Why are academic declines so shocking?

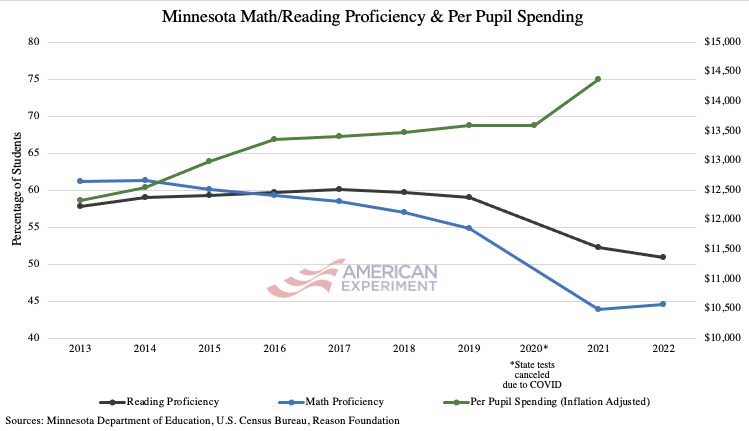

I recently wrote about another round of assessment results capturing the continual fall in academic achievement among our country’s students. While the declines were certainly exacerbated by government policy responses — school closures came at a stiff price — they existed pre-COVID.

In fact, it was because of these pre-COVID downward learning trends that caused many of us to sound the alarm on state education leaders stubbornly sticking by their shutdown decisions, particularly as data quickly emerged showing that prolonged school closures would have devastating effects on students’ cognitive, social, and emotional well-being.

And the data have come true. Now, many responsible for prolonging this public policy response are feigning shock and backtracking their previous stances on school re-openings.

While there has been a recent call for “urgency and focus” around recovery efforts, it is unfortunate there hasn’t been the same sense of urgency over the past decades. The rising tide of mediocrity is now a tsunami of poor performance. The falling trajectory of student scores and the widening of academic gaps aren’t new and reinforce the importance of ensuring students can access the learning environment that will meet their needs.

For example, fourth-grade students attending Catholic schools didn’t lose ground in math in 2022 compared to their government school peers, and eighth-grade students in Catholic schools actually increased their reading scores compared to their 2019 scores, whereas their public school peers saw a decline in scores.

Additionally, recent research shows Mississippi has fully recovered its reading learning loss and had the greatest test score recovery in math compared to the other 20 states (including Minnesota) analyzed. Minnesota experienced the least recovery in math and in reading did not recover at all, with student scores dropping nearly nine percent in 2022 compared to pre-COVID results. Mississippi spends far less per student than Minnesota and has focused its dollars on reading literacy, which includes a third-grade promotion law. Mississippi also has three private school choice programs — two school voucher programs and an education savings account program, all of which help families send their children to participating private schools. Minnesota does not offer families either of these.

If there is a silver lining to COVID, it was the “awakening” of parents to what their children were — or weren’t — learning. We have “a historic opportunity to set a new direction for American K-12 education,” writes James Hankins, a professor of history at Harvard University. “It will take serious reform for unionized school districts to regain the confidence of the public, given the entrenched economic and political interests that protect mediocrity and encourage political zealotry.”

This is not to dismiss the ideals that gave rise to the public school system more than a century ago. The creation of America’s public school system was surely one of the great triumphs of the Progressive movement, and for a long time that system represented a vast improvement on the educational resources previously available to Americans. For most of the twentieth century, the public schools were egalitarian, public spirited, and helped integrate waves of immigrants from all over the world into a common American culture. In their original form, they provided well-trained teachers who respected American and Western traditions. They taught civics without trying to use the classroom to force radical change on American society—despite efforts from the followers of John Dewey to do just that.

…

But all things human are subject to decay. The decline in both the quality and sanity of public schools in recent decades has now, thanks to the experiences of 2020-21, become obvious to many more parents and concerned citizens.