The biggest battle in American history started 100 years ago today

Even today in Britain it can be difficult to avoid reminders of the First World War. The smallest villages have a memorial to the local boys and men who died between 1914 and 1918. As a kid, I remember the pubs closing for a few hours in the afternoon under legislation passed in the wake of the battle of Loos in 1915. And to this day, the hymn Abide With Me is sung before the FA Cup final, a tradition started in 1927 in memory of the men who didn’t return.

It is not the same here in the United States. I moved here in 2017, the centenary of the U.S. entering World War One, but, aside from a very good exhibition at the Minnesota History Center, little seems to have been made of it. Compared to the Civil War, World War Two, or even Vietnam, it feels like America’s forgotten war.

The U.S. in the First World War

The U.S. entered the war in April 1917. With its vast supplies of wealth, industry, and manpower, this represented a huge boost for the Allies (mainly Britain, France, Russia, and Italy) and blow for the Central Powers (mainly Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey). But in early 1917, the U.S. was woefully unprepared for warfare on this scale. Its army numbered about 200,000 – a drop in the ocean compared to Britain’s 2 million – and it was trained and equipped for pacifying Native American tribes and guarding the volatile Mexican border. It would take time to train and equip these troops, not to mention the vast numbers of conscripts, for the fighting on the Western Front. An often bitter dispute would develop, lasting for the rest of the war, between the U.S. and the Allied leaders who wanted American soldiers in France and Belgium as soon as possible.

Draftees leaving Kanabec County Court House, September 22nd, 1917

In November 1917, the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia and began peace negotiations with Germany. The German High Command saw a window of opportunity. With the Eastern Front closing down, they would have the chance to switch troops to the Western Front where, with a great offensive, they could win the war in early 1918 before American troops arrived in overwhelming numbers. Opening on March 21st, 1918, the German Spring Offensives battered first the British and then the French, pushing them back and inflicting horrific casualties, 288,000 French and 225,000 British between March and the end of June. But the Germans also suffered. Between March and June, the German army suffered an estimated 688,000 casualties. Worse still, included in this butcher’s bill were almost all of Germany’s crack Stormtroopers. In July, the final German offensive of the war failed utterly. The window of opportunity had slammed shut.

It was now time for the Allies to go over to the offensive and the American army would play a leading role. The Western Front still formed a rough L shape with its point towards Paris. The Allied Generalissimo, the Frenchman Ferdinand Foch, conceived a vast pincer movement on the German lines. The British under Field Marshal Haig, with support from the French and U.S. II Corps, would drive east from their positions between Cambrai and St. Quentin into the vertical arm of the L. The Americans, under General Pershing, again with French support, would drive north into the horizontal arm of the L in an area flanked by the Argonne forest on the left and the river Meuse on the right. The date of the attack was set for September 26th, 1918.

The battle of the Meuse-Argonne

That morning 600,000 Doughboys of the U.S. First and Second Armies were poised to go into battle. Unlike the flat swamps of Flanders or the rolling hills of the Somme, the area between the Meuse and Argonne was made up of steep, thickly wooded hills. Even worse, these hills formed ridges running parallel with the American starting positions meaning that each one would be a battle in itself to take and hold. The defenders here had every advantage nature could give them.

U.S. Marines during the offensive

Lieutenant Francis Scott ‘Bud’ Bradford Jr., a Wisconsin native of the U.S. Army’s Company H, 39th Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division, left this description of the opening of the battle of Meuse-Argonne.

We moved into the trenches on the famous hills about Verdun. The ground was plowed in a sickening churn. Not a blade of grass remained. We dug in, for the trenches were in poor repair. We dug but not dirt alone—legs, arms, skulls, helmets, all the debris of the mighty struggle.

By 2 a.m. we were ready. A half hour’s tense wait. At 2:30 the barrage cut loose. For three hours a solid sheet of flame lit up all behind us.

O God, O God, the poor devils on the other end.

At 8:30 we went over, a link in the grand attack. Another battalion was in the lead. About 10 the first morning prisoners commenced to come in. They were an inspiring sight, to say the least. Shells were breaking through us, and every now and then machine guns flattened us to the ground, but we kept on without losses until the evening of the first day. We were lying in what had once been a town when five Boche planes swooped over us and dropped bombs into the company, killing two men and wounding a third.

