The Surplus: Simplify taxes for Minnesotans

On Dec. 7, Minnesota Management and Budget (MMB) released its budget forecast for Fiscal Year 2022-23 which foresaw a $7.746 billion projected surplus. This immediately sparked a debate about what should be done with that money.

For a number of reasons, it should be given back to the people who earned it — ordinary, hard working Minnesotans — via tax cuts.

Minnesota’s tax regime is complex

While the primary problem facing Minnesota in tax policy is excessive tax rates, our state also suffers from needless tax complexity. This complexity adds to the burden Minnesota’s tax system places on its residents and businesses.

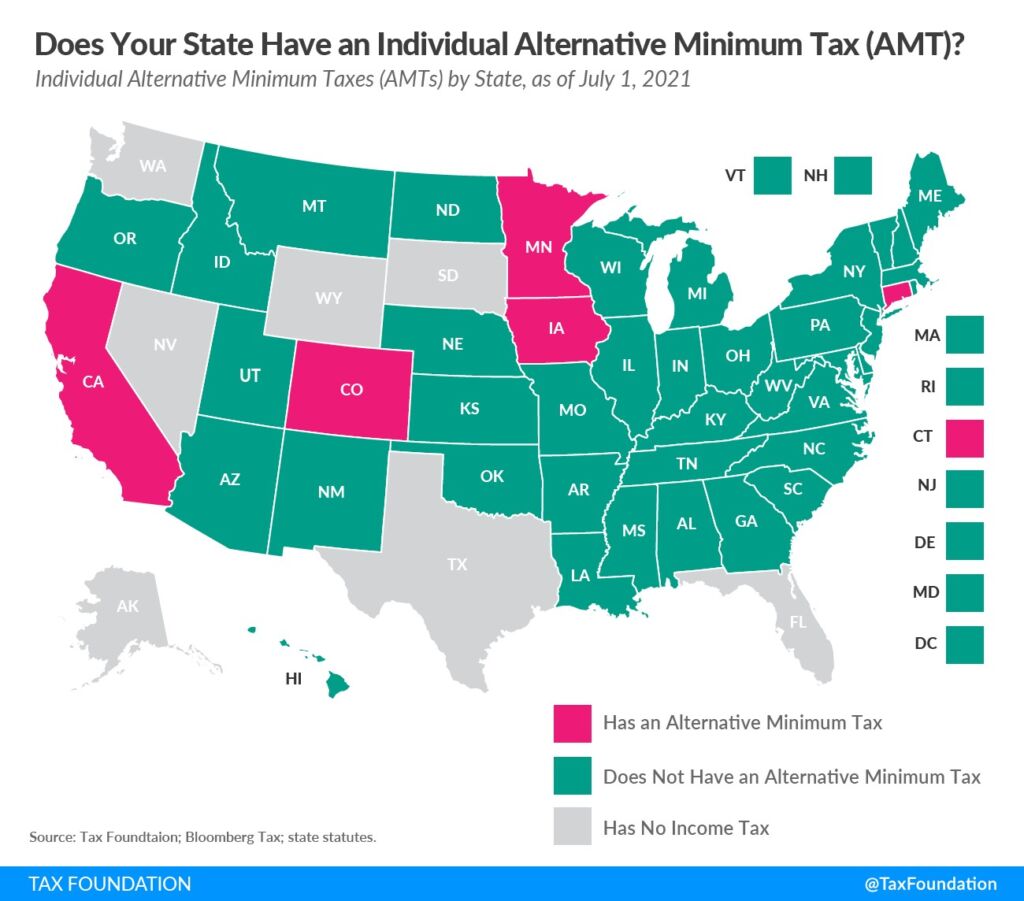

Alternative Minimum Tax for individuals

Minnesota is one of just five states that impose an Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) for individuals.

The federal AMT was created in 1963 to prevent high-income taxpayers from reducing their tax burden below a certain limit. It did so by requiring certain individuals to calculate their taxes twice. Several states followed the federal lead and implemented their own AMTs, which meant that some taxpayers had to calculate their tax liability four times: twice under the federal code and twice under their state’s code.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act increased the federal AMT’s exemption amounts and phaseout thresholds through 2025, so fewer taxpayers will be required to calculate and pay the federal AMT in future. Minnesota’s individual AMT does not conform exactly to the federal provision — it does not allow for the deduction of home mortgage interest and has one flat rate, while the federal AMT has two rates — so filers have to go through the process of calculating a state AMT even if no longer subject to a federal AMT.

