The 1619 Project gets it wrong about the American economy

My colleague Katherine Kersten recently wrote a critical reply to the New York Times‘ 1619 Project. This, in case you haven’t heard, “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative”.

Kathy is not alone in criticizing the 1619 Project. Many of the leading scholars in the fields of American slavery and the Civil War – such as Gordon Wood, Allen C. Guelzo, James McPherson, and James Oakes – have strongly criticized it for errors of fact and interpretation.

The 1619 Project and the 19th century American economy

My field is economics. The 1619 Project covered this with an article titled ‘American Capitalism Is Brutal. You Can Trace That to the Plantation‘ by Princeton sociology professor Matthew Desmond.

Here too, the 1619 Project made grave errors of fact and interpretation. I covered some of these in an article for the Foundation for Economic Education, specifically the notions that, first, slavery was equivalent to modern capitalism and, second, that slavery was a source of economic strength, indeed, the foundation for modern America’s wealth.

The first point betrays an almost total ignorance of the true horror of slavery. The second demonstrates a similar ignorance of the reasons for the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War. Simply put, its slave dependent economy was no match for the industrial power of the northern states. As soon as the federal government managed to bring this power to bear on the Confederacy in a sustained manner, it crumbled in fairly short order.

The 1619 Project and the modern American economy

But there is more to criticize in Desmond’s article than just that. His take on modern American capitalism is as wide of the mark as his take on the American economy of the mid-nineteenth century. He writes:

This is a capitalist society…“Low-road capitalism,” the University of Wisconsin-Madison sociologist Joel Rogers has called it. In a capitalist society that goes low, wages are depressed as businesses compete over the price, not the quality, of goods; so-called unskilled workers are typically incentivized through punishments, not promotions; inequality reigns and poverty spreads. In the United States, the richest 1 percent of Americans own 40 percent of the country’s wealth, while a larger share of working-age people (18-65) live in poverty than in any other nation belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (O.E.C.D.).

Or consider worker rights in different capitalist nations. In Iceland, 90 percent of wage and salaried workers belong to trade unions authorized to fight for living wages and fair working conditions. Thirty-four percent of Italian workers are unionized, as are 26 percent of Canadian workers. Only 10 percent of American wage and salaried workers carry union cards. The O.E.C.D. scores nations along a number of indicators, such as how countries regulate temporary work arrangements. Scores run from 5 (“very strict”) to 1 (“very loose”). Brazil scores 4.1 and Thailand, 3.7, signaling toothy regulations on temp work. Further down the list are Norway (3.4), India (2.5) and Japan (1.3). The United States scored 0.3, tied for second to last place with Malaysia. How easy is it to fire workers? Countries like Indonesia (4.1) and Portugal (3) have strong rules about severance pay and reasons for dismissal. Those rules relax somewhat in places like Denmark (2.1) and Mexico (1.9). They virtually disappear in the United States, ranked dead last out of 71 nations with a score of 0.5.

But when we actually examine the data, we find that Desmond’s picture of the American economy as a uniquely awful thing does not hold.

