Retiring Worn-Out Wind Turbines Could Cost Billions that Nobody Has

American Experiment has been warning the public about the short useable lifetimes of industrial wind turbines for some time now, but one thing we haven’t really touched on yet is who pays to decommission the turbines once they’re no longer useable?

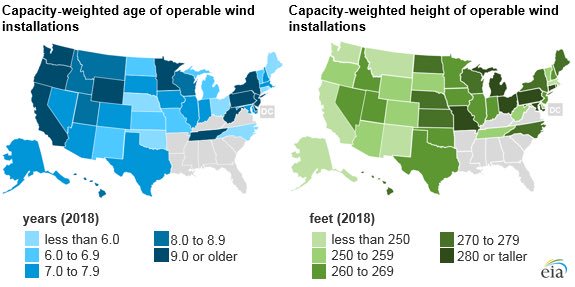

This is going to be a pressing issue in the coming years because Minnesota’s wind fleet is older than the wind fleets in many parts of the country.

The article below discusses the challenges that worn-out wind turbines will present for local governments throughout the country. Who will pay to decommission the turbines if the company’s who owned them go bankrupt?

HARLINGEN – This is a story about death and resurrection, and as with all such stories, faith plays its part.

Texas is by far the leading wind energy producer in the United States, generating more than 20,000 megawatts of electricity each year. That is about one-fourth of the nation’s wind-energy production.

We can expect the Texas winds to blow forever, but the colossal turbines which capture the breeze and transform it into electricity will not turn forever. Like all mechanical things devised by man, no matter how clever, they eventually wear out.

But the question is, what will this mean to the landscape and future of the Rio Grande Valley and, in particular, the counties of Willacy and Cameron?

And here, as we confront the end days of a wind turbine, our story begins.

Deregulating the field

When Texas deregulated its electricity market in 2002, it forced power companies, transmission providers and electricity sellers to separate. For the most part, this has worked well for the state and electricity customers, with the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, known as ERCOT, ramrodding about 75 percent of the state’s efficient power grid.

Deregulation also was a major factor in the rise of wind farms in Texas, with national and even global companies drawn to the state by its Wild West power-generation atmosphere with no regulatory agency, no permitting and no wind laws.

“It’s like prospecting: You can basically go stake your claim and build your project,” Sweetwaterattorney Rod Wetsel, who co-wrote the book “Wind Law,” told MIT Technology Review last fall.

And then, of course, there are the federal subsidies which make wind energy financially possible.

Wind energy production tripled thanks to the Obama administration’s aggressive green energy agenda, going from 8,883 megawatts in 2005 to around 82,183 megawatts today, which is about 5.5 percent of the nation’s total power generation.

The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the total cost to taxpayers of the wind production tax credit between 2016 and 2020 will be $23.7 billion.

Whether those subsidies will continue under the Trump administration remains to be seen.

One big question is how much money is being set aside for the inevitable decommissioning costs associated with removing aging, unprofitable and just plain worn out wind turbines now whirling across the horizons of Cameron and Willacy counties.

Wind turbine: The life and death

The life span of a wind turbine, power companies say, is between 20 and 25 years. But in Europe, with a much longer history of wind power generation, the life of a turbine appears to be somewhat less.

“We don’t know with certainty the life spans of current turbines,” said Lisa Linowes, executive director of WindAction Group, a nonprofit which studies landowner rights and the impact of the wind energy industry. Its funding, according to its website, comes from environmentalists, energy experts and public donations and not the fossil fuel industry.

Linowes said most of the wind turbines operating within the United States have been put in place within the past 10 years. In Texas, most have become operational since 2005.

“So we’re coming in on 10 years of life and we’re seeing blades need to be replaced, cells need to be replaced, so it’s unlikely they’re going to get 20 years out of these turbines,” she said.

Estimates put the tear-down cost of a single modern wind turbine, which can rise from 250 to 500 feet above the ground, at $200,000.

With more than 50,000 wind turbines spinning in the United States, decommissioning costs are estimated at around $10 billion.

In Texas, there are approximately 12,000 turbines operational in the state. Decommissioning these turbines could cost as much as $2.3 billion.

Which means landowners and counties in Texas could be on the hook for tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars if officials determine non-functional wind turbines need to be removed.

Or if that proves to be too costly, as seems likely, some areas of the state could become post-apocalyptic wastelands steepled with teetering and fallen wind turbines, locked in a rigor mortis of obsolescence.

