Star Tribune embraces report that largely repeats what American Experiment has been saying for years

The Minnesota Chamber has a new report out: “Minnesota: 2030, a framework for economic growth.” It is a weighty tome, but this does mean that it contains a lot of information. For those interested in the state’s economy, it is well worth reading.

Much of it will be familiar to those who read our annual economy reports. The Star Tribune notes:

“Minnesota 2030: A framework for economic growth” displays an impressive breadth of research, with the type of private-sector analysis missing for too long in this state. It provides an unflinching analysis that demonstrates how the state’s many strengths have lulled some into a false sense of security, masking serious weaknesses.

In my time at Center of the American Experiment, I have authored reports titled “The State of Minnesota’s Economy: 2017: Performance continues to be lackluster,” “The State of Minnesota’s Economy: 2018; Minnesota’s economic growth continues to be unimpressive,” “The State of Minnesota’s Economy, 2019: Economic growth continues to lag,” and, last month, “The State of Minnesota’s Economy: 2020: A focus on economic growth.”

The Star Tribune reports:

For instance, despite its many advantages, when comparing growth “Minnesota’s economy has been trailing its peers and the U.S. economy the past two decades. GDP and job growth ranked 36th and 45th nationally in 2019,” the report said.

On GDP growth, we noted in our 2019 economy report that:

While Minnesota’s level of GDP per capita compares favorably with the national average, that has not been the case in recent years for its growth rate of GDP.

…

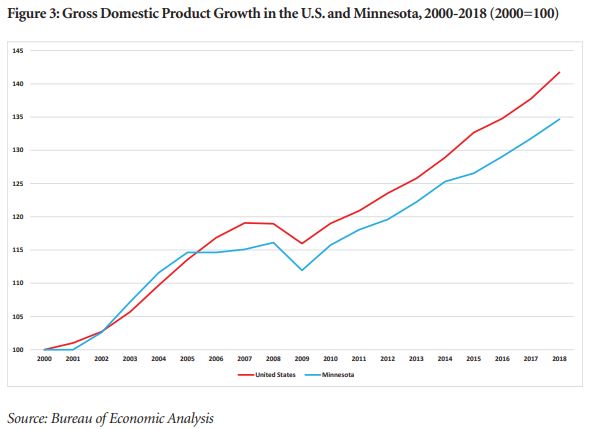

As shown in Figure 3, Minnesota’s GDP growth more or less matched that of the United States generally between 2000 and 2005. After that, they diverged. Minnesota’s output remained more or less flat from about 2005 to 2008. Then the recession struck, which impacted our state slightly more than the nation as a whole. Since then, Minnesota’s growth has matched the national average. It has not regained any of the relative ground it lost in the mid-2000s. Overall, in 2018, the United States’ economy was 41.7 percent larger in real terms than it was in 2000 while Minnesota’s economy was 34.7 percent larger. If Minnesota’s economic growth rate had matched that of the nation since 2000, the state’s GDP would have been 5.2 percent higher in 2018 than it actually was.

(Our 2020 report updated this but primarily focused on per capita numbers and I noted our below average GDP growth for 2019 a year ago this coming Saturday.)

On job growth, our 2019 report noted:

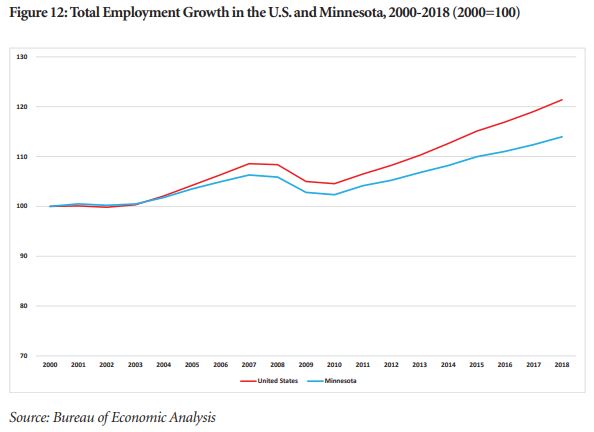

As Figure 12 shows, Minnesota’s job growth has lagged that of the nation as a whole since 2000. Since the turn of the century, employment across the U.S. has grown by 21.4 percent but by just 14 percent in Minnesota. This ranks our state 32nd out of the 50 states and District of Columbia over the period.

