Over 100,000 workers are still missing from the childcare industry

Even before the pandemic, high-quality affordable childcare was hard to come by. One of the reasons for that was the fact providers could not find qualified workers to take care of children.

Unfortunately, the pandemic has only worsened the problem.

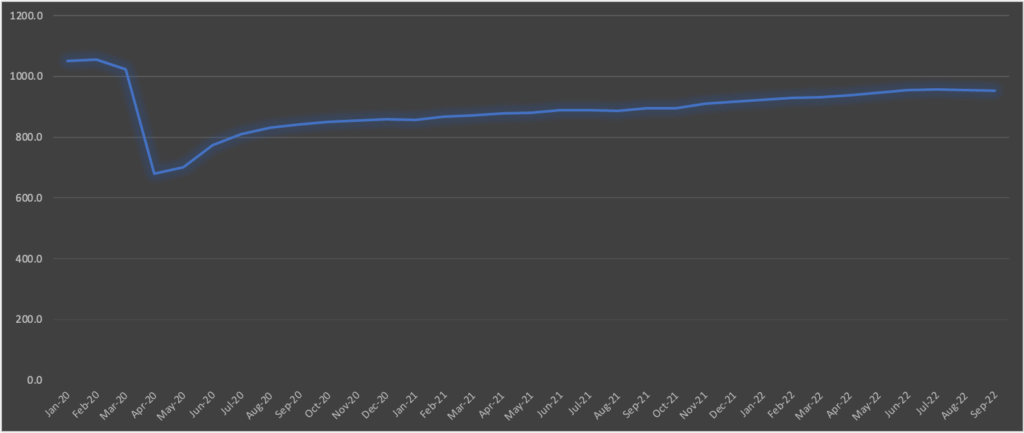

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), when employment peaked in February 2020, the childcare industry had about 1.054 million workers, nationally. That figure dipped below 700,000 when pandemic job losses peaked in April 2020. While some workers have returned, over 100,000 — about 10 percent of the pre-pandemic workforce — are not yet back.

Figure: Employment in the child day care services industry, January 2020 – September 2022

How childcare compares to the rest of the economy

Generally, the entire economy has gained all jobs lost, and total non-farm employment is above pre-pandemic levels — at least nationally. The same is true for most industries. Only a few industries are still yet to recover lost jobs. These include Leisure and hospitality, Mining and logging, Government, and Other (unspecified) services.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics records childcare employment as part of the Education and health services industry. And employment in this industry is 47,000 above its pre-pandemic levels. So, while in comparison with the rest of the economy, the childcare industry is not facing an exceptional issue, that is not the case when compared to its industry counterparts.

Table: Employment by industry, (Thousands)

| Industry | Feb-20 | Sep-22 | Difference |

| Total Non-farm | 152,504 | 153,018 | 514 |

| Mining and logging | 686 | 633 | (53) |

| Construction | 7,624 | 7,719 | 95 |

| Manufacturing | 12,785 | 12,880 | 95 |

| Trade, Transportation, and Utilities | 27,832 | 28,822 | 990 |

| Information | 2,903 | 3,043 | 140 |

| Financial activities | 8,870 | 8,957 | 87 |

| Professional and Business Services | 21,393 | 22,473 | 1,080 |

| Education and health services | 24,598 | 24,645 | 47 |

| Leisure and Hospitality | 16,983 | 15,845 | (1,138) |

| Other Services | 5,951 | 5,719 | (232) |

| Government | 22,879 | 22,282 | (597) |

Low wages and strict regulations to blame

So, why is the childcare industry losing workers while at the same time also failing to attract new entrants? Low wages and strict regulations are to blame. As the New York Times explains,

The typical American child-care worker earns about $13 per hour, and many earn just above minimum wage. Last year, 29 percent were so poor that they experienced food insecurity, according to a survey conducted by researchers at the University of Oregon.

Positions stocking shelves at Target, ringing up groceries at Trader Joe’s, and packing and loading boxes at Amazon warehouses now often pay more than jobs in child-care programs in many parts of the country. Working at a nail salon or managing pharmacy benefits over the phone can also lead to higher earnings.