“…wages are depressed…” – Wrong

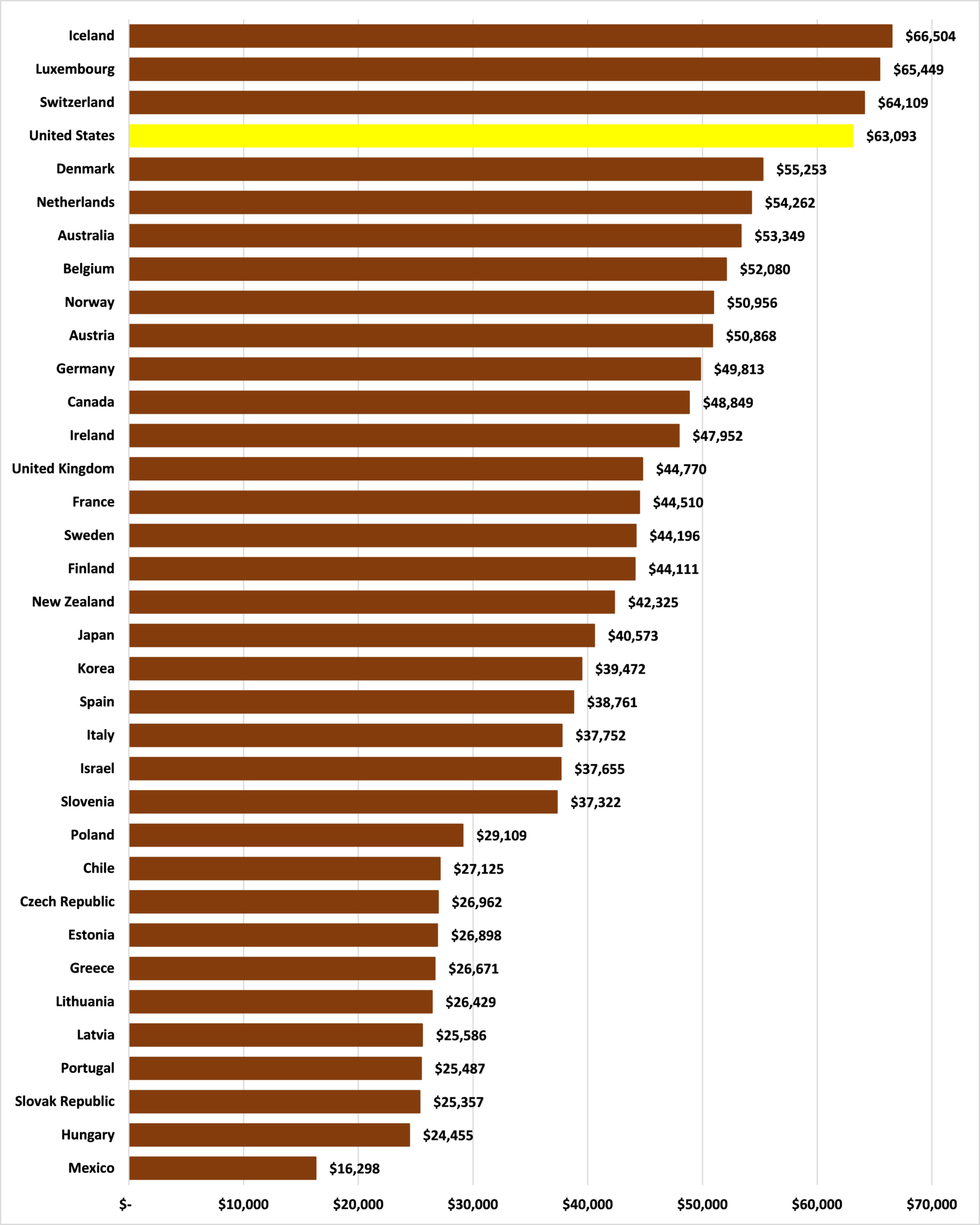

The OECD provides data for Average annual wages, which Desmond doesn’t refer to. Figure 1 shows these for 2018, in 2018 constant prices at 2018 USD Purchasing Power Parities. Out of the 35 countries the OECD lists, the US ranks 4th. Wages do not seem to be especially ‘depressed’ in the US.

Figure 1: Average annual wages, In 2018 constant prices at 2018 USD PPPs, 2018

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

“…businesses compete over the price, not the quality, of goods…” – Wrong

These claims are unsourced. There are few cross-country comparisons of the quality of goods and, as world trade has risen from 27% of global GDP in 1970 to 59% in 2018, it would seem to be less of a concern. Identical goods manufactured in a Chinese factory are likely to be of similar quality whether shipped to the US or Spain.

When it comes to the quality of goods produced in the U.S., a 2017 report by Statistia “surveyed 43,034 people from 52 countries on their perception of products from the various countries of origin”. On the resulting ranking, the US was in 8th place, level with France and Japan, and above Finland, Norway, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, and Spain, all developed countries. Desmond’s perception that US goods are especially low quality would not seem to be shared very widely.

