University of Chicago: Renewable Energy Mandates Increase Electricity Costs

The University of Chicago made waves last week by releasing the findings of a working paper that found renewable energy mandates cause electricity prices to rise. This won’t be surprising to our readers, but it is massive vindication for all the hard work American Experiment has put into educating the general public about the negative consequences of renewable energy mandates.

From the abstract of the paper:

“Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) are the largest and perhaps most popular climate policy in the US, having been enacted by 29 states and the District of Columbia. Using the most comprehensive panel data set ever compiled on program characteristics and key outcomes, we compare states that did and did not adopt RPS policies, exploiting the substantial differences in timing of adoption.

The estimates indicate that 7 years after passage of an RPS program, the required renewable share of generation is 1.8 percentage points higher and average retail electricity prices are 1.3 cents per kWh, or 11% higher; the comparable figures for 12 years after adoption are a 4.2 percentage point increase in renewables’ share and a price increase of 2.0 cents per kWh or 17%. These cost estimates significantly exceed the marginal operational costs of renewables and likely reflect costs that renewables impose on the generation system, including those associated with their intermittency, higher transmission costs, and any stranded asset costs assigned to ratepayers.

The estimated reduction in carbon emissions is imprecise, but, together with the price results, indicates that the cost per metric ton of CO2 abated exceeds $130 in all specifications and ranges up to $460, making it least several times larger than conventional estimates of the social cost of carbon. These results do not rule out the possibility that RPS policies could dynamically reduce the cost of abatement in the future by causing improvements in renewable technology.”

The study is interesting specifically because it does not use a Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) methodology to calculate the cost for three main reasons 1) Most LCOE analyses do not account for the costs associated with the intermittency of wind and solar, 2) LCOE analyses often do not account for transmission costs, and 3) RPS driven increases in renewable energy penetration can also raise total energy system costs by prematurely displacing existing productive capacity, especially in a period of flat or declining electricity consumption.

We’ve discussed how intermittency imposes costs on the electric system many times, but the Chicago study had very interesting things to say about transmission:

A literature review of transmission cost estimates for wind power by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) finds a median estimate of about $300 per kW, or about 15% of overall wind capital costs (Mills et al., 2009). This is approximately equivalent to adding 1.5 cents per kWh to the levelized cost of generation for wind. More generally, a separate analysis by the Edison Electric Institute in 2011 found that 65% of a representative sample of all planned transmission investments in the US over a ten-year period, totaling almost $40 billion for 11,400 miles of new transmission lines, were primarily directed toward integrating renewable generation.4 The highly disproportionate share of transmission requirements for renewables relative to their share of generation highlights the importance of accounting for the associated costs as part of the total cost of renewable energy [emphasis added].

Lastly, stranded assets and idle capacity make up the last major component that is often lost in LCOE analyses:

Adding new renewable installations, along with associated flexibly dispatchable capacity, to a mature grid infrastructure may create a glut of installed capacity that renders some existing baseload generation unnecessary [emphasis added]. The costs of these “stranded assets” do not disappear and are borne by some combination of distribution companies, generators, and ratepayers. Thus, the early retirement or decreased utilization of such plants can cause retail electricity rates to rise even while near zero marginal cost renewables are pushing down prices in the wholesale market. The incidence of excess capacity costs on ratepayers is likely greater in regulated markets with vertical integration, although even in deregulated markets there are various mechanisms for direct payments to producers unconnected to actual generation that can contribute to the rates consumers face.

On the impact of mandates:

“Electricity prices increase substantially after RPS adoption. The estimates indicate that in the 7th year after passage average retail electricity prices are 1.3 cents per kWh or 11% higher, totaling about $30 billion in the RPS states. And, 12 years later they are 2.0 cents, or 17%, higher. The estimated increases are largest in the residential sector, but there are economically significant price increases in the commercial and industrial sectors too. These estimates are robust to controlling for local shocks to electricity costs in a variety of ways.”

On reducing carbon dioxide emissions:

When the CO2 emissions estimates are combined with the estimated impact on average retail electricity prices, the cost per metric ton of CO2 abated exceeds $130 in all specifications and can range up to $460, making it at least several times larger than conventional estimates of the social cost of carbon.

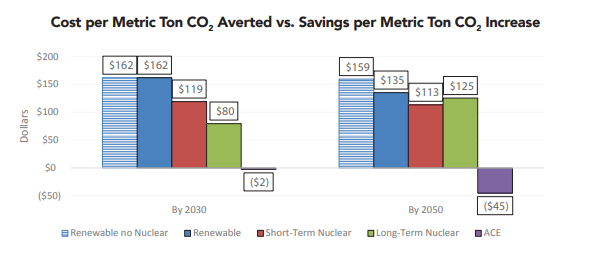

This finding was especially interesting to me because our study, Doubling Down on Failure, the cost of each metric ton of CO2 averted using a 50 percent renewable energy mandate would cost $135 dollars, and this would increase to $159 per metric ton if the nuclear plants are closed down. Our estimates are very conservative because assume the wind and solar will be perfectly integrated into the grid, and none of it will be wasted, or curtailed.

I’ve been writing this blog post as I read the report and the more I read, the more I like it. The main problem with studies commissioned by renewable energy advocates, like the VCE study that incorrectly claims wind and solar are cheaper than existing coal, is that they focus on the unsubsidized costs of wind or the values of power purchase agreements (which include subsidies), and ignore the load-balancing costs of intermittency, the transmission costs renewables foist on the system, and they ignore how regulatory structure guarantee profits for utility companies and require consumers to pay for two electric grids, one that produces electricity when the weather cooperates, and one for when it does not.

Unfortunately, DFL lawmakers have been quoting VCE studies and the LCOE cost estimates from Bloomberg New Energy Finance as gospel, without really understanding that these cost estimates have serious shortcomings. As such, the cost estimates are just a small piece of a much larger puzzle. Stated otherwise, they’re just the tip of the iceberg.