For two days we chased the Germans across five miles of devastated territory, through rain and mud and hunger. Now we moved steadily forward, now we were held up, now we were exploring enemy works, now digging in against counterattack. The evening of the second day the battle lagged. Our artillery could not keep pace with us. The resistance was stiffening.

The next morning the 2nd Battalion was shot in, to swing the balance. There was the long advance; the acrid odor of the gas; the beautiful little puff balls in the air above your head, thick as cotton in the field; the continuous whine of the bullets; the industrious grinding of the Marines landing us iron rations by the box; and above all the terrible cries from some familiar form wrenching beside you in his blood or unseen among the weeds.

You wonder how you have gotten so far—where in hell is that other combat group? You feel under your skin that you are the one man in the world who can look on wounds and death as something that will never come your way—“In the name of the Lord, where are we?”—you curse for just one German to take apart piece by piece and then feed to the animals.

H Company went into the first lines with a smash. By nine we had advanced two kilo[meter]s under terrific shrapnel, high explosive, and machine gun fire mixed plentifully with gas….I can hear those bullets yet! I put on my [gas] mask. Inside of five minutes I had completely lost my bearings. We took off our gas masks and got through somehow.

We passed a high railroad before I realized that I was way in the lead of the regiment. Just at that moment a German machine gun opened on our right flank and another in our front, at 700 yards. To charge them across the open would have been suicide; to stay where we were on the nose of the hill, worse. We were partly concealed in brown weeds about a foot high.

I didn’t pull any hero stuff. I ordered a withdrawal 100 paces to the railroad track to reorganize. We started, but just then the Boche artillery got our range and the heavens opened. Machine gun bullets were coming as thick as holes in player piano [music rolls]. One got me in the right foot. I turned to [First Sergeant Emil] Dallman and said, “Get the men back; I’m hit.” Then all the bells in the land broke loose—I grabbed my head with my hand; blood poured down my face and blinded me. I lay there for several moments betting on whether I was dead or alive.

A bullet had gone through the middle of my tin derby. After I got the blood from my eyes, I wrote the captain a message of our predicament and turned to the runner on my left. He was sure hugging the ground. I hit him with a stone. He didn’t move. He was dead. I turned to the man on my right. He was lying on his side and I saw him hit twice more.

Then I realized I was all alone. I got to my knees and started [crawling] for the track. The snakes commenced to creep in the grass again. Bees droned and sang overhead. I finally made the railroad. When I got in after my weird crawl [the other men] were sure a surprised bunch. Saw the hole in my helmet and thought I was dead.

Back behind the railroad [track] we clung for three hours. Then the infantry went on for a kilometer jump. And there I was with one other man getting the shell fire meant for that infantry line. A four-by-one-half-inch piece of the next shell struck the webbing where his pack strap crossed his shoulder and turned him over twice before he hit the ground. I’d gotten so used to dead men, I didn’t even ask if he were killed—nor glance his way. However, the piece hadn’t even penetrated.

I lay five mortal hours behind that bank while the Boche searched it with his artillery. About 3 in the p.m. I sighted an “ambulance” borne between two [stretcher-bearers] that came strolling over the rise. Going back was wonderful. It was so nice to think of all the work I wasn’t doing.

The backward trail was interesting. There was a battery of German guns, weirdly disarrayed; there was a battery of 75s on a bare slope firing with clocklike precision. It was beautiful. There was a plentiful sprinkling of smoldering aeroplanes, there were the supplies of the mighty army moving forward, there were the wounded and the dead, but always flowing forward as far as the eye could see the Infantry, the Infantry!

It made my chest swell and I thought, “Gosh, I was in the lead of all this!”

Now our army is no different in general respects from any other army: You always find cowards sneaking to the rear on some trivial excuse. Shell shock and gas have become the bluffs[, so] you have to have a pretty good dose of either to get admitted.

One young doctor at the field hospital, whose apparent business it was to ferret out these cases, came down the line in the most approved military manner.

“And what’s the matter with you, buddy?” he demanded of a captain sitting on a stretcher next to mine.