It just isn’t true that producers only compete on price and that price is the only factor consumers take into account. As I wrote recently, if the former is true then why does Mississippi Market exist? If the latter is true then why does anyone ever eat anywhere besides White Castle?

“…unskilled workers are typically incentivized through punishments, not promotions…” – No data

This claim is likewise unsourced. I can find no data on whether unskilled workers in the US are more typically incentivized through punishments rather than promotions, relative to workers in other countries.

To the contrary, research by economists Richard Freeman, Claudio Lucifora, Michele Pellizzari, and Virginie Pérotin, using comparable data on the incidence of performance pay schemes in Europe and the US, finds that the percentage of employees exposed to incentive pay schemes ranges from around 10-15% in some European countries to over 40% in Scandinavian countries and the US.

“In the United States, the richest 1 percent of Americans own 40 percent of the country’s wealth, while a larger share of working-age people (18-65) live in poverty than in any other nation belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (O.E.C.D.)” – True, but so what?

Here, Desmond actually does link to OECD data which shows that he is familiar with the source. This begs the question of why he didn’t link to it in his discussion of wages.

Either way, it is important to note that these OECD numbers are of very limited validity for cross-country comparisons. That is because they measure relative poverty within nations, not between them. As a note on the OECD page explains, the figures show the share of people with less than “half the median household income” in their own nations and thus “two countries with the same poverty rates may differ in terms of the relative income-level of the poor.” You get some idea of how misleading cross-country comparisons using this data can be when you consider the fact that the US (17.8%) has a higher poverty rate than Mexico (16.6%) while World Bank data show that 35% of Mexico’s population lives on less than $5.50 per day, compared to only 2% of people in the US.

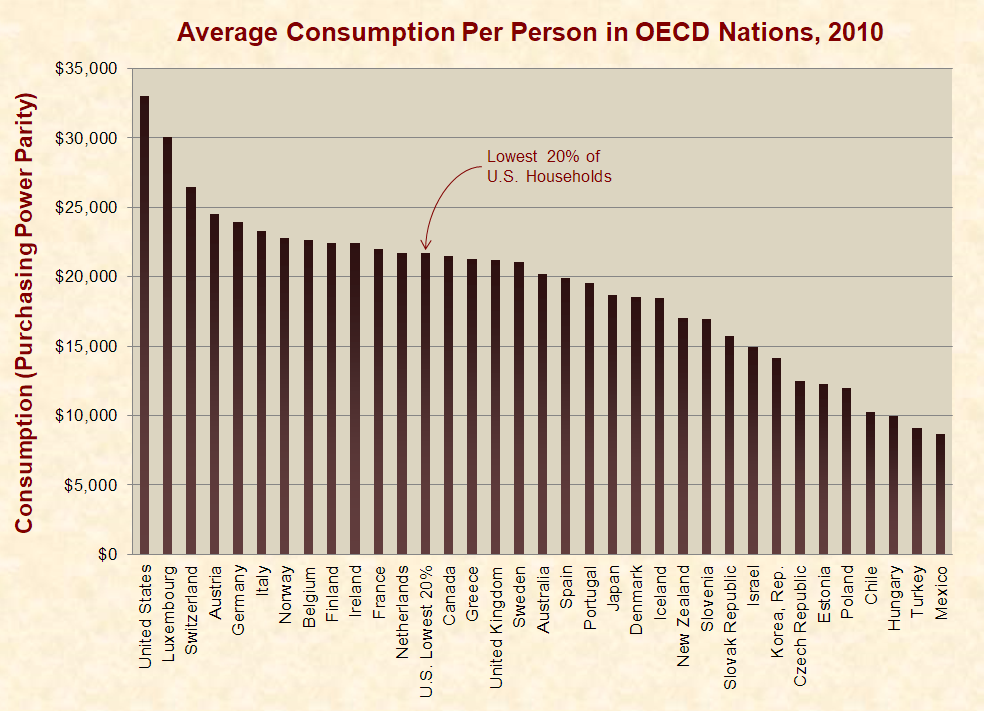

What we need is a direct comparison of the incomes of the poor in the US with the incomes of the poor elsewhere. Fortunately, a recent study by Just Facts provides that. It finds that:

