Wind company pleads guilty to killing at least 150 bald eagles

ESI, a subsidiary of the wind company NextEra Energy, pled guilty to killing at least 150 bald eagles over the past decade at its wind farms in eight states, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, North Dakota, and Wyoming.

The birds are killed when they fly into the blades of wind turbines. Some ESI turbines killed multiple eagles, federal prosecutors said.

According to the Associated Press:

NextEra President Rebecca Kujawa said collisions of birds with wind turbines are unavoidable accidents that should not be criminalized. She said the company is committed to reducing damage to wildlife from its projects.

“We disagree with the government’s underlying enforcement activity,” Kujawa said in a statement. “Building any structure, driving any vehicle, or flying any airplane carries with it a possibility that accidental eagle and other bird collisions may occur.”

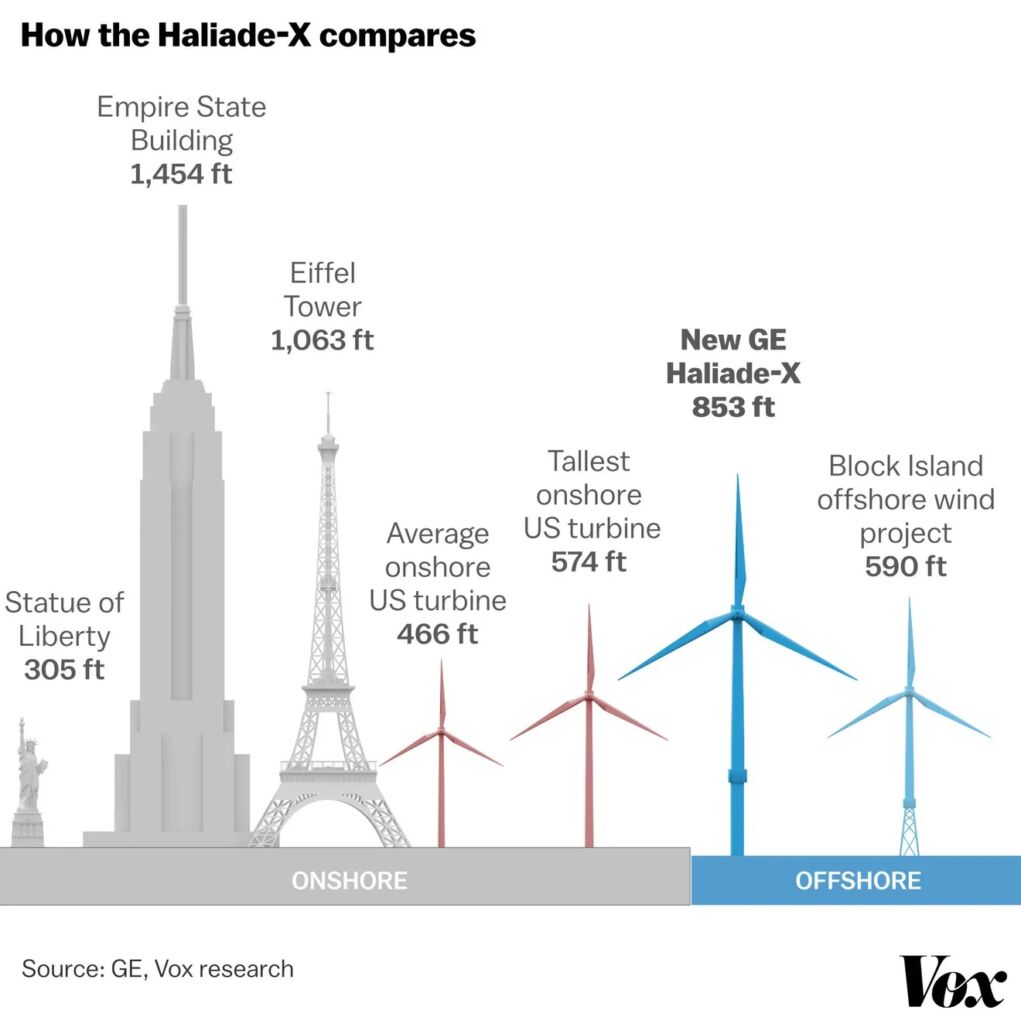

This argument is disingenuous, at best. How many people are driving their cars off the ground, 466 feet in the air?

While killing eagles is illegal under federal law, wind turbine owners don’t seem to be held to the same standard as everyone else. Environmentalist Micheal Shellenberger had a devastating Tweet on this topic:

It isn’t that other wind facilities don’t kill bald eagles; it is that ESI did not obtain permits to kill bald eagles or take steps to avoid the eagle deaths, which is why it is under federal prosecution.

In fact, ESI was warned prior to building the wind farms in New Mexico and Wyoming that they would kill birds, but they proceeded anyway and at times ignored advice from federal wildlife officials about how to minimize the deaths, according to court documents reported on by the Associated Press.

ESI agreed under a plea agreement to spend up to $27 million during its five-year probationary period on measures to prevent future eagle deaths. That includes shutting down turbines at times when eagles are more likely to be present.

Despite those measures, wildlife officials anticipate that some eagles could still die. When that happens, the company will pay $29,623 per dead eagle under the agreement.

Wind turbines are more likely to kill eagles than other energy sources because of their size and the fact that you need a lot more wind turbines to produce the same amount of energy, thereby increasing their geographic footprint.