“Well, I guess I’ve got a little gas.”

“Yes, you have. Don’t try to pull that bluff. There wasn’t any gas shot today.”

I lay in the field hospital two days on the ground under fire, got tired of it, crawled to the road, and got a lift to an evacuation hospital, then to a base.

The bullet in my foot did not break a bone. It went in midway between toe and heel half an inch up and out the bottom. My helmet deflected the other [bullet] over my left ear, from whence it dropped to the ground, giving me only a scalp wound. Am going to send that helmet home!

I am in excellent shape, absolutely no pain and the happiest man in the hospital.

The Americans grappled with the Germans in the Meuse-Argonne until the last day of the war, November 11th, 1918, heaving them out of one formidable defensive position after another. They might not have achieved the breakthrough that Foch had envisioned, but they had pinned down large numbers of troops which the German High Command could not move north to reinforce their crumbling positions in front of the British. The men who fought at Meuse-Argonne played a key role in winning the war on the Western Front in 1918. But at a cost. The American army had suffered more than 120,000 casualties in this battle, including 26,277 dead.

Meuse-Argonne, 100 years on

The Meuse-Argonne offensive was the biggest battle in American history. Yet, it seems to me a largely forgotten one. The French author Roland Dorgelès, himself a veteran of the trenches of the First World War, wrote

We will forget. Mourning veils, like autumn leaves, will fall. The image of the dead soldier will slowly disappear from the comforted heart of his loved ones. All the dead will die for a second time.

Only if we let them.

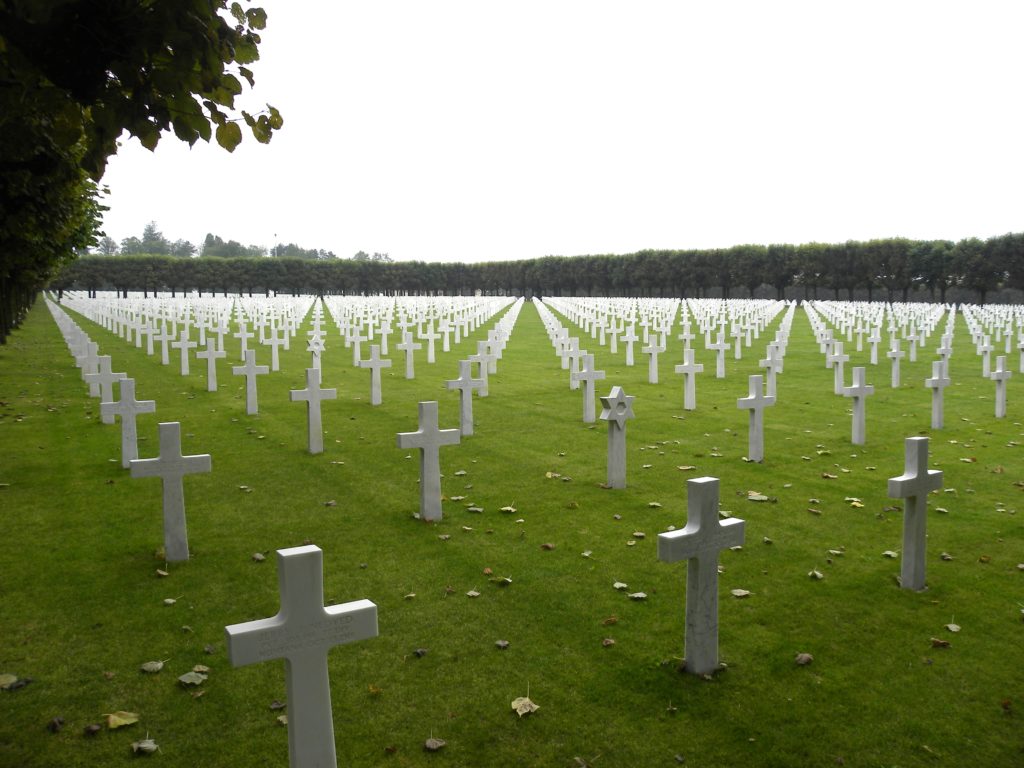

The Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.