Assessing DFL legislative priorities: Childcare

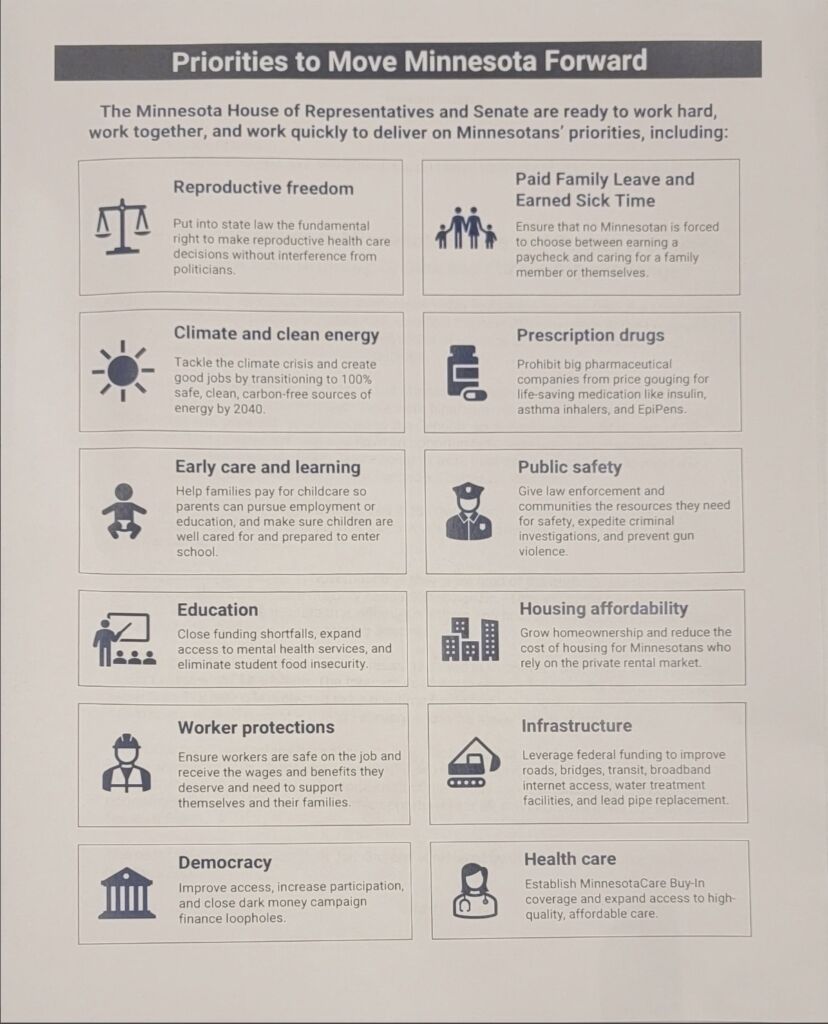

Among the DFL’s priorities to move Minnesota forward in the upcoming legislative session is the idea to increase funding for early care and learning. Specifically, the DFL wants to:

Help families pay for childcare so parents can pursue employment or education, and make sure children are well cared for and prepared to enter school.

But would spending money on childcare accomplish anything?

Certainly, the lack of affordable high-quality childcare is a big issue plaguing Minnesota families. But the childcare crisis exists because of government overregulation, something more funding will not solve.

Compared to other states, daycare centers in Minnesota follow more stringent rules, which raise the cost of providing care leading to high tuition. For example, to be a teacher at a licensed daycare center, someone with a bachelor’s degree must have over a thousand hours of work experience as an assistant teacher. But in other states, teachers are merely required to be adults and take some training before looking after children.

Minnesota also requires that someone with a high school diploma must have over two thousand hours of experience as an aide and college credits before they can be an assistant teacher. But even with such qualifications, assistant teachers can only look after children under the supervision of a teacher. Combined with the state’s low child-staff ratios and strict group size limits — especially for younger kids — providers have no wiggle room to keep costs down.

American Experiment research, for example, has found that if Minnesota allowed one staff to look after five infants, up from four, the annual cost of center-based care would go down by approximately $2,800. And if the state did not require childcare teachers to have post-secondary credits, the annual cost of infant care would be nearly $4,000 lower.

Spending money on childcare is unlikely to address the root cause of the childcare crisis. At best, such spending will increase demand while doing nothing to increase supply. This will raise prices further, consequently hurting low- and middle-income parents who are unable to access these subsidies. This is bad enough on its own, but evidence around the globe shows that free Pre-K programs do more harm than just raising prices. In Tennessee and Quebec, for example, while free Pre-K improved access to childcare, it also worsened health, social, cognitive, and educational outcomes among children involved in such programs.

The takeaway

It is a bad idea for the DFL to put taxpayers on the hook for spending that will not address the childcare crisis — and which might even do more harm than good.