Workplace Democracy for Minnesota’s Teachers is a Myth: Time to Update the Law

Teachers in the classroom today are being represented by an heirloom union that was selected by teachers a generation or more ago. I talked to Rookie at 1500 KSTP about it today (listen here).

Anyone old enough to watch the news back in the 1970s will remember the Minneapolis teachers’ strike in 1970. Along with the latest on the Vietnam war, I would catch the news in the kitchen with my mom when we were making dinner.

In April of 1970, teachers from the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers illegally went on strike for 14 days. Minneapolis educators were demanding better salaries, benefits and work conditions. But not all teachers were supportive of the strike, and the walkout created tension between strikers and non-strikers. It was a big deal; everyone was talking about it. (The kids where I went to school felt cheated that we did not get the same long break from school.)

Following the walkout, the Minnesota Public Employees Labor Relations Act (PELRA) of 1971 was enacted, granting public employees in the state the right to bargain collectively. In 1973, PELRA was amended to provide a limited right to strike.

I will write more about this over the next year as the Center rolls out our EducatedTeachersMN project, but suffice it say that allowing public employees the right to organize was still a very radical idea in 1970. The first government unions had only been around for about 10 years, with Minnesota following the national trend but very much leading what happened with teaching professionals.

Article II of the constitution of today’s teachers’ union, Education Minnesota, includes “workplace democracy” as one of its core objectives: “Education Minnesota shall be committed to democracy in the workplace and within the organization.”

But under PELRA, for teachers in the classroom today, workplace democracy does not include voting on whether teachers think the union has done a good job representing teachers.

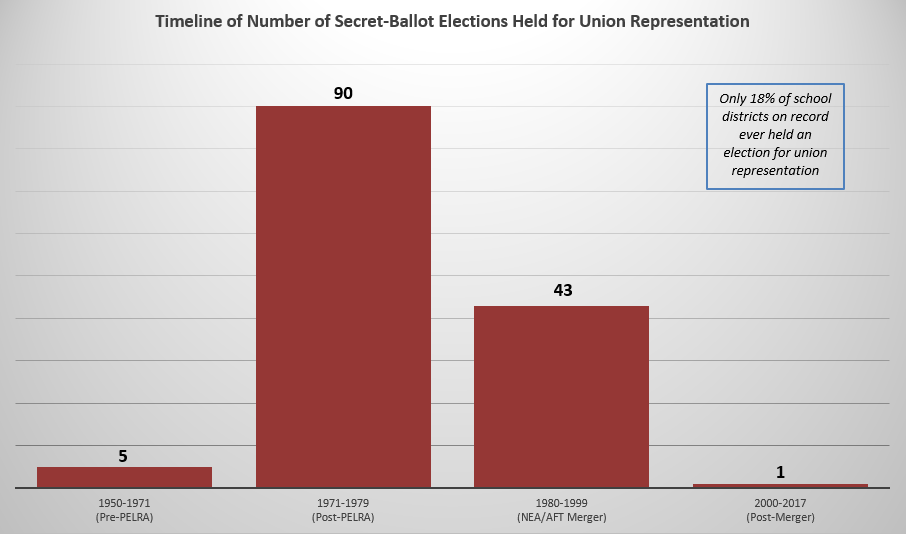

As you can see from the chart below, most of the actual votes for unionizing took place in the 1970s, with more to follow between 1980 and 1999. And then one in 2000 in the little district of Pine Point in Becker County.

According to the records at the state, only 18% of school districts represented by local unions ever held an election; the rest were done by various forms of joint agreement or grandfathering, though it is possible that the state records are incomplete.

State labor law PELRA offers flexible options for union recognition but only difficult and inflexible options for teachers to evaluate or replace the union with a new bargaining agent.

There are probably active classroom teachers who voted in turf wars that ensued between the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), and the merger that eventually followed in 1998. But all the teachers in the classroom today, are represented by a union that teachers chose generations ago. After PELRA passed, the power of the union consolidated quickly in what became “Education Minnesota.”

The idea of “workplace democracy” for public employees lives on in the union rhetoric but only on paper. Workplace democracy was strangled in its infancy in 1971 when PELRA was enacted with no provision for teachers to evaluate the performance of their union short of a decertification which has never been tried because it is a tough hill to climb for busy classroom teachers.

PELRA, in effect, handed Education Minnesota and its affiliates, monopoly bargaining power over public school teacher contracts and so much more (state policies related to education policy, and the employment of teachers).

How well has this served teachers?

It is time to update PELRA for the 21st century teacher and classroom.

(Featured photo from Patch News)