007, available at http://www.bcbs.com/news/bchbsa/blue-cross-and-blue-shield-12.html (accessed October 18, 2007).