Why the Anti-Competitive Impact of Minnesota Income Tax Rates is Greater Today than in the 1970s

If you grew up in Minnesota, then you’ve no doubt seen the old Time magazine cover from 1973 touting “The Good Life in Minnesota” with former Gov. Wendell Anderson proudly displaying a freshly caught northern pike. The title of the story was “Minnesota: A State that Works.” This cover story has been used time and again by folks investigating whether Minnesota still stands out as a state that works.

While Minnesota still stands out, I’ve heard plenty of people suggest that Minnesota does not stand out as it once did. Statistics do suggest that Minnesota is regressing toward the mean on a number of measures of the state’s economic and cultural well-being. Of course, the question is “Why are we losing ground?” There are those that look back to our state’s higher tax rates and suggest that maybe we were better off back then because we were more willing to “invest” in public services.

Kevin Winge made this point in a commentary for the Star Tribune last year. He writes:

Minnesotans, 40 years ago [according to Time Magazine] “were willing to elect a man who promised to raise some of their taxes in return for larger overall gains.” Is that just a quaint, outdated notion today, or was it a central reason—along with other societal traits and geographic location—why Minnesota ended up on the cover of Time magazine in 1973 as “A State That Works?” And why we haven’t been back on the cover since.

The implication is that maybe if we go back to those higher tax days, then we can regain some of our former glory. Gov. Mark Dayton certainly seems to think so. After all, he led off the 2011 session with possibly the largest tax increase proposal in the state’s history. The only comparable tax hike on record took place under Gov. Wendell Anderson.

* * *

Without delving into the thorny question of how Minnesota’s tax policy may or may not have contributed to its past successes, data presented in a memo drafted by nonpartisan Minnesota House research staff suggests why going back to higher income tax rates on top earners would pose a far greater challenge to the state’s competitiveness today than in the 1970s.

Lori Sturdevant referenced this memo in a column for the Star Tribune and concluded that it supports both the Dayton and Republican legislature tax positions. As she reported, the memo shows “the effective marginal tax rate paid by those in the top income tax bracket was lower last year than in all but five other years since 1970.” Score one for Dayton—the rich are paying a bit less these days than they have in most of the last 40 years. She further reported that the effective tax rate on Minnesota’s top earners would jump from 43 percent to 53 percent if the Bush tax cuts expire and Dayton’s original tax proposal were to become law. Score one for Republican legislators—wealthy Minnesotans would react strongly to such a sudden tax change.

Overall, her points are accurate, but she did not report the memo’s most important lesson: Top earners have more incentive to move to a lower tax state in 2010 than they did throughout the high-tax decade of the 1970s. Just as important, they have a stronger disincentive to move to Minnesota from a low-tax state today.

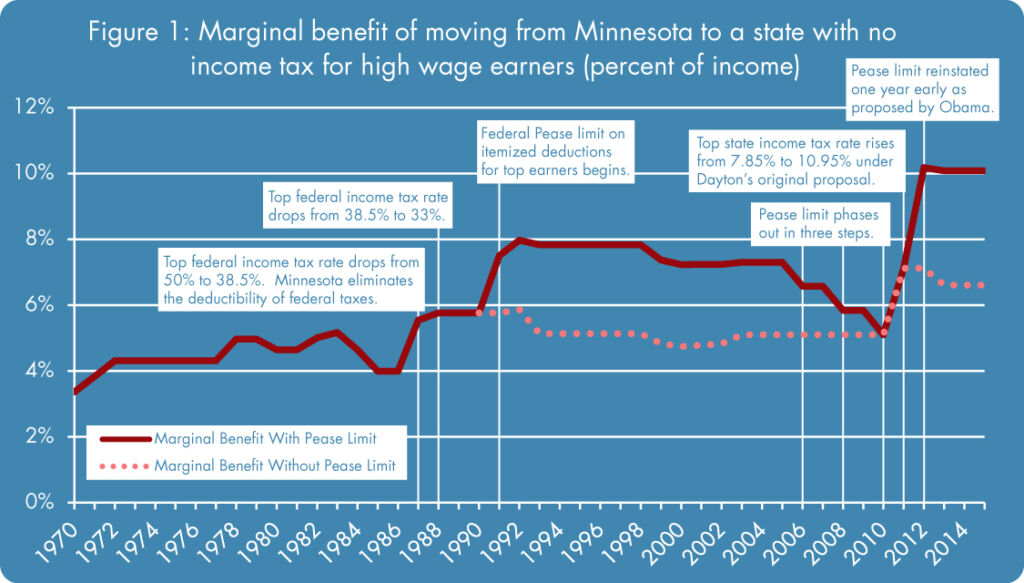

Figure 1 depicts how the incentive for top earners to move away from Minnesota changed between 1970 and 2015 under current and proposed state and federal tax laws. Beyond 2010, the figure presumes the adoption of Dayton’s original tax plan and Obama’s proposal to reinstate the federal Pease limit on itemized deductions a year early (this limit is explained more fully below).

