Is America in for even higher inflation?

When I started studying for my economics degree in 2007, people’s eyes would glaze over when I told them what I studied. By the time I started my second year in September 2008, Lehman Brothers was filing for bankruptcy, the world economy was heading into the toilet, and, when I told people I studied economics, they now asked me what would happen to their jobs or the price of their house.

We are in one of those periods again. I go around the state talking about Minnesota’s economy, but when I throw the floor open to questions, I get an increasing number about the macroeconomy of the United States, especially inflation. People want to know if the current, elevated levels will persist or will they go even higher.

I don’t know, is the short answer, but then neither does Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. He said in July that inflation would be transitory, but is now saying that inflation might not be all that transitory after all. A good way to approach the question is to look at the factors that drive inflation and ask what is happening to them.

Money growth and inflation

In his academic and popular work, the economist Milton Friedman argued that:

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

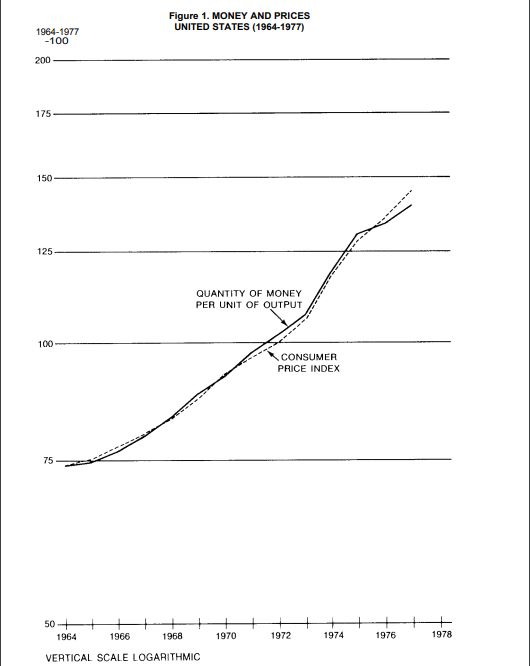

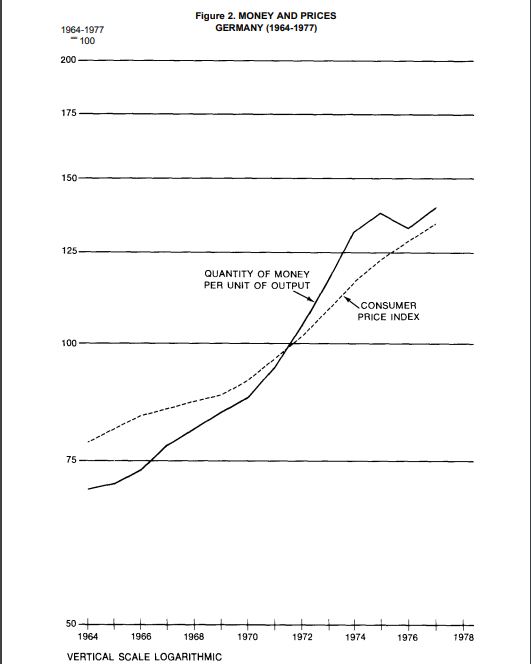

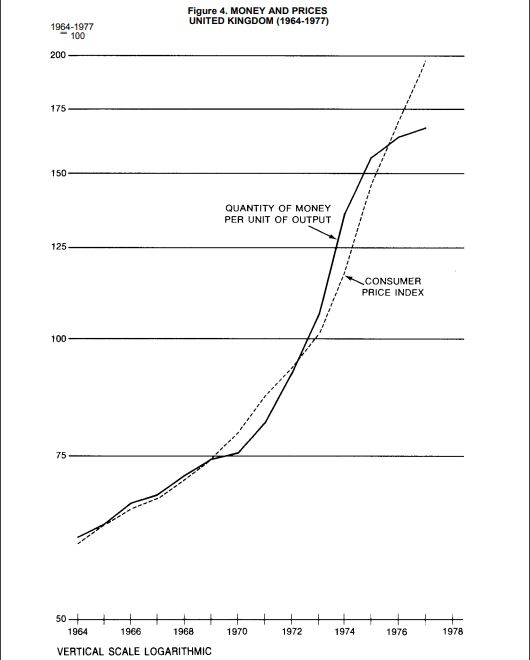

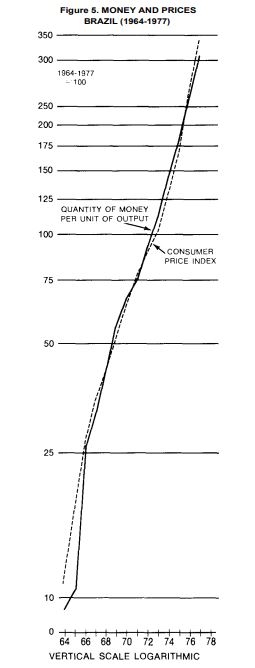

In his popular 1980 book Free to Choose, he produced a number of charts in support of this, showing the relationship between the money supply as measured by the quantity of money per unit of output and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for a number of countries:

These charts, Friedman argued, disposed of a number of common explanations of inflation:

Unions are a favorite whipping boy. They are accused of using their monopoly power to force up wages, which drive up costs, which drive up prices. But then how is it that the charts for Japan, where unions are of trivial importance, and for Brazil, where they exist only at the sufferance and under the close control of the government, show the same relation as the charts for the United Kingdom, where unions are stronger than in any of the other nations, and for Germany and the United States, where unions have considerable strength? Unions may provide useful services for their members. They may also do a great deal of harm by limiting employment opportunities for others, but they do not produce inflation. Wage increases in excess of increases in productivity are a result of inflation, rather than a cause.

Similarly, businessmen do not cause inflation. The rise in the prices they charge is a result or reflection of other forces. Businessmen are surely no more greedy in countries that have experienced much inflation than in countries that have experienced little, no more greedy at one period than another. Why then is inflation so much greater in some places and at some times than in other places and at other times?