Recycling or resurrecting?

Companies will of course have the option of upgrading those aging wind turbines with new models, a resurrection of sorts. Yet the financial wherewithal to do so may depend on the continuation of federal wind subsidies, which is by no means assured.

Wind farm owners say the recycling value of turbines is significant and recovering valuable material like copper and steel will cover most of the cost of decommissioning.

“The problem is, wind companies have argued vehemently that the cost of money set aside should net out the salvage value of turbines,” Linowes said.

“If it costs $200,000 to take down a turbine, but once you take it down, you strip out the copper, the steel, the resellable components and sell them, then really you can make a profit,” she says of the industry’s pitch.

“So a company will say, ‘So as to cost, subtract that benefit, so rather than $200,000 for a turbine we should only set aside $60,000,’ so there’s a fight over how much money should be set aside,” she said.

In Texas, with virtually no regulatory oversight of wind farms, there is no requirement for wind companies to set aside any funds for decommissioning.

Yet extracting valuable materials from the turbines is not as easy as it sounds. For example, the copper in the wires used to transmit power from the turbine to the grid will have to be stripped of its plastic insulation, a task which would entail serious labor costs.

Also, the sheer size of the steel casings which provide the base of the turbines would take specialized cutting tools to reduce the steel to manageable or transportable chunks.

And the blades themselves are a high-tech wonder of composite material, which most experts agree cannot be separated into its component materials and is thus worthless for recycling.

“The blades are composite, those are not recyclable, those can’t be sold,” Linowes said. “The landfills are going to be filled with blades in a matter of no time.”

Faith in doing the right thing

In Cameron and Willacy counties, the operational wind farms are Cameron Wind, Los Vientos I and II, Magic Valley Wind Farm and the new San Roman Wind Farm. The turbine count for these is approximately 400 operational turbines.

At a cost of $200,000 each, decommissioning these turbines when their working life expires would cost $80 million.

At Duke Energy’sLos Vientos I and II wind farms in Willacy County, there are 191 wind turbines. Across Texas at various locations, Duke has around 900 wind turbines which are operational.

“At each of our wind sites, for example, built into the construction and operational costs is also a plan for decommissioning,” said Tammie McGee, director of corporate communications for Duke.

Duke Energy, which has been in the power business for more than 100 years, is relatively new to the wind industry. McGee said Duke began investing in wind power generation about a decade ago.

She said although Duke hasn’t been around long enough to decommission turbines, plans are in place to “repower” aging wind site locations by upgrading – resurrecting – the equipment.

“What does happen a lot of times, and is happening now around the country, is sometimes instead of decommissioning they will ‘repower’ a site,” she said.

“That involves replacing the turbines on top of the towers with new technology,” McGee added. “In the atowers, too, and put up new and more modern towers.”

If a site is properly located, the winds will still be there, making repowering an attractive financial option since the costs of site selection and development have already been covered.

Most wind farms, which pay landowners on average around $8,000 a year per turbine, have contracts with renewal clauses that stretch out to 50 or 60 years.

If Duke decides to shutter a power plant, including its wind farms, the company is committed to restoring the site to its previous state, she said.

“Regardless of fuel type, whether its gas or coal or wind or solar, once a power plant is no longer in service we restore the land to how it was before we got there,” McGee said.

Calls seeking comment from two other wind energy companies operating in Cameron County, Apex Clean Energy which operates Cameron Wind and Acciona United States, which runs the San Roman Wind Farm near Laguna Vista, were not returned.

Unlike Duke Energy, some of the smaller wind farm companies operating in Texas, with fewer financial resources, may be tempted to just walk away when aging turbines no longer spin a profit.

Linowes believes such moves may begin occurring even before wind turbines outlive their useful life as manufacturing warranties on the big turbines expire.

“At what point does the cost of maintenance tip over to the point it’s not worth maintaining a turbine?” she said. “We’re in something of an unknown or uncertain territory.”

As wind turbine manufacturing has improved, the length of warranties on these products has decreased dramatically and today the terms of most cover between five and 10 years.

It seems paradoxical that warranties would become shorter as products become better, but many wind turbine manufacturers have found a valuable revenue stream in selling extended warranties, similar to companies which sell appliances to consumers.

“It could be a very ugly situation in the next five years when we see turbines need work, and are no longer under warranty and not generating enough electricity to keep running them,” Linowes said.