In 2010, a top earner could save 5.10 percent of his or her income by moving to a state with no income tax. By comparison, a top earner in the 1970s had less to gain from leaving Minnesota. The most a taxpayer could save by leaving Minnesota was between 3.36 and 4.97 percent, depending on the year. If the Bush tax cut repealing the Pease limit on itemized deductions expires and Dayton’s original tax plan passes, then a top earner could save 10.08 percent of income by moving out of Minnesota.

* * *

How can this be? How could top-earners have more incentive to leave now when state tax rates in the 1970s ranged from 12 to 17 percent versus a top rate of 7.85 percent today?

The answer lies in the interaction of the state and federal tax code. State income taxes qualify as a federal tax deduction. Until 1986, federal tax payments were deductible in calculating Minnesota state income taxes. The interaction between these two types of deductibility reduced the effective marginal income taxes from the Minnesota state income tax to a small fraction of the statutory rates. The tax benefit to top earners derived from deducting state taxes from far higher federal tax rates in the 1970s in combination with the state deductibility of those federal taxes more than offset today’s lower state tax rates.

In effect, state and federal tax laws moderated the differences in state income tax rates, which allowed Minnesota to have high state income tax rates without creating a huge incentive for top earners to flee the state or a barrier for top-earners to move in. Entrepreneurs were able to build businesses in Minnesota and pass on a substantial portion of the state’s high tax rates to all federal taxpayers through the federal deduction.

Note: Figure 1 depicts changes in the “top state effective marginal tax rate on wage income” between 1970 and 2015. The solid line represents the top state effective marginal tax rate with the full Pease limit on itemized deductions applied and the dotted line represents the top effective marginal tax rate without the Pease limit. Both lines are presented here because most top earners are not subject to the full Pease limit and pay a rate that falls somewhere in-between. The memo reporting this data notes that “[i]n tax year 2008, for example, only about 1,000 of the approximately 140,000 Minnesota returns subject to the limit had their deductions limited to the full extent possible under federal law.” For years 2011 to 2015, the solid line assumes the implementation of the tax rate increases in Dayton’s original 2012-13 biennial budget proposal and Obama’s proposal to reinstate the Pease limit a year early; the dotted line assumes the Pease limit is not reinstated. While the Pease limit is set to be reinstated in 2013 under current law, it is possible that this Bush tax cut will be extended just as Congress has extended other temporary tax cuts.

Source: Nina Manzi to Taxes Conference Committee (H.F. 42/S.F. 27), memorandum regarding federal and state statutory rates and state effective marginal rates on high-income earners, May 2, 2011, Minnesota House of Representatives Research Department.

As Figure 1 shows, that moderating effect began to erode as (1) the federal government cut income tax rates in the 1980s and (2) Minnesota eliminated the deductibility of federal income taxes after 1986. This erosion continued in 1991 when the federal Pease limit took effect and imposed a limit on itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers. Finally, federal income tax rate reductions in the early 2000s also had an impact, albeit a much smaller one. Combined, these tax policy changes substantially reduce Minnesota’s ability to pass its taxes on to the residents of the 38 states with lower marginal income tax rates on top earners.

In 2006, the Pease limit on itemized deductions for top earner’s began to be lifted on a temporary basis as part of the Bush tax cuts. This moderated the impact of Minnesota’s state income taxes because top earners could once again deduct state and local taxes. Nonetheless, the moderating effect is far less than was the case in the 1970s. That’s because federal taxes don’t qualify as a state deduction as they did before 1987. Remember, it was the interaction of the deductibility of both state taxes and federal taxes that moderated those very high 1970s tax rates. It’s highly unlikely that the moderating effect of state and federal tax laws on state income tax rates will ever be as high as they were in the 1970s.

* * *

Ultimately, the main takeaway from the House memo is that state income tax rates matter a whole lot more today than they did in the 1970s. When Minnesota set higher rates in the 1970s, other aspects of the state and federal tax laws offset the anti-competitive pressure of Minnesota’s higher tax rates. That is no longer the case. Tax policy changes in the 1980s and the 1990s reduced the value of state and federal income tax deductions that allowed top earners in the 1970s to offset Minnesota’s high income tax rates. Without that same offset, today’s state income tax rates impose greater pressure on top earners and their employers to avoid Minnesota.

The fact is, we simply can’t go back to the “The Good Life in Minnesota” when other states subsidized our high tax rates. If Minnesota is to move forward with a strong economy, it must replace its 1970s tax system with a pro-growth 21st century tax system that recognizes the enhanced competitive benefits that low tax rates offer today.

Peter Nelson is a Policy Fellow at Center of the American Experiment.