…accounting for all income, charity, and non-cash welfare benefits like subsidized housing and Food Stamps—the poorest 20% of Americans consume more goods and services than the national averages for all people in most affluent countries. This includes the majority of countries in the prestigious Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), including its European members. In other words, if the U.S. “poor” were a nation, it would be one of the world’s richest.

…

This suggests that you are better off being poor in America than averagely well off in Canada or the United Kingdom.

“In Iceland, 90 percent of wage and salaried workers belong to trade unions authorized to fight for living wages and fair working conditions. Thirty-four percent of Italian workers are unionized, as are 26 percent of Canadian workers. Only 10 percent of American wage and salaried workers carry union cards.” – True, but so what?

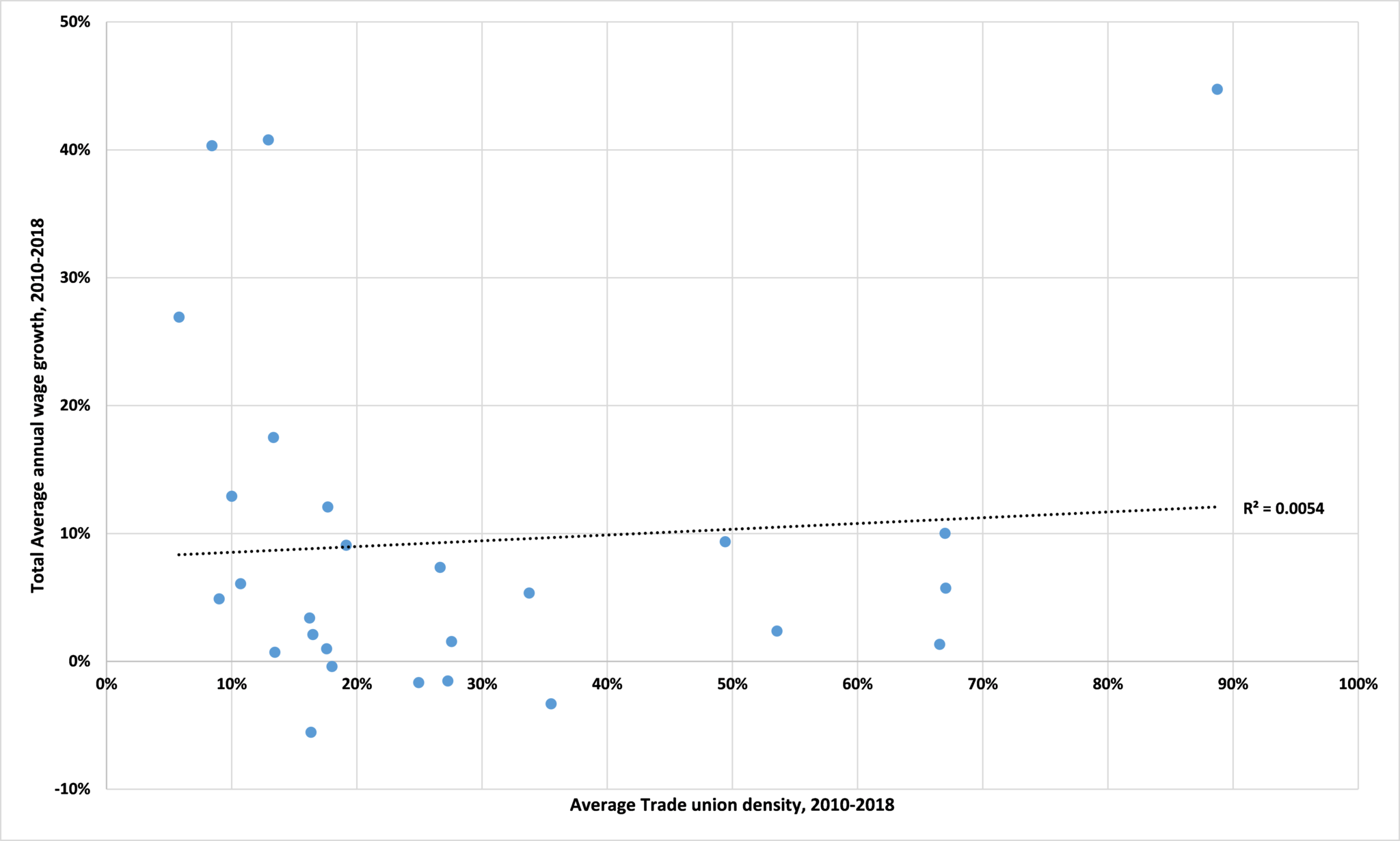

These numbers on Trade union density – again from the OECD – are all correct. But being a union member is a means to an end, not an end in itself. Desmond acknowledges this when he says that unions exist “to fight for living wages and fair working conditions”.

But look again at Figure 1. We see that wages in the US are, on average, much higher than they are in either Canada or Italy, despite the much lower Trade union density here. Indeed, Figure 2 shows the relationship between Average Trade union density between 2010 and 2018 and the total change in Average annual wages – it barely exists. Indeed, what relationship there is is driven entirely by the outlier, Iceland, in the top right corner. Remove that, and the relationship between Average Trade union density and the total change in Average annual wages between 2010 and 2018 actually turns negative.

Figure 2: Average trade union density 2010-2018 and total annual average wage growth 2010-2018

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

With no link between Average Trade union density and the total change in Average annual wages, there is no reason to suppose that the relatively low Average Trade union density in the US is a problem.

“The O.E.C.D. scores nations along a number of indicators, such as how countries regulate temporary work arrangements. Scores run from 5 (“very strict”) to 1 (“very loose”). Brazil scores 4.1 and Thailand, 3.7, signaling toothy regulations on temp work. Further down the list are Norway (3.4), India (2.5) and Japan (1.3). The United States scored 0.3, tied for second to last place with Malaysia. How easy is it to fire workers? Countries like Indonesia (4.1) and Portugal (3) have strong rules about severance pay and reasons for dismissal. Those rules relax somewhat in places like Denmark (2.1) and Mexico (1.9). They virtually disappear in the United States, ranked dead last out of 71 nations with a score of 0.5.” – True, but so what?

Much the same as the above applies to this point.