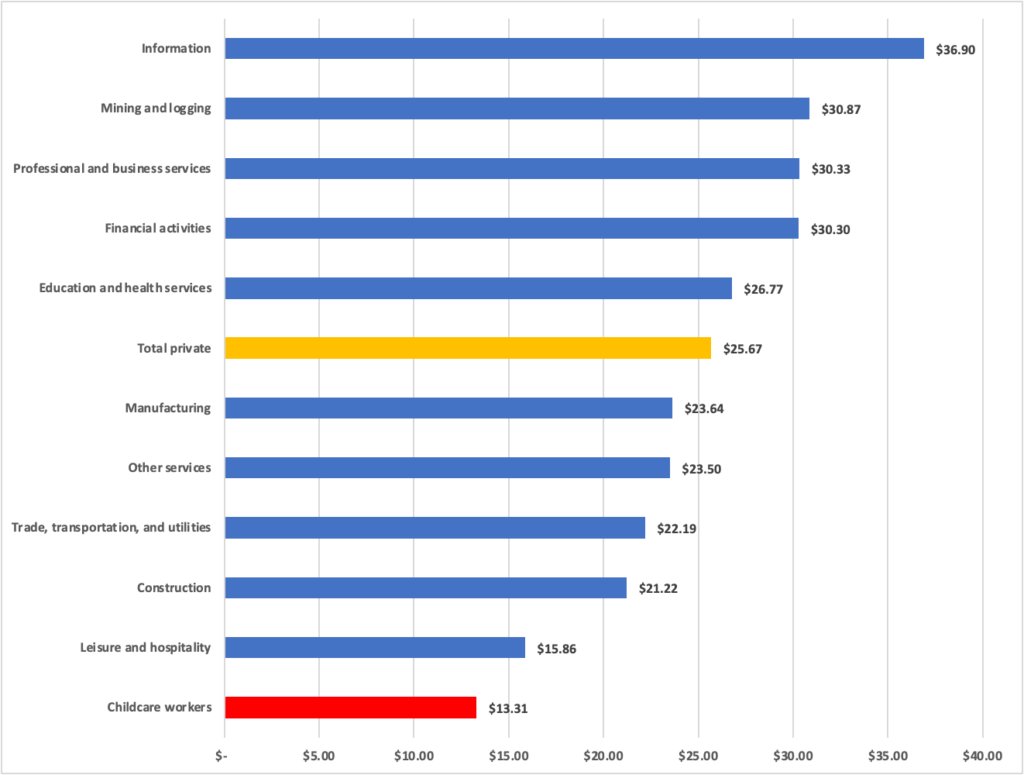

Indeed, as of May 2021 — the most recent date for which the BLS has data — childcare workers earned $13.31. In comparison, the average per-hour wage in the education and health services industry was nearly $27. And for the whole private sector, the average per-hour wage was almost $26. The only other industry that has such similarly low wages as childcare is the leisure and hospitality industry, and it has also lost over 1 million of its workers between February 2020 and September 2022.

In fact, out of all the private sector industries that have lost jobs, mining and logging is the only one with above-average wages. The Mining and logging industry has, however, been losing jobs consistently before the pandemic, which could explain the industry’s slow recovery — or lack thereof.

Figure: Average hourly wage by industry, May 2021

But in addition to low wages, the childcare industry is also especially less competitive because of its stringent rules. Ringing up groceries and packing groceries, for example, are jobs that do not have strict qualification requirements. On the other hand, childcare work requires professional credentials and years of experience, yet it pays lower than these other jobs.

In Minnesota, for example, to be a childcare worker, someone with a high school degree has to have over six thousand hours of experience and some college credits to take care of children. Not to mention that a childcare worker applicant often has to go through a rigorous process to start a job, often involving fingerprinting and an enhanced background check, while at other jobs, the process is much easier.

It is no wonder childcare workers are leaving the industry in droves.