Your guide to Lazard’s LCOE analysis Part 3: Why comparing new wind and solar costs to new coal, gas, nuclear makes no sense

Lazard’s LCOE analysis is frequently used by wind and solar advocates to claim that new wind and solar facilities are cheaper than new coal, natural gas, and nuclear plants.

However, the problem with this comparison is that it is like comparing the cost of a new Tesla to a new BMW when most Americans are perfectly happy to save money by continuing to drive their used Toyota RAV4s.

This article is Part 3 of our series on the Lazard LCOE analysis. You can click here to access the table of contents for these articles.

The biggest mistake

The biggest mistake wind and solar advocates make when citing Lazard’s LCOE analysis is to compare the cost of new wind and solar to the cost of new coal, natural gas, or nuclear power plants instead of comparing these costs to the existing power plants that are currently meeting our need for reliable electricity.

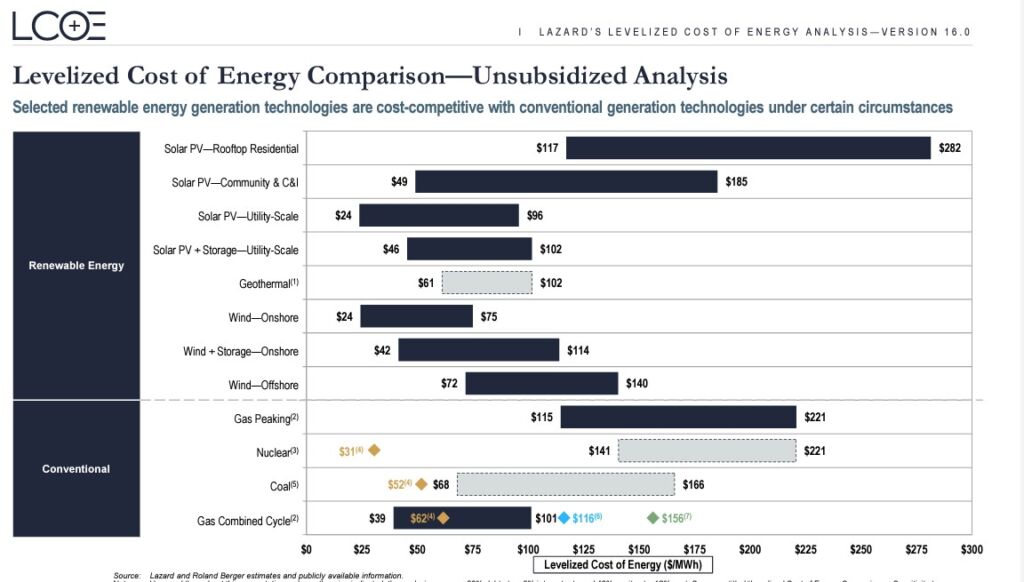

The graph below from Lazard shows a wide range of cost estimates for new wind, solar, natural gas, coal, and nuclear plants. New wind, for example, ranges from $24 per megawatt-hour (MWh) in the windiest places to $75 per MWh in the least-windy regions. This compares to $68 to $166 for new coal plants, with the high-end cost assuming the use of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) equipment.

However, these comparisons are missing the main point: we aren’t building an electric grid from scratch, so we should be comparing the cost of new wind and solar with the cost of existing power plants that these intermittent generators would hope to replace.