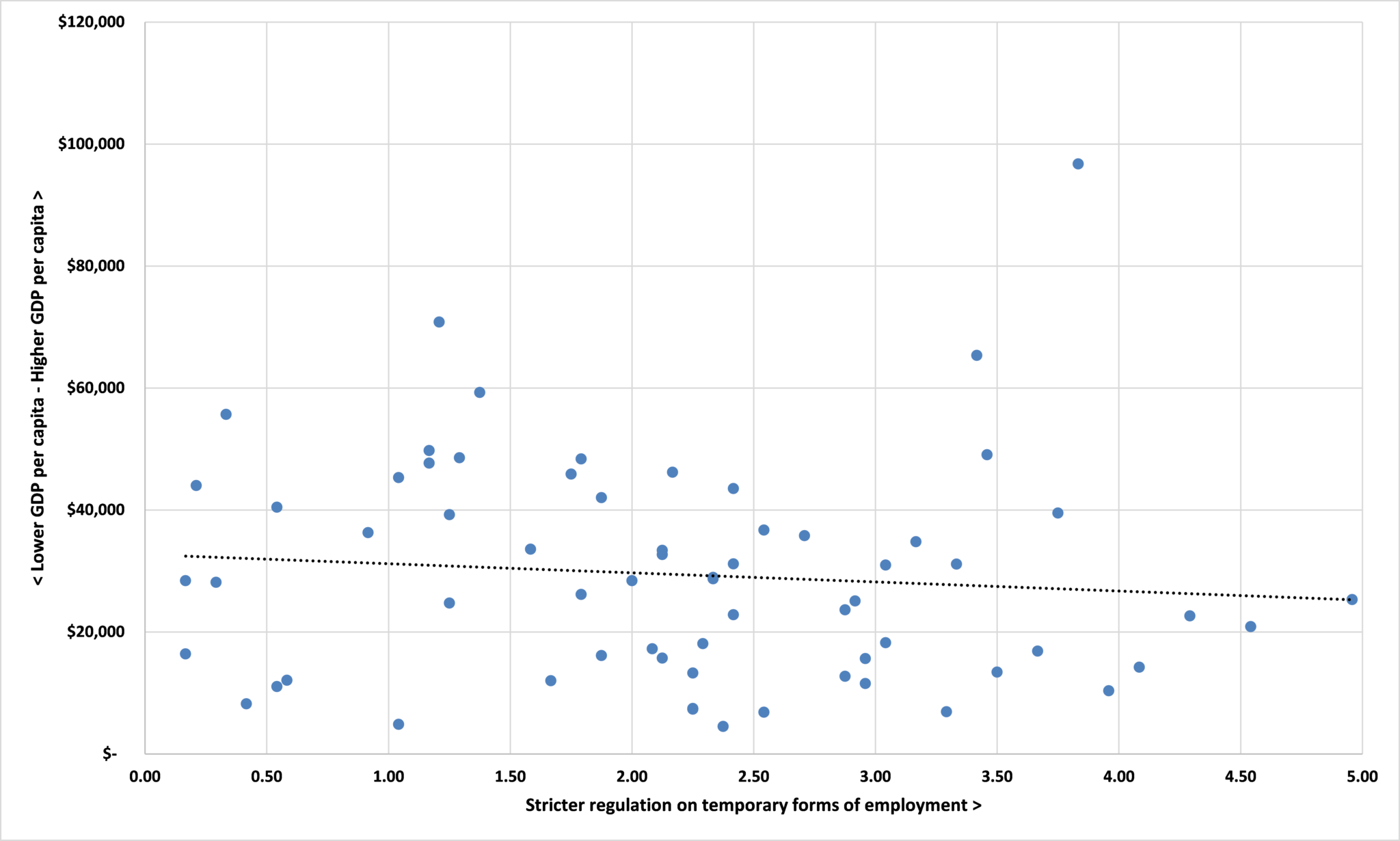

It is true that on OECD Indicators of Employment Protection the US scores as relatively unprotected (thought it worth pointing out that these all relate to years between 2012 and 2015). But do we in the US, where, according to the World Bank, GDP per capita was $55,719 in 2018, really want the economy of Brazil, where it was $14,283? Or Thailand, where it was $16,905? Indeed, as Figure 3 shows, stricter regulation of temporary work arrangements, as measured by the OECD, aren’t correlated with higher per capita incomes as given by the World Bank.

Figure 3: Strength of regulation on temporary forms of employment and GDP per capita

