Why we should all be concerned about declining marriage rates

“Did you know that nearly 50 percent of U.S. adults are single?”

In recognition of singles and unmarried people week, the US Census Bureau released data showing marriage trends in the U.S. According to the release, nearly 127 million adults are unmarried in the U.S. Out of those 127 million, 68 percent –– or nearly 87 million –– have never been married.

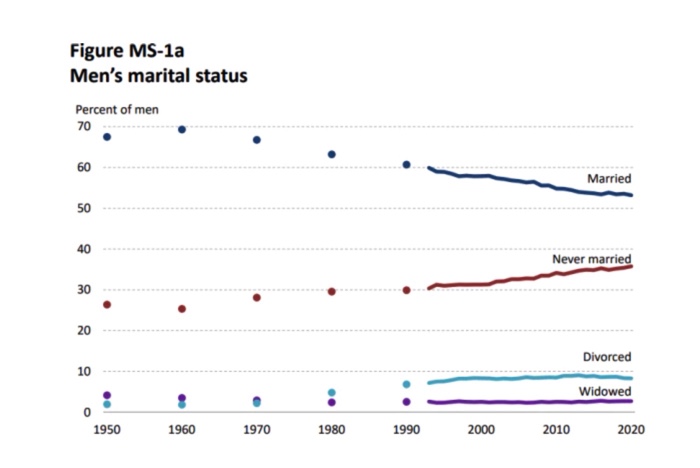

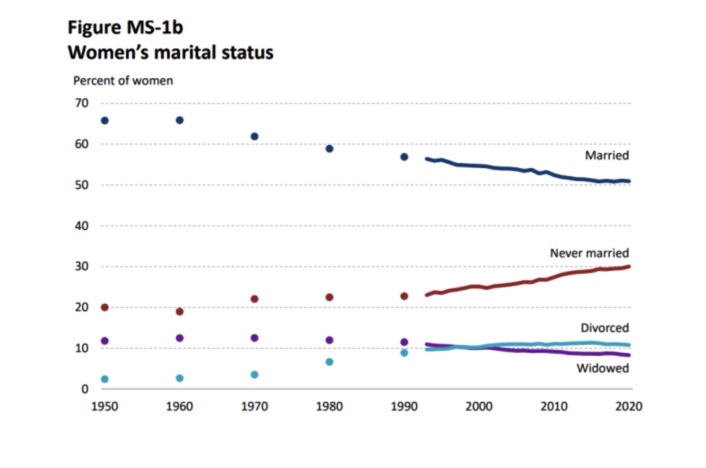

Declining marriage rates have been a long-running trend at least since the 1990s in the United States. The proportion of women who have never married, for example, reached an all-time high of 30 percent in 2020, compared to a low of 23 percent in 1990. Similarly, the proportion of men who have never been married rose from 30 percent in 1990 to 36 percent in 2020.

Why this matters

Marriages are proven to be generally beneficial for society: they provide order, stability and security to not only kids, but also individuals. Generally,

Decades of statistics have shown that, on average, married couples have better physical health, more financial stability, and greater social mobility than unmarried people.

Other studies show that the children of those couples are more likely to experience higher academic performance, emotional maturity, and financial stability than children who don’t have both parents in the home.

The effect of marriage on kids manifests itself visibly, especially through child poverty rates. Consider this evidence from a 2012 Heritage Foundation report:

The rise in out-of-wedlock childbearing and the increase in single parenthood are major causes of high levels of child poverty. Since the early 1960s, single-parent families have roughly tripled as a share of all families with children. As noted, in the U.S. in 2009, single parents were nearly six times more likely to be poor than were married couples.

Not surprisingly, single-parent families make up the overwhelming majority of all poor families with children in the U.S. Overall, single-parent families comprise one-third of all families with children, but as Chart 6 shows, 71 percent of poor families with children are headed by single parents. By contrast, 73 percent of all non-poor families with children are headed by married couples

How policy can help

Many factors go into deciding whether or not to get married. But in many ways, government policy can penalize marriage. One of the most obvious ways this happens is the tax code. The Minnesota tax code, for example, has a marriage penalty whereby a couple filing jointly faces a higher tax burden than that of two singles with the same combined income.

Welfare programs are also brimming with marriage penalties. Oftentimes, low-income married couples often lose welfare benefits once both their incomes are counted. This often leaves couples worse off economically than if they had been single or living together but not married, thereby disincentivizing marriage.

Economic conditions –– which are heavily influenced by policy –– also greatly affect marriage rates. In a 2012 Pew Research Survey, for example, 78 percent of women who had never married expressed that finding someone with a steady job is important for them in choosing a spouse or partner. Labor market conditions, therefore, to the extent that they prolong unemployment, may also delay marriage among individuals. In fact, some economic research does support the idea that increasing unemployment rates are associated with declining marriage rates.

Conclusion

Surely there is no easy solution to fixing America’s marriage problem. But given how fundamental marriage is to a well-functioning society, it would not hurt to pursue policies that encourage, rather than punish, marriage.