Taxes have unintended consequences – States with the highest cigarette taxes have the highest rates of smuggling

Last summer, Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton decried cuts in cigarette tax rates. As MPR News reported, “Dayton argues the tax has been an effective tool in discouraging smoking, especially among young people”. Tax something and you get less of it. Or, as he put it in a different context, “Incentives do make a difference”.

Indeed they do. But they might not always incentivize people to act in quite the way policymakers like Gov. Dayton might wish.

High cigarette taxes don’t just make people quit

Not all of Minnesota’s smokers reacted to the tax hikes on cigarettes by quitting. Some people went and bought their smokes in neighboring states. And some people took to smuggling.

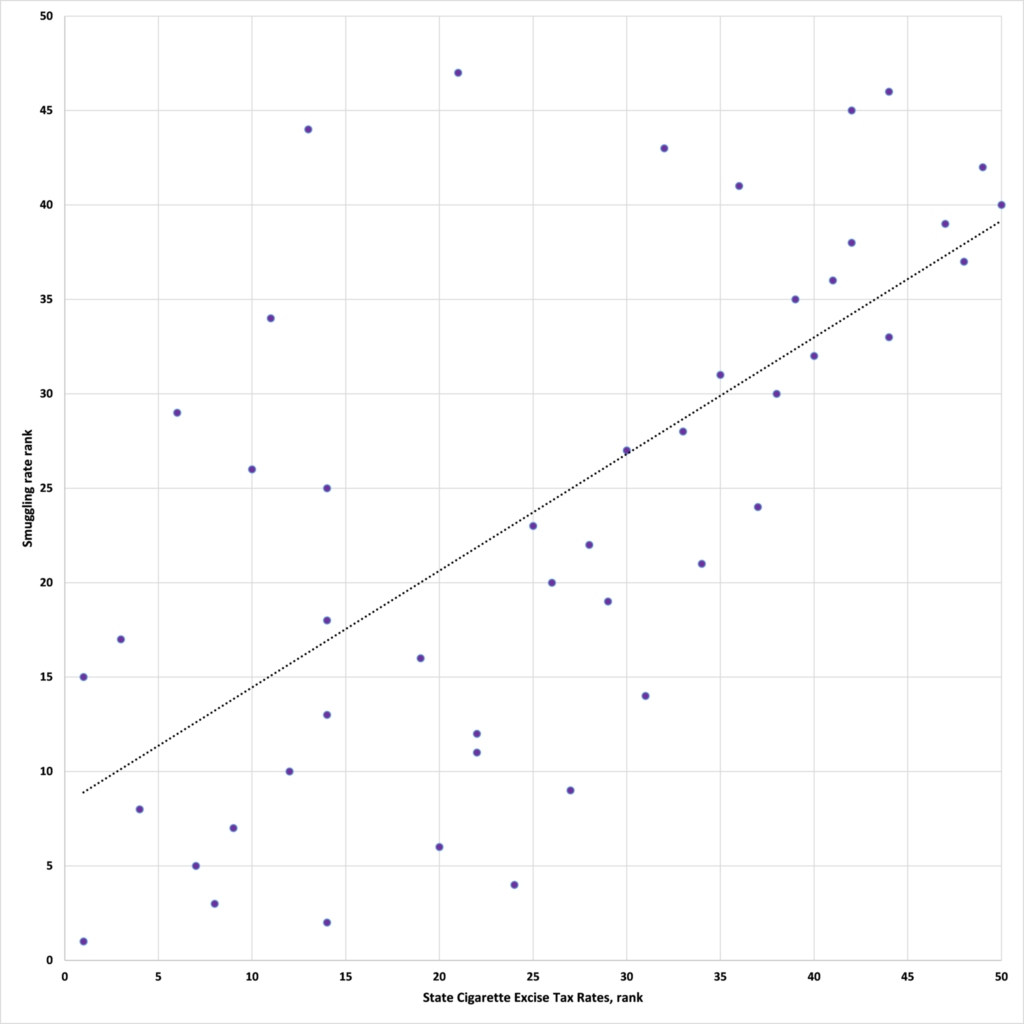

New research by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy finds a ‘Strong Link Between Cigarette Tax and Illegal Smuggling Rates’. This is illustrated in Figure 1. The Tax Foundation ranks each of the states and the District of Columbia by the excise tax levied on a pack of 20 cigarettes, with 1 being the lowest rate and 50 the highest. Mackinac ranks the states by the percentage of cigarettes smoked which are smuggled, with 1 going to the biggest smuggler 50 to the highest. We see quite clearly that as the tax rate on cigarettes goes up so does the amount of smuggling.

Figure 1 – Cigarette tax rates and smuggling by state

Source: The Tax Foundation, the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, and Center of the American Experiment

The Tax Foundation ranks Minnesota seventh in the nation for its cigarette taxes – $3.04 on a pack of twenty. We rank fifth in the nation for the share of cigarettes smoked here which are smuggled in from elsewhere – 35%.

The majority of the consequences of any act are unintended

The point here is not that we shouldn’t be taxing cigarettes, nor, necessarily, that these taxes are too high (although, as an ex-smoker, I wonder how I’d afford the habit these days). The point is that people cannot be relied upon to react as policymakers might wish them to. Politicians might well hike cigarette taxes and some smokers might well quit as a result. Job done. But there are also people who respond differently by shopping around or smuggling.

This applies to things like the estate tax. Politicians might well impose it, they might well raise the rate, and some people might well pay it. But, like those day trippers to South Dakota (the tax avoiders) and those who simply smuggle (the tax evaders), there are those who will respond differently. They might divest of their assets or move. This is not an intended consequence of the policy, but a consequence it certainly is. When appraising a policy, we must look at the unintended consequences, not just the intended ones.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.