Another favorite explanation of inflation, particularly among government officials seeking to shift blame, is that it is imported from abroad. That explanation was often correct when the currencies of the major countries were linked through a gold standard. Inflation was then an international phenomenon because many countries used the same commodity as money and anything that made the quantity of that commodity money grow more rapidly affected them all. But it clearly is not correct for recent years. If it were, how could the rates of inflation be so different in different countries? Japan and the United Kingdom experienced inflation at the rate of 30 percent or more a year in the early 1970s, when inflation in the United States was around 10 percent and in Germany under 5 percent. Inflation is a worldwide phenomenon in the sense that it occurs in many countries at the same time—just as high goverment spending and large government deficits are worldwide phenomena. But inflation is not an international phenomenon in the sense that each country separately lacks the ability to control its own inflation—just as high government spending and large government deficits are not produced by forces outside each country’s control.

Low productivity is another favorite explanation for inflation. Yet consider Brazil. It has experienced one of the most rapid rates of growth in output in the world—and also one of the highest rates of inflation. True enough, what matters for inflation is the quantity of money per unit of output, but as we have noted, as a practical matter, changes in output are dwarfed by changes in the quantity of money. Nothing is more important for the long-run economic welfare of a country than improving productivity. If productivity grows at 3.5 percent per year, output doubles in twenty years; at 5 percent per year, in fourteen years—quite a difference. But productivity is a bit player for inflation; money is center stage.

What about Arab sheikhs and OPEC? They have imposed heavy costs on us. The sharp rise in the price of oil lowered the quantity of goods and services that was available for us to use because we had to export more abroad to pay for oil. The reduction in output raised the price level. But that was a once-for-all effect. It did not produce any longer-lasting effect on the rate of inflation from that higher price level. In the five years after the 1973 oil shock, inflation in both Germany and Japan declined, in Germany from about 7 percent a year to less than 5 percent; in Japan from over 30 percent to less than 5 percent. In the United States inflation peaked a year after the oil shock at about 12 percent, declined to 5 percent in 1976, and then rose to over 13 percent in 1979. Can these very different experiences be explained by an oil shock that was common to all countries? Germany and Japan are 100 percent dependent on imported oil, yet they have done better at cutting inflation than the United States, which is only 50 percent dependent, or than the United Kingdom, which has become a major producer of oil.

“We return to our basic proposition,” Friedman wrote:

Inflation is primarily a monetary phenomenon, produced by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output. The behavior of the quantity of money is the senior partner; of output, the junior partner. Many phenomena can produce temporary fluctuations in the rate of inflation, but they can have lasting effects only insofar as they affect the rate of monetary growth.

What next for inflation?

If Friedman was correct and monetary growth is the primary driver for inflation, Americans have cause for concern.

