Why cigarette taxes don’t work

Last August, I asked ‘Why do we tax people?’ I reckoned that the most common answer would be ‘To pay for stuff’. But that is not the only reason governments levy taxes. Another is to discourage people from doing certain things. A tax, after all, is a negative incentive – if you tax something more, you get less of that thing. Outgoing Governor Mark Dayton embraced this logic when he supported higher cigarette tax rates, arguing that the cigarette tax “has been an effective tool in discouraging smoking, especially among young people”.

Not so fast. A 2012 paper for the NBER by economists Kevin Callison and Robert Kaestner asked the question ‘Do Higher Tobacco Taxes Reduce Adult Smoking?‘. They found that

Estimates indicate that, for adults, the association between cigarette taxes and either smoking participation or smoking intensity is negative, small and not usually statistically significant. Our evidence suggests that increases in cigarette taxes are associated with small decreases in cigarette consumption and that it will take sizable tax increases, on the order of 100%, to decrease adult smoking by as much as 5%.

Elasticities matter

Does this mean that taxes are not, in fact, negative incentives? Is Gov. Dayton barking up the wrong tree?

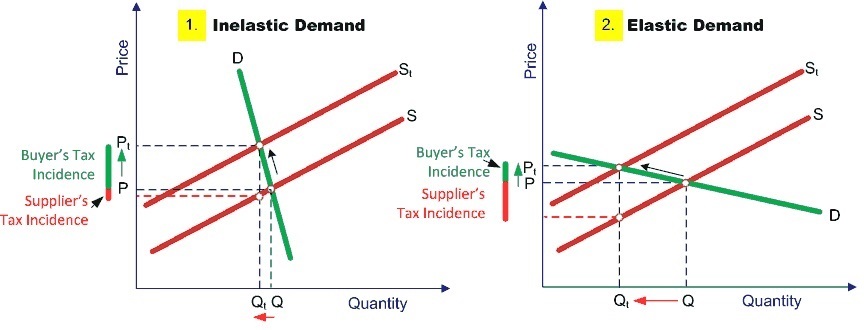

Note that Callison and Kaestner found that cigarette taxes did reduce smoking, just not by very much. Demand for cigarettes is ‘inelastic’, in other words. The left hand panel of Figure 1 illustrates this. An increase in price from P to Pt resulting from a tax increase produces a fairly small fall in the quantity demanded, from Q to Qt. Contrast this with a good for which demand is ‘elastic’, illustrated in the right hand panel. Here, a small increase in price, from P to Pt, produces a relatively large fall in quantity demanded, from Q to Qt.

Figure 1

If you’ve ever been a smoker you can probably understand why demand for cigarettes is ‘inelastic’ (I quit seven years ago after about 15 years). You’re addicted. If you don’t get a cigarette within a certain amount of time you get fidgety, your start fiddling with things. There is an element of physiological dependence. This is why quitting can be so hard. Considering all this, you will suck up a rise in price unless it is huge, as Callison and Kaestner found. Given this, to really impact smoking, cigarette taxes would need to be some way higher than they are now.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.