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and World Bank

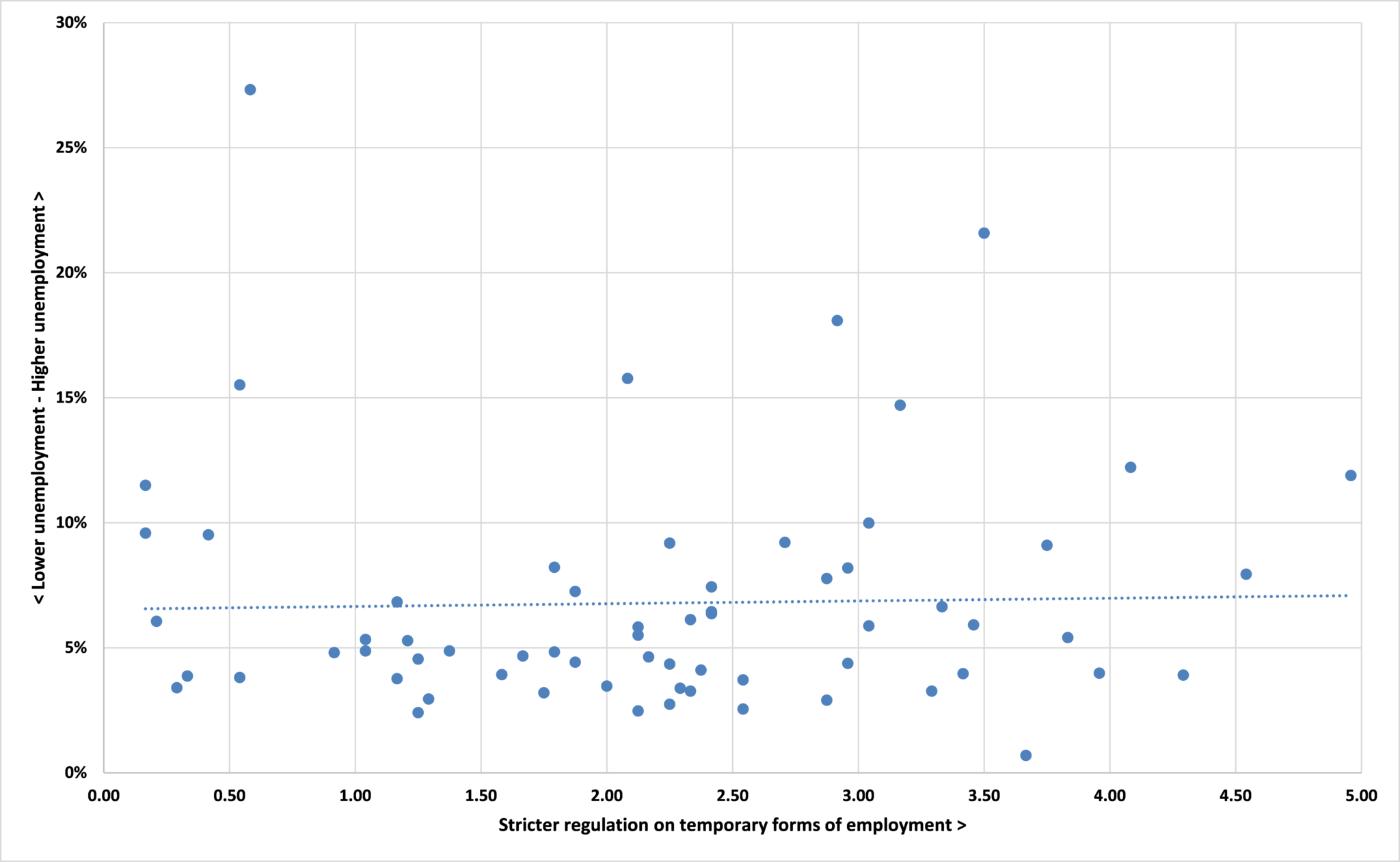

Ah, but doesn’t this lack of protection employment protection lead to loads of unemployed workers? Figure 4 suggests not. Again, there appears to be no correlation between stricter regulation of temporary work arrangements and the unemployment rate. Again, would we want the US – where the unemployment rate is 3.9% – to swap places with Portugal, where it is harder to fire workers but the unemployment rate is 6.1%?

Figure 4: Strength of regulation on temporary forms of employment and unemployment rate

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and World Bank

So, while the US does have fewer regulations relating to employment, it isn’t clear that Americans are losing very much from their absence.

The bottom line

In his essay for the 1619 Project, Matthew Desmond paints a bleak picture of the American economy. The trouble is that the evidence just doesn’t support his case. Phil Magness has made the case for retracting Desmond’s essay. I haven’t read the other essays in the collection, but, whatever their merits or otherwise, they will only be harmed by their association with this piece.