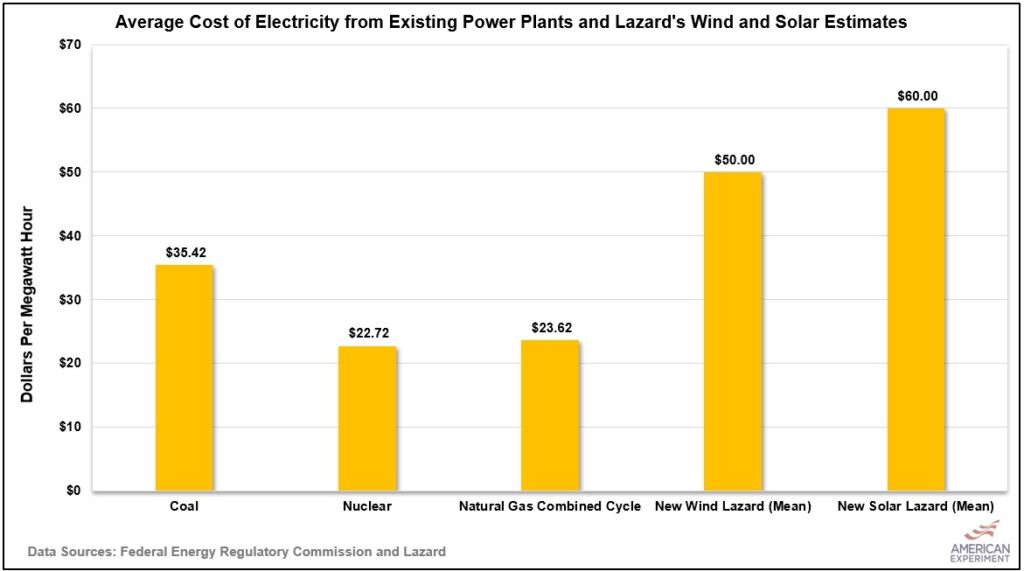

Using Form 1 data from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Mitch Rolling was able to calculate the average cost of electricity from existing coal, natural gas, and nuclear power plants throughout the United States, allowing us to compare the price of these facilities with the mean unsubsidized cost of wind and solar in 2023 found on page nine of the Lazard report.

The graph below shows wind and solar are much more expensive than the existing power plants they are theoretically replacing. In fact, new wind costs twice as much as existing nuclear or combined cycle natural gas plants.

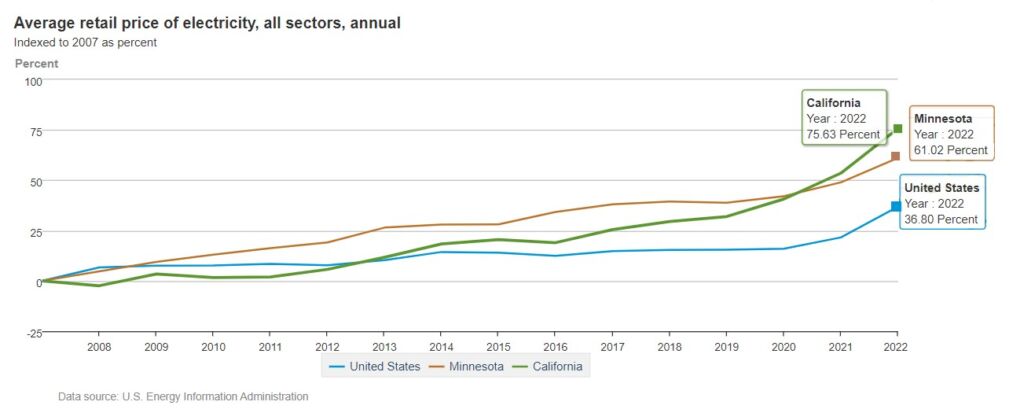

This means that building new wind and solar adds to the cost of providing electricity to the grid. If wind and solar were truly lower cost than other forms of energy, we would expect states like California and Minnesota, which have high penetrations of wind and solar, to see falling electricity costs. Instead, electricity prices in these states have increased much faster than the national average.

The graph above is from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. It shows California’s electricity costs have increased twice as fast as the national average since 2007, and Minnesota’s have increased 1.65 times faster. These rising costs are mainly due to mandates requiring the use of wind and solar in these states.

Why are older plants lower cost?

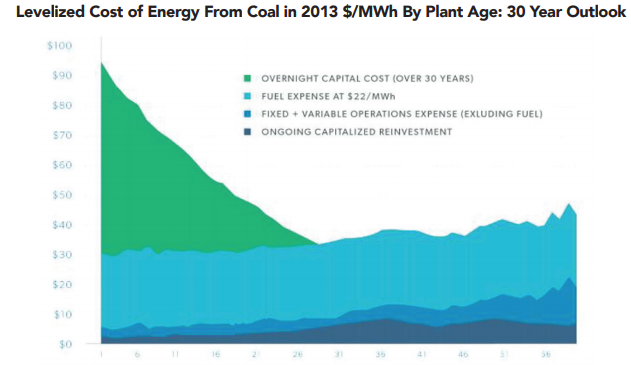

Existing coal, natural gas, and nuclear power plants are often much more affordable than new wind and solar facilities because the companies that own them have already paid back much of the upfront capital cost required to build them.

After the capital costs, or the “mortgage,” on the plant are paid off, it produces some of the lowest cost, most reliable power available, as you can see in the graphic below from the Institute for Energy Research. This is similar to your housing expenses declining after you finally paid off your home’s mortgage.

New wind and solar facilities compete with the existing generators on the grid. This existing grid, comprised of fully-depreciated coal, natural gas, and nuclear plants, can continue powering our lives and providing inexpensive electricity to families and businesses for years to come as long as we do not foolishly shut them down years before the end of their useful lifetime.

Unfortunately, wind and solar advocates are misleading lawmakers and the general public into supporting regulations that will shut down existing coal plants years before the end of their useful lifetime under the false premise that these weather-dependent resources are lower cost than the existing plants on the grid, which clearly isn’t true.

This is why policymakers should be looking to keep existing plants running for as long as it makes sense to run them. In doing so, they would be preserving quality assets that are providing the highest returns for families and businesses that require abundant, affordable energy.