Minnesota’s unemployment rate soars to 8.1 percent

In recent weeks, I have been using numbers from Minnesota’s Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED) to track the collapse of employment in our state. As of today, 697,391 Minnesotans have filed for unemployment insurance since March 16th.

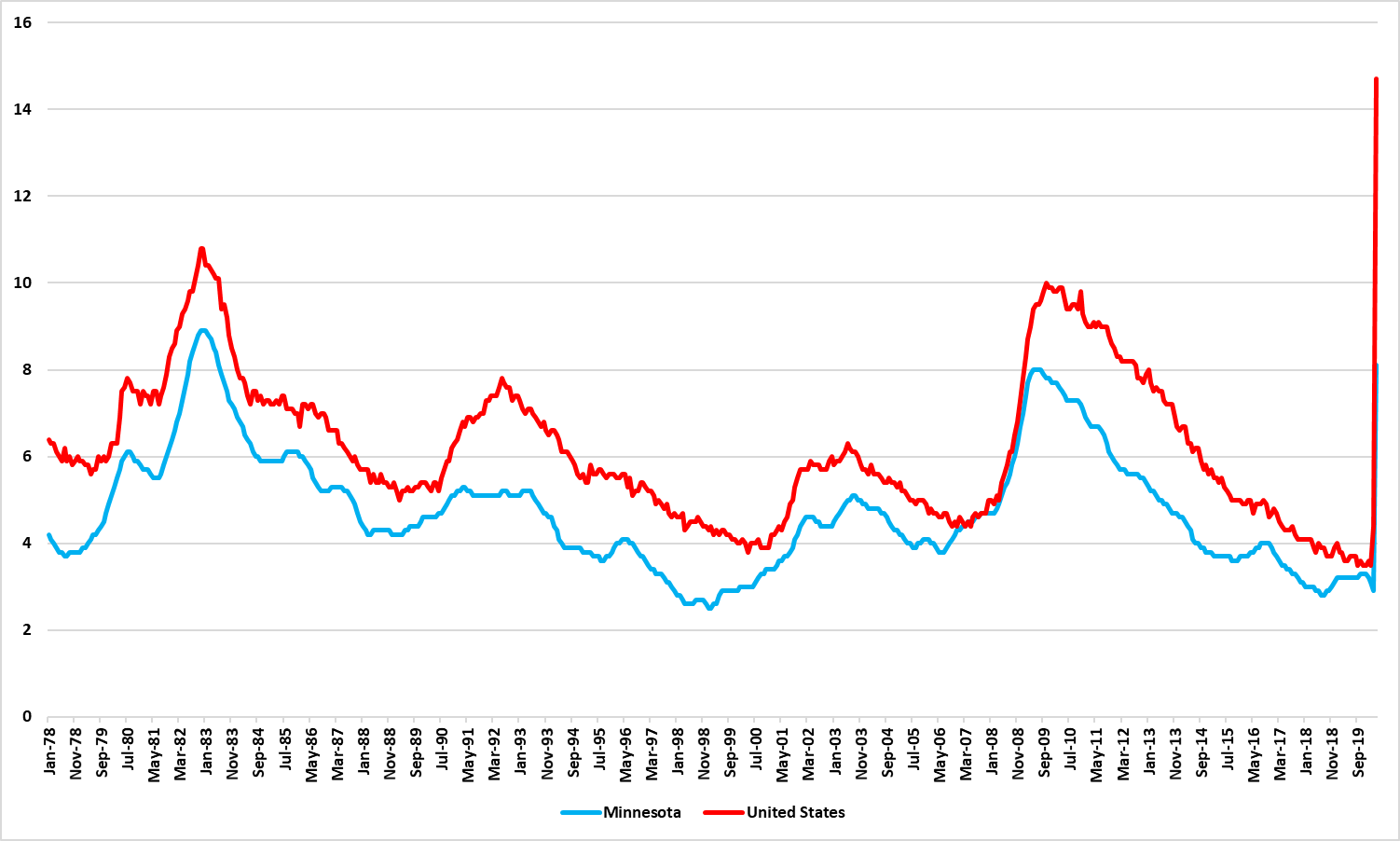

We now know what this looks like in the official unemployment numbers. Yesterday, DEED released numbers showing that the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate rose to 8.1% in April. As Figure 1 shows, this is higher than the peak of the Great Recession, 8.0% from May to August 2009, and is only a little below the previous peak, 8.9% between November 1983 and January 1983.