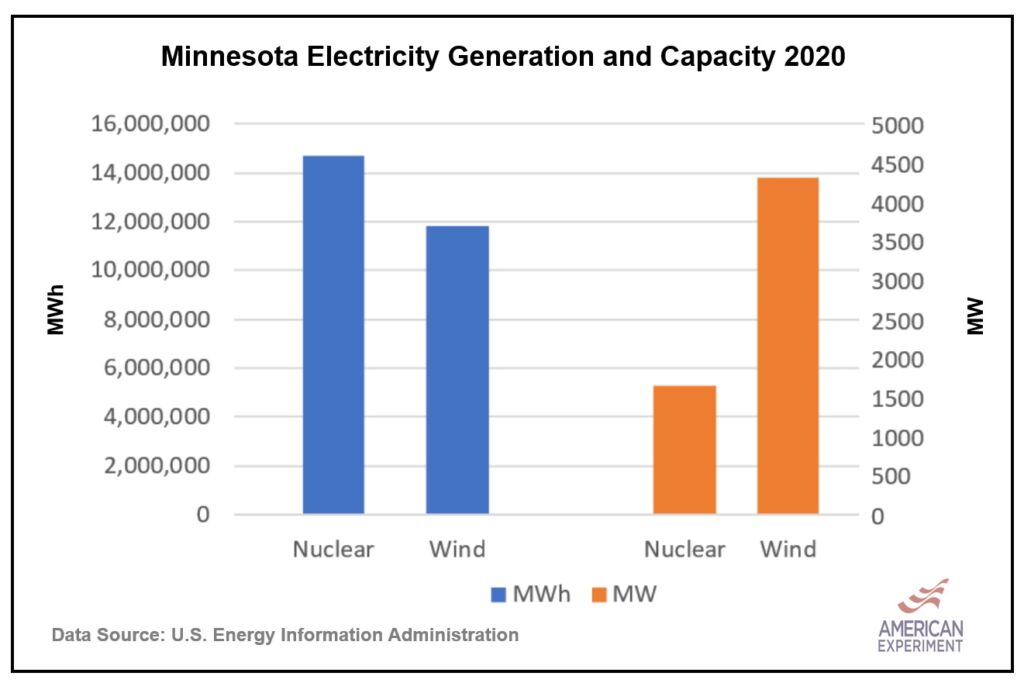

For example, the graph below shows that Minnesota’s nuclear power plants produced 24 percent more energy even though there is 2.6 times more installed wind capacity in the state than nuclear capacity.

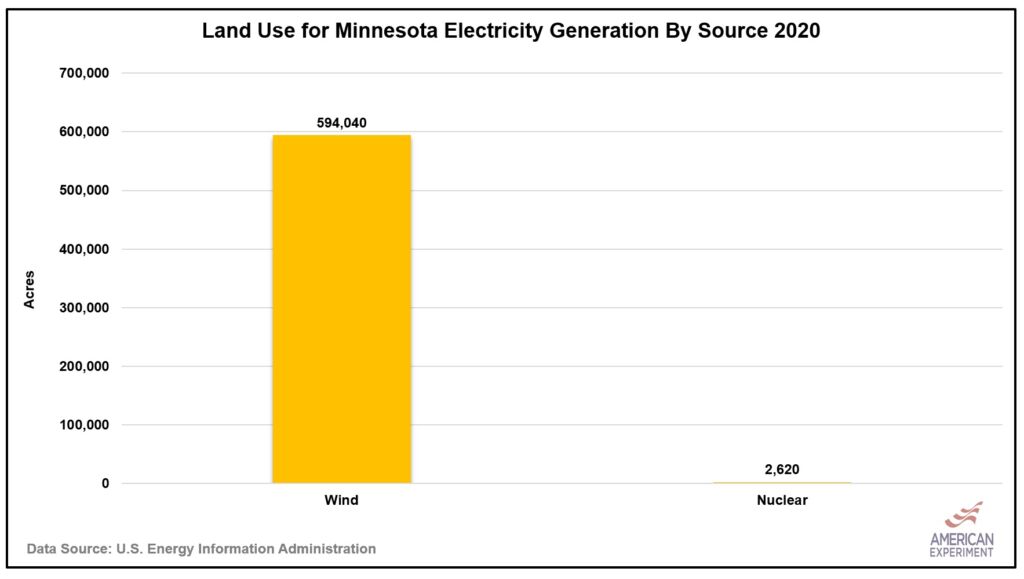

There is also a massive difference in the amount of land that this capacity consumes. According to the U.S. Energy information administration, Minnesota’s nuclear facilities have a combined capacity of 1,657 megawatts (MW) and sit on about 2,620 acres of land, which means nuclear plants in Minnesota require about 1.5 acres per MW.

In contrast, the Palmer’s Creek wind facility sits on approximately 6,150 acres of land and has an installed capacity of 44.6 MW, which means this facility needs approximately 138 acres per MW of installed capacity. If we apply this land-use requirement to Minnesota’s entire 4,308 MW of wind capacity, it yields a land-use requirement of 594,040 acres for Minnesota’s wind fleet.

This means wind turbines in Minnesota consume 226 times more land than nuclear power plants and produce 24 percent less energy. The difference in land use is shown in the graph below.

Not all wind turbine facilities will kill eagles, but the fact that we have spread wind turbines over nearly 600,000 acres of land has significantly increased the odds of collisions between wind turbine blades and bald eagles.

Understanding the environmental impacts of all energy sources is important for making informed decisions.

We could produce far more energy, use far less land, and pose far less danger to eagles if we prioritize energy sources with small geographic footprints. For this reason, we should legalize new nuclear power plants in Minnesota and use them to replace our existing coal-fired power plants when they reach the end of their useful lifetime.