Proposals for feasible tax reform

Last week, we released our new paper ‘The State of Minnesota’s Economy: 2020‘. In it, we argued that Minnesota’s economy is being held back by its excessively high taxes. Chief among these are the individual income tax and corporate income tax. Since 2020, Minnesota has slipped a place, to 46th, on the Tax Foundation’s 2021 State Business Tax Climate Index. This was largely driven by our state’s high corporate tax rates – where we rank 6th highest in the United States – and our individual taxes, where we rank 5th highest. To make serious progress up these rankings, we need to see these rates come down.

But there are other things dragging Minnesota down on these rankings which would help us climb them if remedied. They are not huge changes such as cutting our corporate and income tax rates would be, but they could draw bipartisan support and would move us in the right direction.

1) CONFORM TO THE FEDERAL DEPLETION SCHEDULE

Two of these measures would be to reform Minnesota’s corporate tax base.

For example, our state is one of thirteen that doesn’t fully conform to the federal system for the deduction for depletion. This works like depreciation but applies to natural resources. By imposing its own schedule, Minnesota makes its tax system is more complex than it need be. Conforming to the federal schedule would help this.

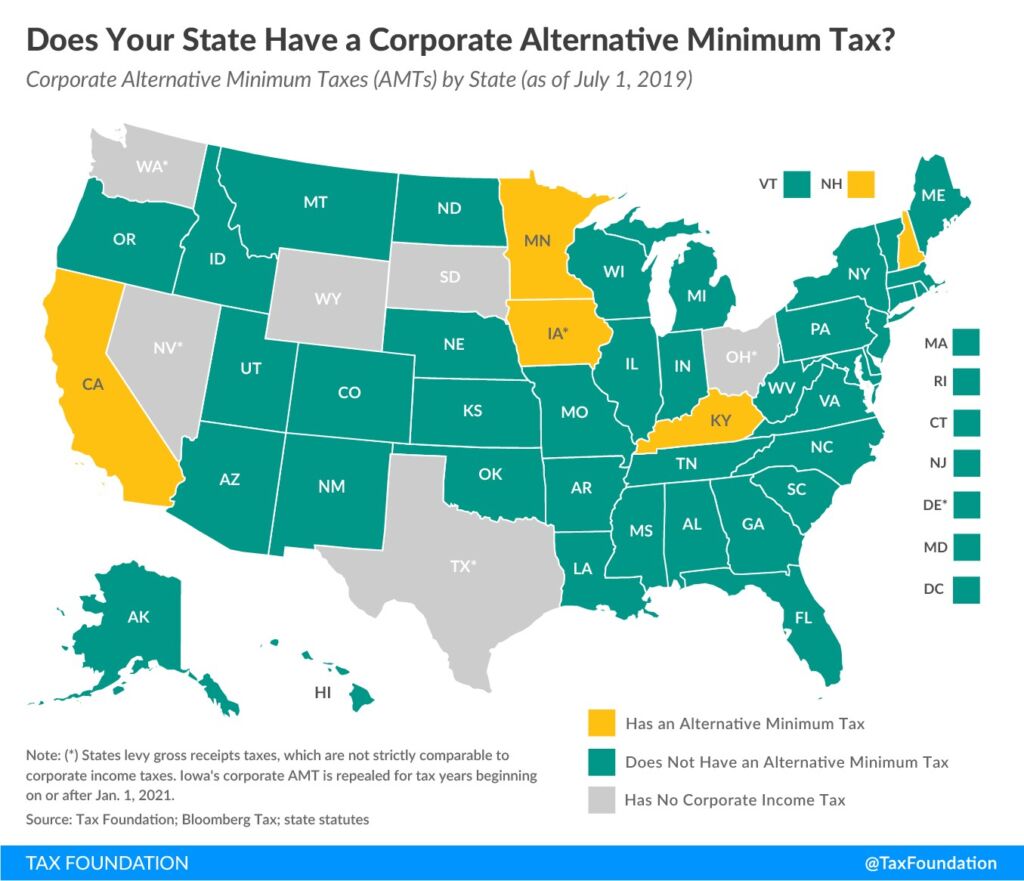

2) ELIMINATE MINNESOTA’S ALTERNATIVE MINIMUM TAX FOR CORPORATIONS

Another would be to ditch its alternative minimum tax (AMT) for corporations, something we at the Center have long argued for. These corporate AMTs exist to prevent corporations from reducing their corporate income tax liability beyond a certain level, and Minnesota is one of only five states – down from eight as recently as 2017 – which imposes one. According to the Tax Foundation:

The corporate AMT is an inefficient means of ensuring taxpayers pay a minimum level of taxes each year, a factor which contributed to its repeal in several states and on the federal level. By requiring taxpayers to calculate their tax liability under two different systems, the federal AMT imposed steep compliance costs on businesses, which in some cases proved larger than collections. States that have not yet repealed their AMTs ought to consider whether the relatively small amount of additional revenue they gain from corporate AMTs is worth the added complexity of maintaining two parallel tax systems, and whether one streamlined corporate tax code with fewer deductions is a more efficient means of meeting annual revenue targets.