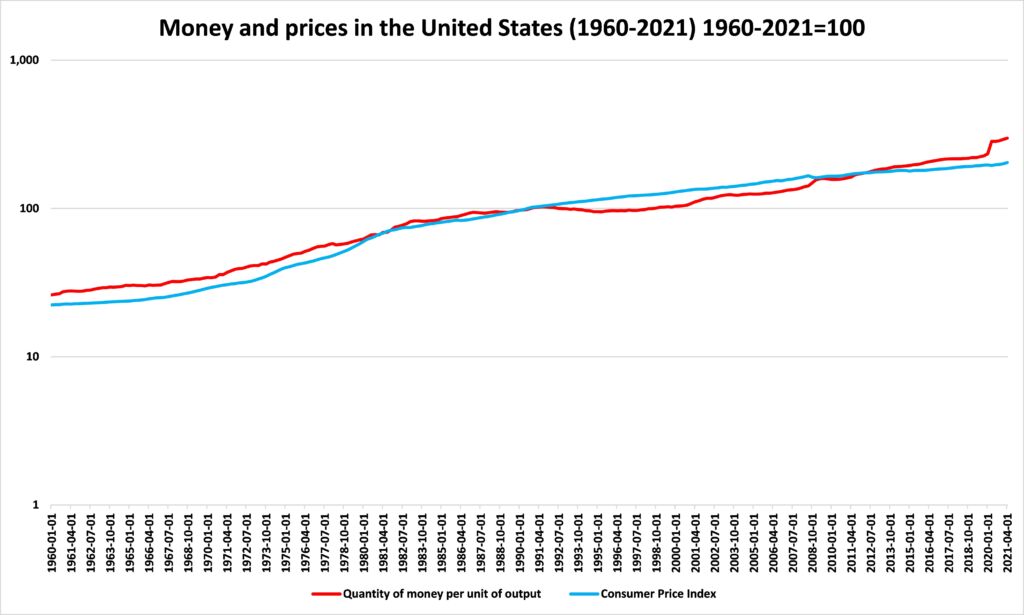

Figure 6 recreates and extends Figure 1. Using the method Friedman outlined in his book Money Mischief, it divides the figure for the M2 measure of the money supply by the figure for Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to derive Quantity of money per unit of output. The other line is the CPI, a measure of inflation. Both series are expressed as percentages of their average values over the period as whole to make them comparable and the Y axis is logarithmic.

Figure 6

Source: Center of the American Experiment

We see a fairly close relationship between the two series over an extended period of time, with a stark divergence in the last 18 months. This divergence is driven by a sharp increase in the Quantity of money per unit of output. This, in turn, is driven by an increase in the M2 measure of the money supply – the M2 money supply increased by 35 percent between January 2020 and August 2021 while real GDP grew by just 2 percent between Q1 2020 and Q2 2021.

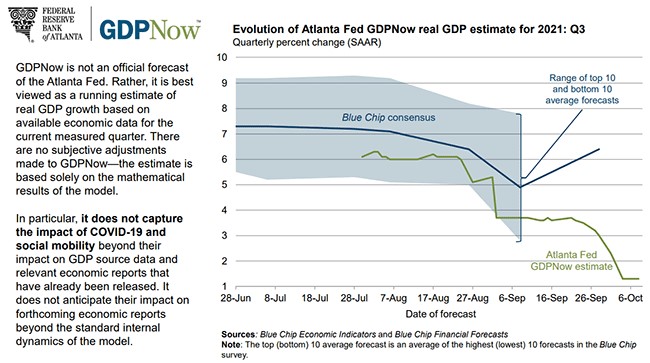

To bring these two lines back together, either the Quantity of money per unit of output has to fall or the CPI has to rise, which means more inflation. Given that the money isn’t going to disappear, for the Quantity of money divided by real GDP to fall, real GDP will need to grow at an impressive rate. So, the news that the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker has downgraded its forecast for Q3 GDP growth again is concerning. As Figure 7 shows, this forecast has dropped from 6 percent at the end of July to 1.3 percent now.

Figure 7

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

This suggests that the gap between these two lines isn’t going to close by the red line falling. So, it will be closed by the blue line rising – more inflation. If Milton Friedman was correct when he said that “inflation is primarily…produced by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output,” then the current elevated levels of inflation should be no surprise. Indeed, without rapid Real GDP growth, we could be in for a good deal more. Our current inflation might not be so transitory after all.