One of the unique things about this peak is how suddenly it has come. In the early 1980s, it took seventeen months from July 1981 to reach the peak in November 1983. In the Great Recession, it was thirty-five months from July 2006 to May 2009. According to DEED, in March 2020, Minnesota’s unemployment rate was 2.9%. The number of unemployed Minnesotans rose by 160,627 in one month.

Figure 1: Seasonally adjusted unemployment rate, %

Source: Department of Employment and Economic Development

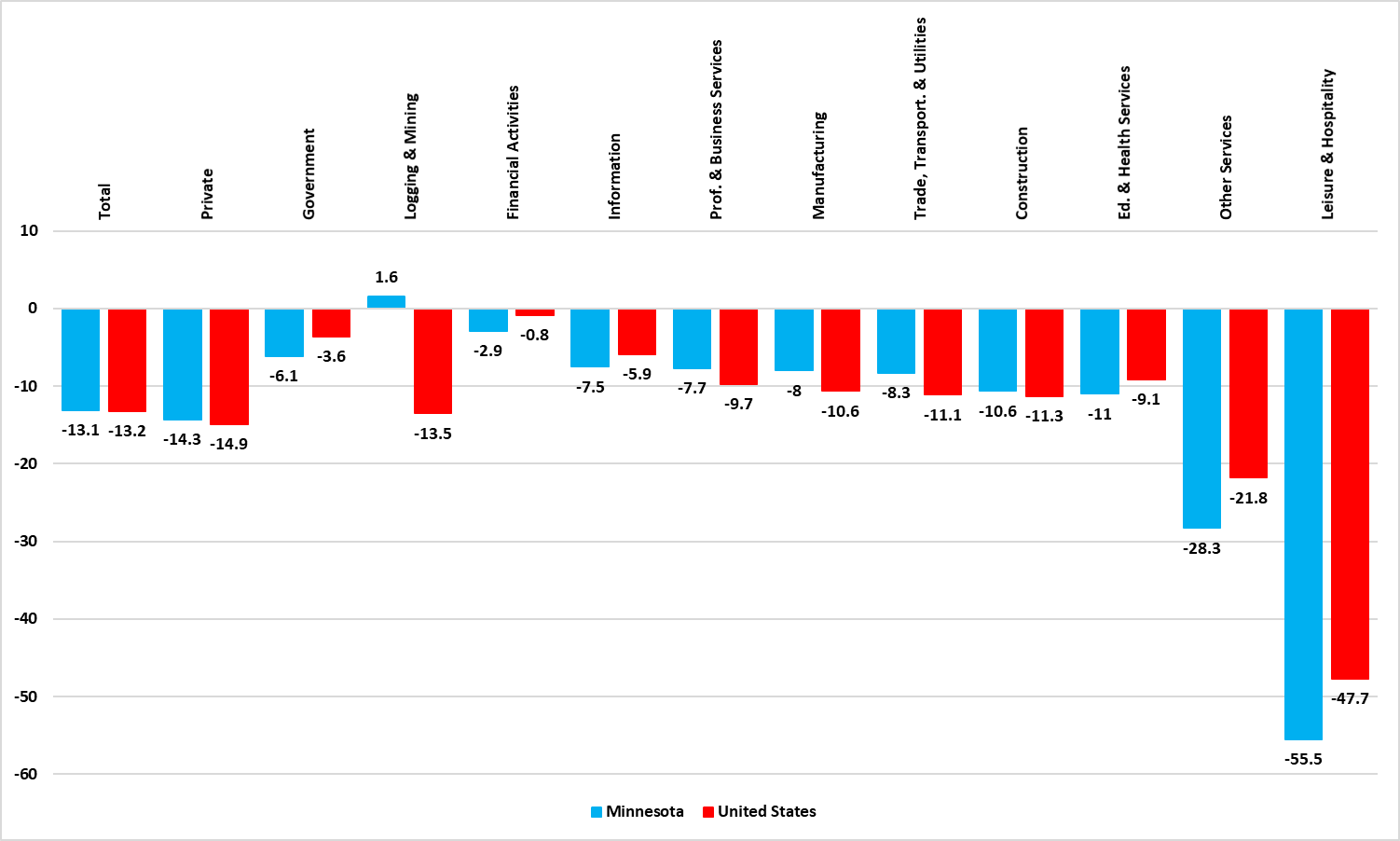

Figure 2 shows how employment in the various sectors of the national and Minnesota economy have been impacted. The hardest hit sector by far, both here and across the United States, is Leisure & Hospitality where employment is down 55.5% from this time last year – a loss of 148,593 jobs in Minnesota.

