What the American Experiment means to me

Working at Center of the American Experiment, I’m often asked, “What is the American Experiment?” It’s a fair question, and one that I’ve pondered often on long drives around the state.

“This idea…”

I always come back to Ronald Reagan. Growing up in Britain in the ‘80s, he, along with Madonna, Michael Jackson, and Eddie Murphy, was the face of America to me. In his famous 1964 speech “A Time For Choosing,” he said:

This idea that government is beholden to the people, that it has no other source of power except the sovereign people, is still the newest and the most unique idea in all the long history of man’s relation to man.

He asked:

…whether we believe in our capacity for self-government or whether we abandon the American revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.

This, he claimed, was “the issue of this election.” To some degree, it has been the issue of most elections. And it was, as Reagan said, the issue of the American revolution.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident…”

In the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia 243 years ago today, the Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence. It contains the words:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

In fact, on July 4, 1776, these truths would have been self-evident almost nowhere outside the Pennsylvania State House. In Russia, for example, serfs would suffer under the brutal lash of Tsarist autocracy for another nine decades. In France, the Bourbon monarchy was wringing ever-larger sums of taxation out of the disenfranchised peasantry to pay for its military adventures and courtly extravagances, while exempting the only people who were rich enough to actually pay them. Tsar and serf, king and peasant, were not created equal: there were no rights that the ruler couldn’t take away: liberty and happiness were in short supply.

If anyone could have understood the American revolutionaries it should have been the British who cut off a king’s head in 1649 to prove the point that all men were equal under the law. It is one of history’s ironies that the colonists rebelled against one of the more politically enlightened regimes of the time. But even in Britain, Parliament still had much work to do before it would bring the monarchy to heel. The last living signatory of the Declaration of Independence — Charles Carroll — died aged 95 in 1832, the same year the Reform Act grudgingly gave the vote to the rising capitalist class being created by the Industrial Revolution. The experiment in self-government which the 56 signatories of the Declaration were embarking on was a specifically American one.

“…conceived in Liberty…”

Their words were often more honored in the breach than in the observance. Some of those who wrote that “all men are created equal” had slaves at home. Those slaves — bought and sold like cattle, worked relentlessly, punished mercilessly — suffered more under America’s presidents than Russian serfs or French peasants did under Tsar or king. It is hard to reconcile how some of the authors of such visionary rhetoric could behave like that. It is certainly beyond me.

It is fashionable nowadays to dismiss the words of the Declaration of Independence on these grounds as shallow hypocrisy. This is wrong. Its words have a life of their own. They do not depend for their meaning and power on the men who wrote them. If they did their practical use would have died with Charles Carroll. And because they had those words — those ideas — subsequent generations of Americans were able to work on delivering on the unfulfilled promises of America’s founding.

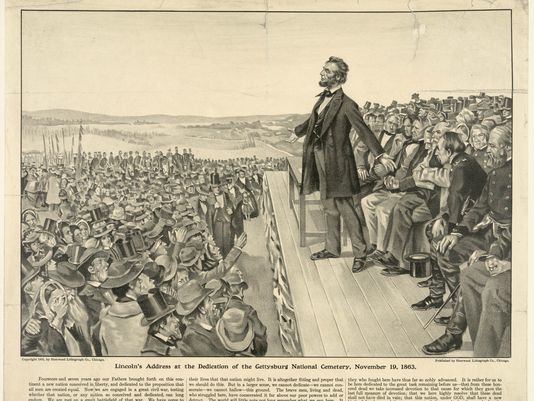

The campaign to end the evil of slavery was able to draw, as Lincoln did in his immortal Gettysburg address in 1863, on the Declaration of Independence, and those truths that were held to be self-evident. When he lead the March on Washington a century later and delivered his ‘I Have a Dream‘ speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said:

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men – yes, black men as well as white men – would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

When, in 1965, Frank Kameny became the first person to challenge his firing from federal government employment on the grounds of sexual orientation, he grounded his arguments for equality in the language of the Declaration of Independence.

By contrast, where these ideas were absent, as in the French and Russian revolutions, oppression worse than that of the old regime quickly followed. The French revolution rapidly degenerated into wholesale slaughter under the Jacobins, and the Russian revolution ushered in the terror of the cheka. That is why there is no “French experiment” and only fossilized fools like Bernie Sanders pine for the failed “Soviet experiment.” Those truths held self-evident, of the unalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are the basis of this American Experiment.

“shining city on a hill”

The ideals of the Declaration of Independence are shared much more widely now than they were in 1776. As of the end of 2017, 96 out of 167 countries with populations of at least 500,000 were democracies of some kind, and only 21 were autocracies. Americans are sometimes apt to think that they belong to a “young” country. They do not. Both Italy and Germany are younger than the state of Minnesota. France might be an old country, but its constitution is the same age as ‘Peggy Sue’ by Buddy Holly. These countries have had the example of the American Experiment to guide them. This country has admirably fulfilled the hopes of John Winthrop and been that “shining city on a hill.” That light has drawn people here from all over the world, including me.

“A republic, if you can keep it”

This is a long answer to a short question, but they are long drives. Put more succinctly, the American Experiment is, to me, about liberty: the liberty to live your life as you see fit and to pursue happiness in your own way, as long as it doesn’t impede anyone else’s pursuit. The flipside of this is responsibility, which can be scary. But only by remaining forever a child, with the government as the parent, can a person avoid some measure of that.

There are countless policy prescriptions that flow from this, and you’ll find many of them discussed on our website. But, behind them all, are the words written by those 56 flawed, visionary human beings in Philadelphia 243 years ago which inaugurated the American Experiment: that all men — and women — having been created equal, have the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.