But the Star Tribune is the Star Tribune. It goes on:

Those who reflexively blame tax rates should look far deeper and wider. An aging population, lack of in-migration from other states, a brain drain of students who go outside of Minnesota for colleges elsewhere and too often don’t come back, and underutilized populations in both rural areas and communities of color have all combined to take a toll. The worker shortage, the report found, is now a primary constraint on Minnesota’s economy.

We actually did a whole report on the “worker shortage” back in 2019: “Minnesota’s Workforce to 2050.” This discussed the state’s aging population in depth, but also noted that this is not a problem specific to Minnesota and that our state isn’t one of the worst impacted.

About the “lack of in-migration from other states,” my colleague Peter Nelson noted in our report “Minnesotans on the Move to Lower Tax States 2016“:

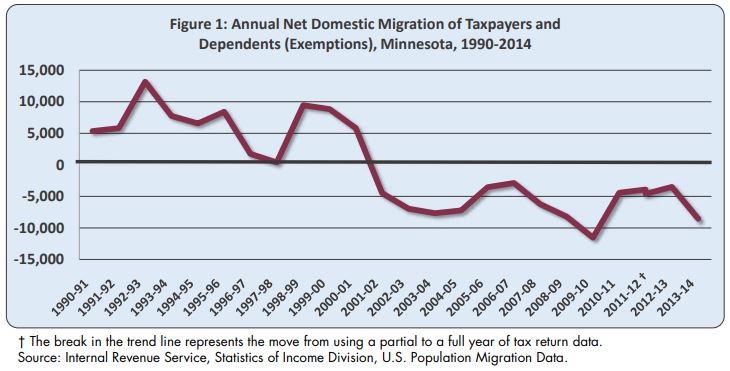

As shown in Figure 1, the net domestic migration of people (taxpayers and their dependents) into Minnesota turned negative in 2002 and has remained negative ever since.

About the “brain drain of students,” we noted in our 2018 economy report that:

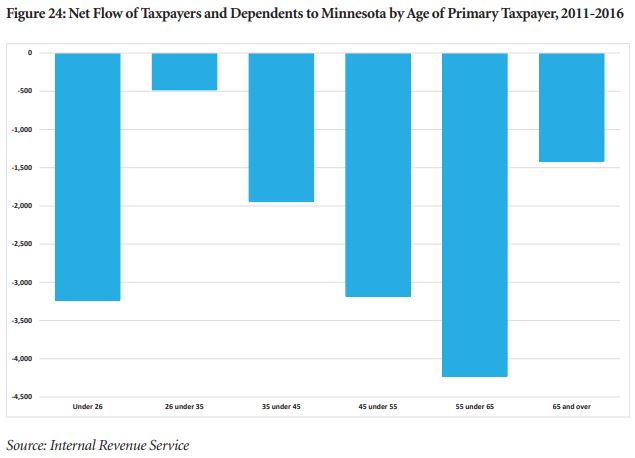

A common misconception is that this out-migration is primarily accounted for by “snow birds,” older Minnesotans leaving the state for friendlier climates. This is not the case. As Figure 24 shows, between 2011 and 2016 Minnesota lost residents in every age group. Those less than 26 years old saw the second largest net loss after those aged 55 to 65. People aged 45 to 54 — people in the prime of their working lives — also made up a substantial share of the loss.