Figure 2: Over the year employment change, %

Source: Department of Employment and Economic Development

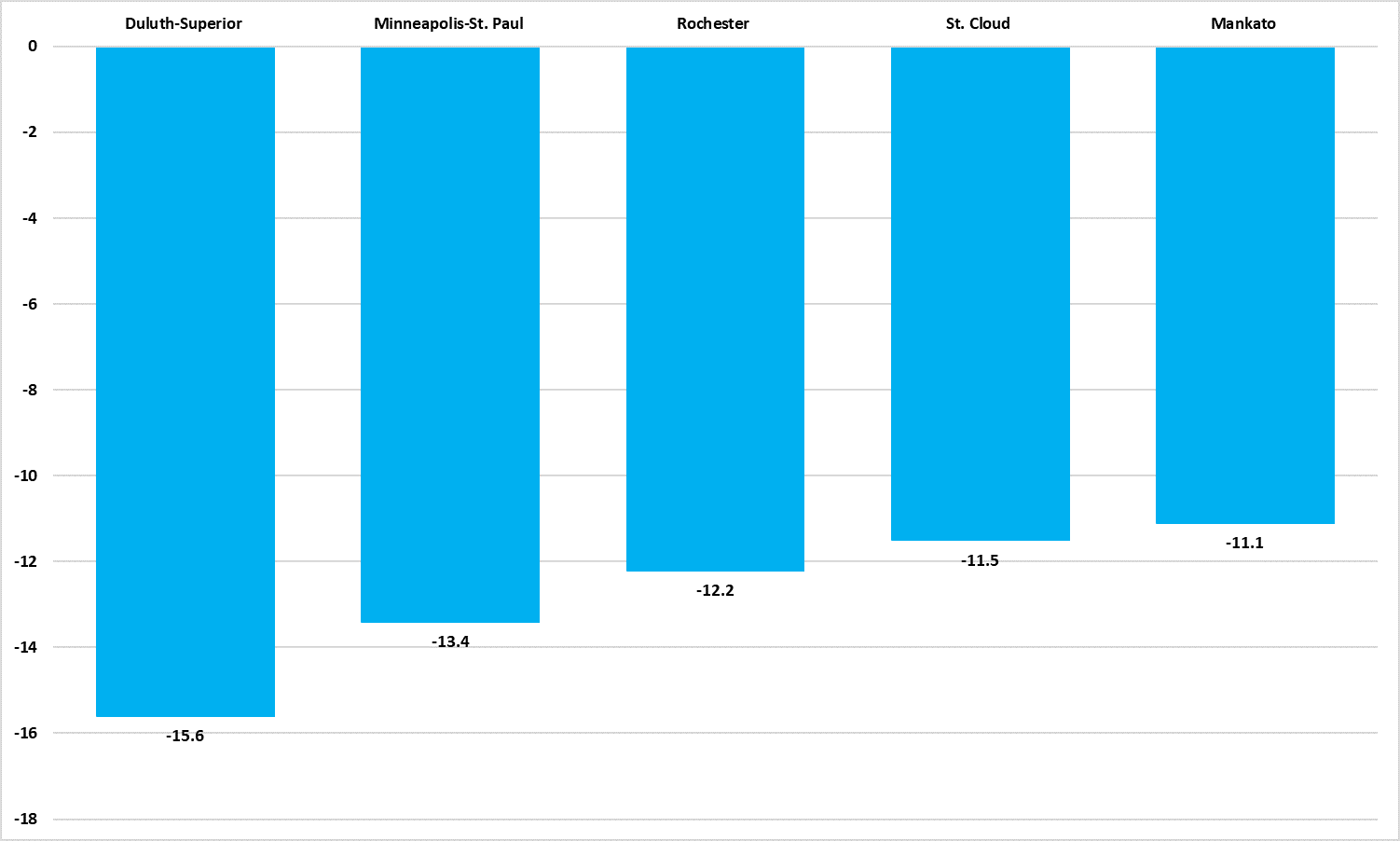

Figure 3 shows how employment in Minnesota’s five Metropolitan Statistical Areas has changed from April 2019 to April 2020. Employment is down sharply in all of them with Duluth being the hardest hit.

Figure 3: Over the year employment change, %

Source: Department of Employment and Economic Development

These numbers are horrific. And it is worth noting that the unemployment rate counts those who are unemployed and looking for work, ie have searched in the last month. Many newly unemployed workers are not looking for a new job in expectation of their previous one returning when the economy reopens. As this goes on, they will drop out of the labor force entirely. This might have the perverse effect of lowering the unemployment rate.

Either way, these numbers show that, while remaining vigilant in our fight against Covid-19, we need to find ways to get Minnesotans back to work.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.