Urban Minority Students Aren’t Getting the Education They Need

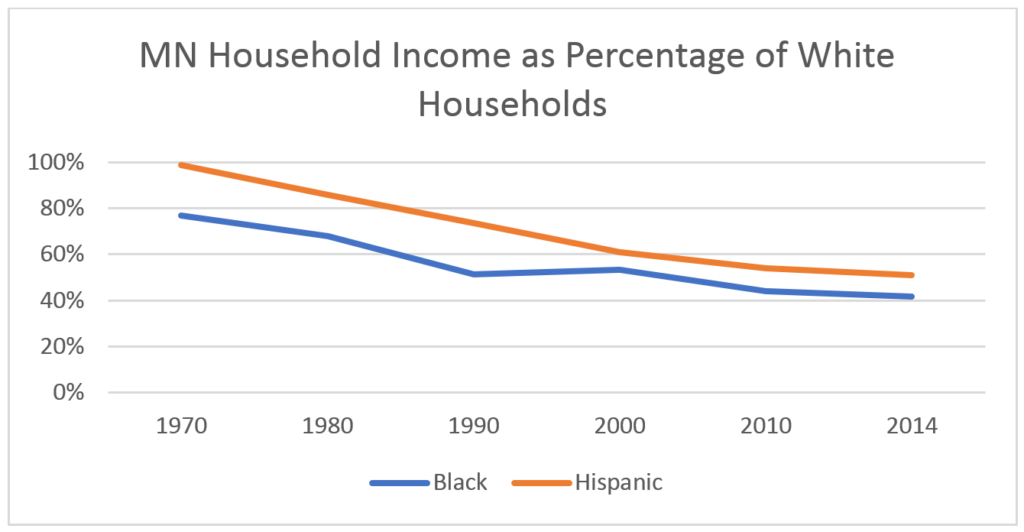

In 1970, Minnesota was among the states with the least income inequality. Black household median income was competitive with white households, and Hispanic incomes were nearly identical to white households. Since then, the racial wage gap has increased significantly despite remaining mostly unchanged in the rest of the country. By 2014, black families took home 42 percent what white families did, and Hispanic families barely made half.

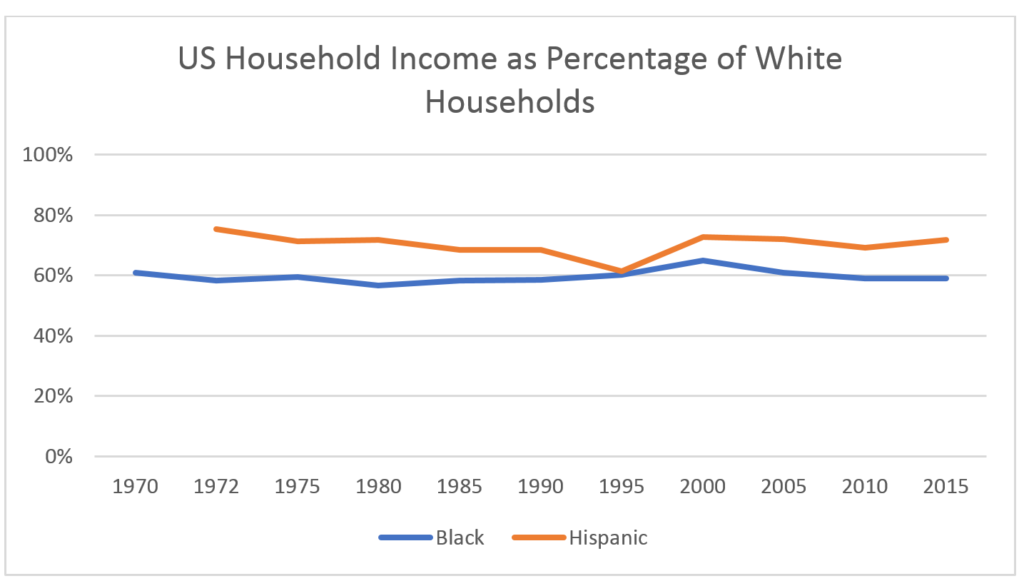

At the national level, this trend has not occurred. Households of color have made roughly the same relative to white households over time.

Why are black and Hispanic families so much worse off in Minnesota? The answer is likely the result of several variables. Immigration patterns, language barriers, and skill deficiencies may all contribute to Minnesota’s growing income gap.

One important factor, however, is the education system. Many Minnesotans will laud our K-12 education as top-notch, but it seems this is only the case for white students. In math, 68.8 percent of all white students in Minnesota meet or exceed standards, while only 30.1 percent of blacks and 36.3 percent of Hispanics perform at or above their grade level. For reading, 68.9 percent of whites meet or exceed standards, but only 34.8 percent of blacks and 38.9 percent of Hispanics do so. This is very concerning, and if education outcomes do not improve for people of color, it is unlikely the income gap will narrow.

It is often suggested that simply increasing school district budgets will solve our education problems, but this is not the case. The Minneapolis School District spent $20,502 per student in 2015, which is 44 percent more than the state average. All that spending didn’t lead to better outcomes, as only 44 percent of students met or exceeded standards in both math and reading. In 2017, Minneapolis’s student enrollment was 38 percent black and 18 percent Hispanic. These students are getting access to great funding, yet the education results remain subpar.

Instead of trying to spend our way to academic success, Minnesota can improve student outcomes by increasing choices for parents. These choices include creating a voucher program to pay some or all of the tuition fees for low-income students to go to private schools. These programs will make schools compete for students, which will force them to be more innovative and spend money properly.

A positive note is the expansion of charter school enrollment, especially among students of color. Although decades-old laws have allowed charter schools, charters enrolled only 8,000 students in the 2000 school year. In the 2016-17 school year, over 54,000 students enrolled. Hopefully, this increased choice will improve education results, allowing today’s students to close the racial wage gap in decades to come.

Income inequality is arguably the top issue people of color face in America today. Too often politicians in Minnesota and around the country try to solve this problem via income redistribution or increased spending without proper direction. These solutions only provide short-term relief but don’t improve low-income communities in the long run. The best way to improve economic and educational outcomes for people of color is by letting market forces do the heavy lifting, rather than the taxpayer.

Andrew Scattergood is a summer intern with the Center, a senior finance major at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management, and a graduate of Wayzata High School.