The Met Council: The Least Safe Operator of Its Peers

In the last two weeks, our ever-expanding Metropolitan Council announced that it intends to become the owner of a rail corridor in order to facilitate the construction and operation of the Southwest Light Rail line (SWLRT), which would be an extension of the current Green Line. Specifically for the new line the Council would own the rail corridor and operate light rail trains adjacent to freight trains.

In the last two weeks, our ever-expanding Metropolitan Council announced that it intends to become the owner of a rail corridor in order to facilitate the construction and operation of the Southwest Light Rail line (SWLRT), which would be an extension of the current Green Line. Specifically for the new line the Council would own the rail corridor and operate light rail trains adjacent to freight trains.

It seems no task is too big for our uniquely unelected regional authority, which has by far the largest budget and scope of any such organization in the country. So where would that leave us?

Is the proposed SWLRT a good use of taxpayer funds? No.

Is the proposed route one that serves a densely populated area, with many potential riders? No, not even the Met Council pretends that is true.

In light of the most recent developments, legislators and others are asking, is the Met Council even qualified to safely operate both freight and passenger light rail trains adjacent to each other? The data suggest the answer is no.

Let’s start by stipulating that the Met Council believes there is not a safety concern with running both freight and light rail down the same corridor. In fact, as reported in the Star Tribune:

“Many LRT systems in the U.S. operate in shared corridors with freight rail including Dallas, New Jersey, Denver, [Los Angeles], Sacramento, St. Louis, Charlotte, Portland, and San Jose.”

Of course, the question here is not whether or not other systems can do this safely, but whether or not the Met Council can do so safely.

Fortunately we can start to answer that question with data from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Transportation Database. The NTD Safety & Security Time Series compiles data on light rail system incidents such as overall Events (property damage over $25,000, injuries, derailments, etc.), and separate breakouts for Collisions, Injuries and Fatalities.

The database also includes data on various factors related to how active the system is, such as Train Revenue Miles. This measures “the number of miles traveled by whole train vehicles in revenue service.” In other words, if a 3-car train carries paying passengers 10 miles, it generates 10 Train Revenue Miles. This unit of measure is similar to Train Miles, which is what the federal government uses to calculate safety for freight trains, and it is what we’ll use for our calculations on light rail safety.

Recall that the Met Council defined a peer group of cities that already operate freight and light rail in the same corridor – something the Met Council does not yet do. So how does our vaunted Met Council compare? Well, since the opening of the Green Line light rail line, it has consistently been one of, if not the LEAST SAFE of any of those peer systems.

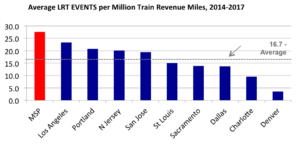

Since 2014 the Met Council has averaged 65% more “events” than its self-described peer group, and it has clearly been the worst performer.

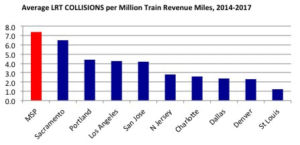

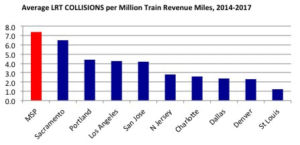

Since the opening of the Green Line, the Met Council has average nearly twice as many collisions as the peer group average, and it has again been the worst performer of the group.

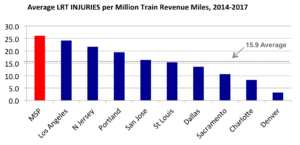

And in terms of injuries, the Met Council once again leads the pack in a dubious way, with an injury rate nearly 50% higherthan the peer group average.

Data for all charts from The National Transportation Database. As of 28 March 2018, data for 2017 was only available online through November 2017. Final figures for 2017 were extrapolated to provide an estimate for the entire year.

It seems the local freight railroads have picked up on this safety issue, as they’ve made numerous related demands of the Met Council. The Burlington Northern and Santa FE (BNSF) required a $20 million “Crash Wall” between its track and the proposed Green Line west of downtown Minneapolis. The BNSF also required the Met Council to provide it a $295 million Railroad Liability Policy to protect against what seems to be the inevitable incident between a freight train and a Green Line passenger train. Incredibly, the BNSF agreement even requires the Met Council to lead any response to legal challenges to this agreement that are raised by local units of government. In other words, the Met Council would defend a corporation against the very citizens the Council allegedly represents.

The Met Council is unique in many (awful) ways. The data show the Met Council runs the least safe light rail system in its peer group, and local freight train operators have clearly caught onto that fact.

What more evidence do we need to #StoptheRunawayTrain?