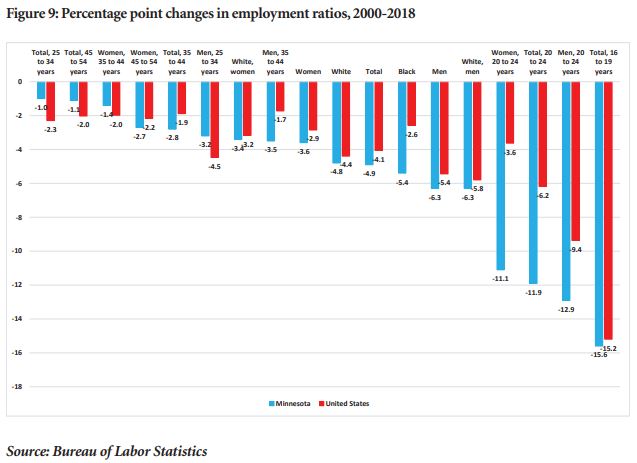

And on “underutilized populations,” our 2019 report on Minnesota’s workforce noted that, between 2000 and 2018, the employment ratio for black Minnesotans fell by 5.4 percentage points compared to a fall of 2.6 percentage points nationally. We noted that:

…if Minnesota’s employment ratio for its black or African American residents could be returned to its 2000 level, there would be a further 13,832 in employment.

The Star Tribune also notes that:

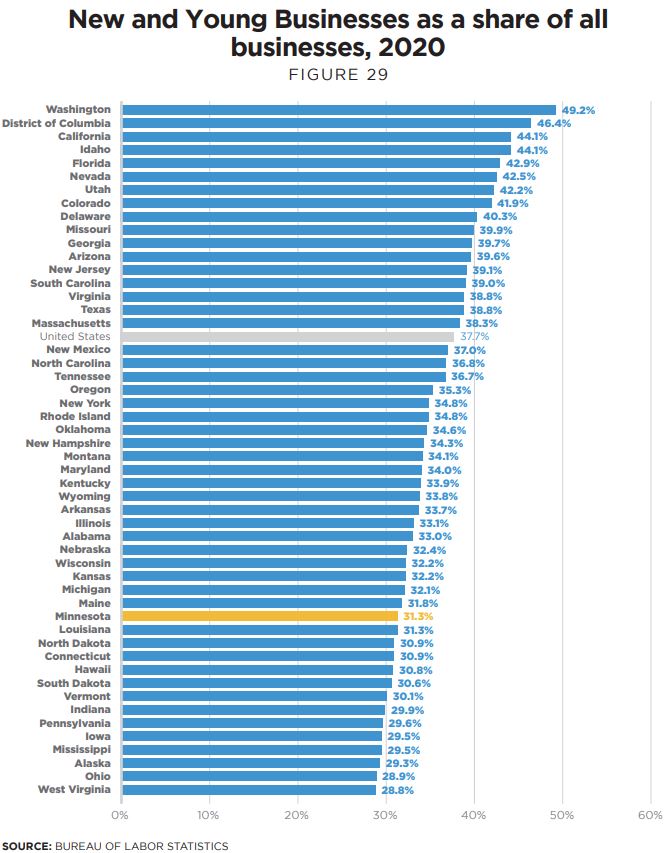

The state also ranks 49th in entrepreneurship and small-business startups.

This will be old news to readers of our 2020 economy report, which noted that:

Figure 29 shows that, in 2020, New and Young Businesses — those which are five years old or less — accounted for just 31.3 percent of all businesses in our state. For the United States generally, the figure was 37.7 percent and Minnesota ranked 38th.

The Star Tribune generally paid little attention to these reports. It isn’t that this “analysis [has been] missing for too long in this state,” it is simply that the Strib has ignored it.

Why? Perhaps they give the game away when they mention “those who reflexively blame tax rates.” Judging by its endorsements, the Star Tribune likes the state’s high taxes. But, what, then, does it think is causing all the symptoms it bemoans? Because the “lack of in-migration from other states,” the “brain drain of students,” the under-utilization of workers, and the lack of entrepreneurship and small-business startups in Minnesota are caused by something. What? The Star Tribune isn’t yet ready to tackle that question.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.