Venezuela hikes its minimum wage and trashes employment. What are the lessons for Minnesota?

I’ve written before about the dreadful economic and social collapse in Venezuela, formerly the poster child for ‘democratic socialists’ like Sen. Bernie Sanders. It is heartbreaking to see the people of Venezuela reduced to lab rats in another experimental proof of the the awfulness of socialist economics. But there are lessons in this and the least we can do is learn from them.

Venezuela’s currency is collapsing in value. As Forbes reported recently,

The price of a cup of coffee, measured using Bloomberg’s Café Con Leche Index, is now more than 2,000,000 bolivars. That is up from 1,400,000 bolivars last week and 190,000 in April. The 3-month annualized inflation rate is over 1,200,000%. That is hyperinflation not seen in the world since Germany in the 1920s or Zimbabwe in 2008.

The Venezuelan government’s solution is, of course, to pile bad economic policy upon bad economic policy. To help a population ravaged by this hyperinflation, the minimum wage has been hiked. And, as Bloomberg reports, ‘Venezuela Raises Minimum Wage 3,000% and Lots of Workers Get Fired’

Venezuelan workers who earned a pittance are now earning a slightly larger pittance, thanks to a big increase in the minimum wage. What they may not have are jobs.

Starting this week, 7 million employees are guaranteed 1,800 bolivars a month — worth about $20 at the black-market rate. President Nicolas Maduro intended the mandate as political boost, but it’s having the opposite effect as companies, already hit by Venezuela’s epic economic contraction, tell workers they can’t afford to keep them.

While there have been many similar moves in the past, never has one been so disruptive, arriving amid hyperinflation, depression and devaluation. Some employers are restructuring costs, rejiggering pay scales and negotiating settlements with workers. Others are simply dismissing people. Much of the action happens secretively as companies try to avoid punishment by the government, which has been jailing those it believes are flouting the rules.

Why does this matter for Minnesota?

This is awful. Even a democratic socialist might admit that things are not going to plan in Venezuela. But, they might ask, what does it have to do with us here in Minnesota? Activists here are not advocating for those kinds of wage hikes, just increases of between 55% and 90% in Saint Paul.

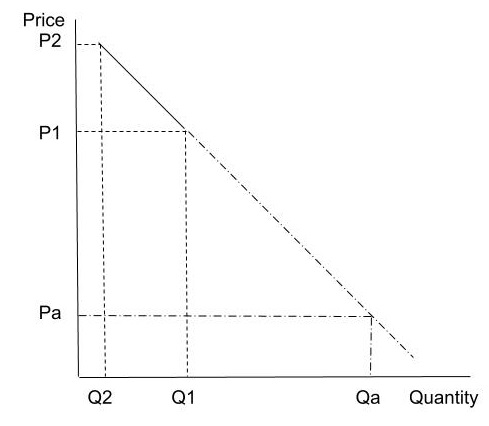

Figure 1 shows what has just happened in Venezuela. The minimum wage hike raised the price of labor from P1 to P2. As a result, employment, the quantity of labor demanded, is falling from Q1 to Q2. The demand curve for labor slopes down and to the right, in other words.

Figure 1 – The demand curve for labor

But if the demand curve for labor slopes down and to the right between P1 and P2, why would we assume that it behaves differently below P1? There is no reason to assume it does. If we carry on sketching the demand curve down and to the right, we would see that minimum wage hikes at lower levels than Venezuela’s 3,000% – the 55% to 90% proposed in Saint Paul, say – would also reduce the quantity of labor demanded – in this case, from Pa to P1. Indeed, the majority of empirical literature, which shows that minimum wages reduce employment opportunities for less-skilled workers, suggests that it does.

It is true that Venezuela is an extreme example. But extreme examples start off as less extreme examples. If you ask an advocate for minimum wage hikes ‘Why not just make it $500 an hour?’ and they respond with ‘That’s just silly’, ask them why they think it silly. It is a tacit admission that demand curves slope down and to the left. And if they do it at ‘extreme’ or ‘silly’ wage rates, why not at lower ones?

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.