The Minnesota AMT was estimated to raise about $23.6 million in tax year 2017, from about 9,500 taxpayers, or 0.1 percent of total state tax collections. While the number of taxpayers paying the state AMT is expected to increase in future years as real income increases and as AMT preference items, such as home mortgage interest and property taxes, increase more rapidly than inflation, the original goal of the AMT — to prevent deductions from eliminating income tax liability altogether — can be better achieved by simplifying the existing tax structure, not by instating an alternative tax which adds complexity and lacks transparency and neutrality.

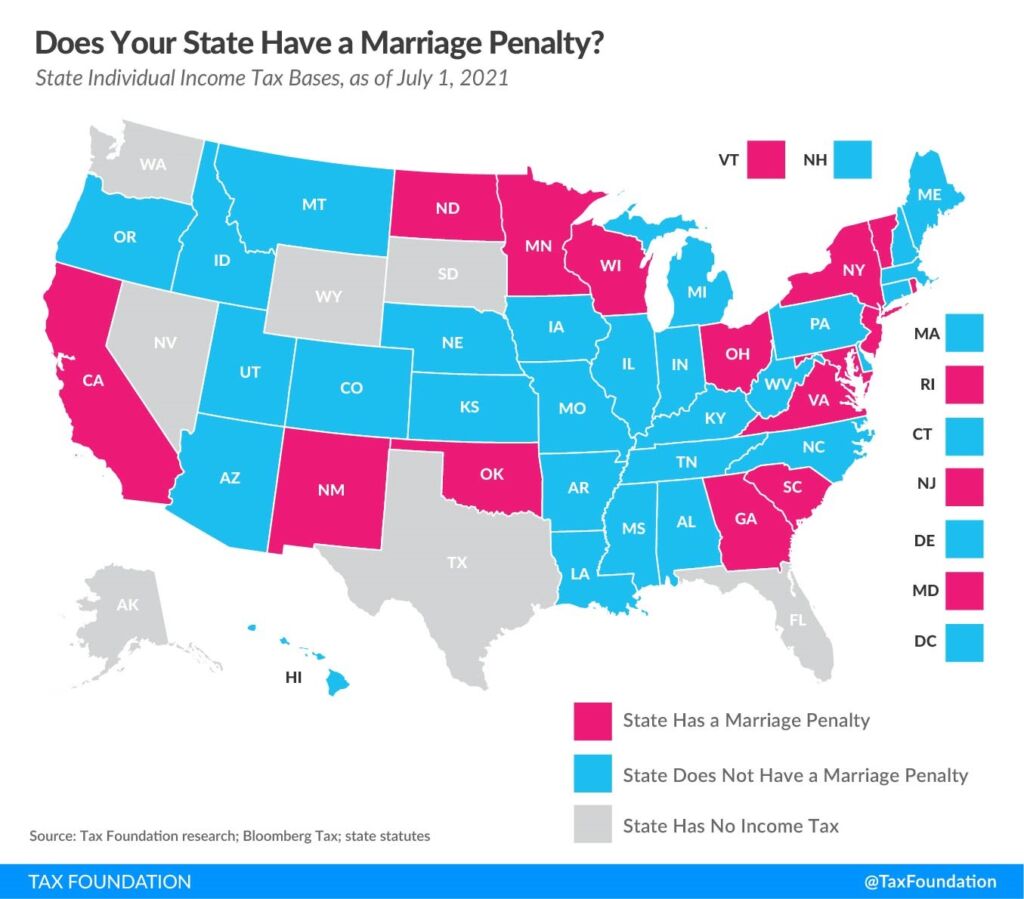

Marriage tax penalty

Minnesota is one of fifteen states to have a ‘marriage tax penalty’ built into its tax code.

Under a graduated-rate income tax system such as Minnesota’s, a taxpayer’s marginal income is subject to progressively higher tax rates. When a state’s standard deduction and tax brackets for married taxpayers filing jointly are less than double those for single filers, a ‘marriage tax penalty’ is said to exist. In other words, married couples who file jointly under this scenario have a higher effective tax rate than they would if they filed as two single individuals with the same amount of combined income.

A marriage tax penalty is not only discriminatory by penalizing marriage in the tax code, it also has negative economic consequences. Owners of pass-through businesses pay taxes on their business income under the individual income tax system. With a marriage tax penalty in place, married business owners are subject to higher effective tax rates on their business income than they would be otherwise. This is a real problem given that married couples dominate the top-earning 20 percent of taxpayers — they account for 85 percent of that category — and that the same top-earning 20 percent also has the highest concentration of business owners of all income groups. Because of these concentrations, marriage penalties have the potential to affect a significant share of pass-through businesses.

Simplify Minnesota’s income taxes

Tax burdens aren’t only functions of the rates but also of the ease of complying with the laws. The more difficult that is, the more burdensome taxes are.

The existence of the individual AMT and marriage tax penalty in Minnesota make our state’s taxes more complex and burdensome than they need be. State legislators should get rid of both.