As the Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence puts it:

With the federal repeal of the AMT and various modifications throughout the Internal Revenue Code, the Minnesota AMT would be even more complicated and burdensome and certainly no picnic for the Department to audit. While waiting on the Department’s revenue estimate for the cost of this proposal, it’s worth noting the last time they published a corporate income tax bulletin (about a decade ago) the corporate AMT constituted about 1% of state corporate income tax collections. Given the current circumstances, that’s not worth retaining.

A bill to repeal Minnesota’s corporate AMT was proposed by Ann Rest (DFL) and passed in 2018, but was a casualty of one of then Governor Mark Dayton’s tantrums, when he vetoed the tax bill.

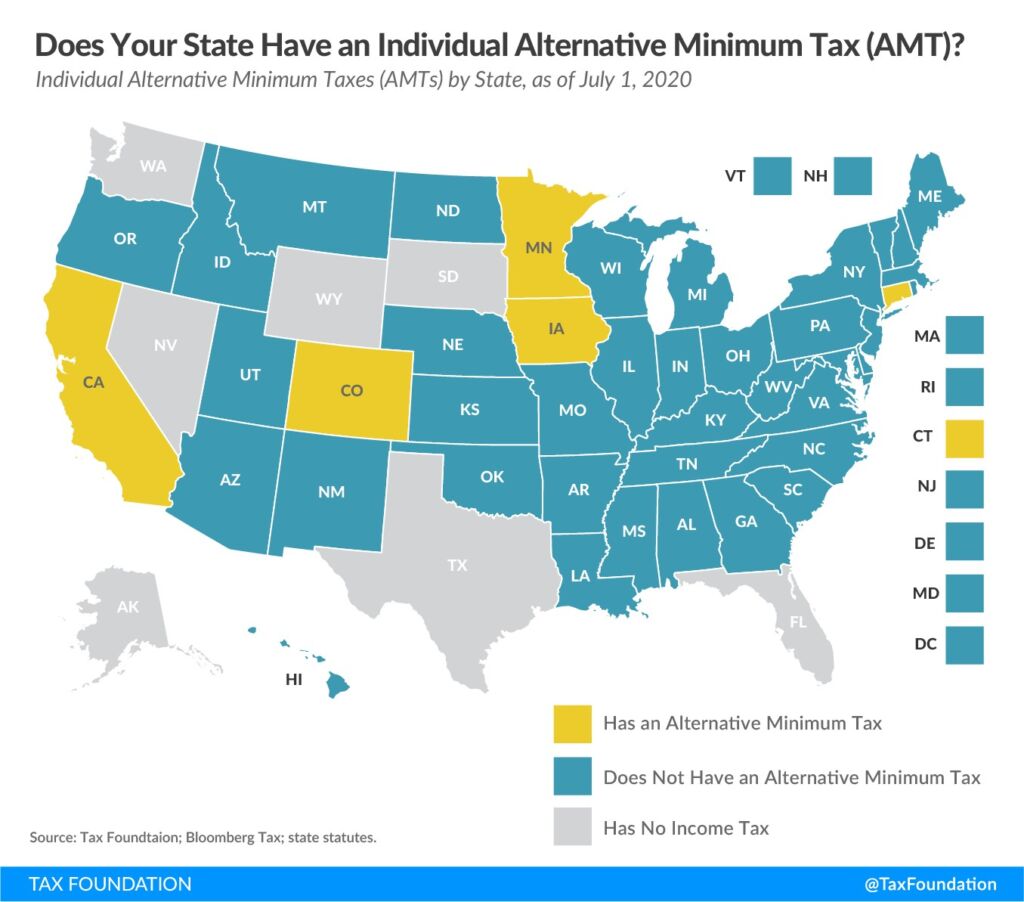

3) ABOLISH MINNESOTA’S ALTERNATIVE MINIMUM TAX FOR INDIVIDUALS

The next two measures would improve Minnesota’s individual income tax base.

One of these would be to abolish the state’s alternative minimum tax (AMT) for individuals. Minnesota is one of just five states that imposes an individual AMT. According to the Tax Foundation:

At the federal level, the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) was created in 1969 to ensure that all taxpayers paid some minimum level of taxes every year. Unfortunately, it does so by creating a parallel tax system to the standard individual income tax code. AMTs are an inefficient way to prevent tax deductions and credits from totally eliminating tax liability. As such, states that have mimicked the federal AMT put themselves at a competitive disadvantage through needless tax complexity.

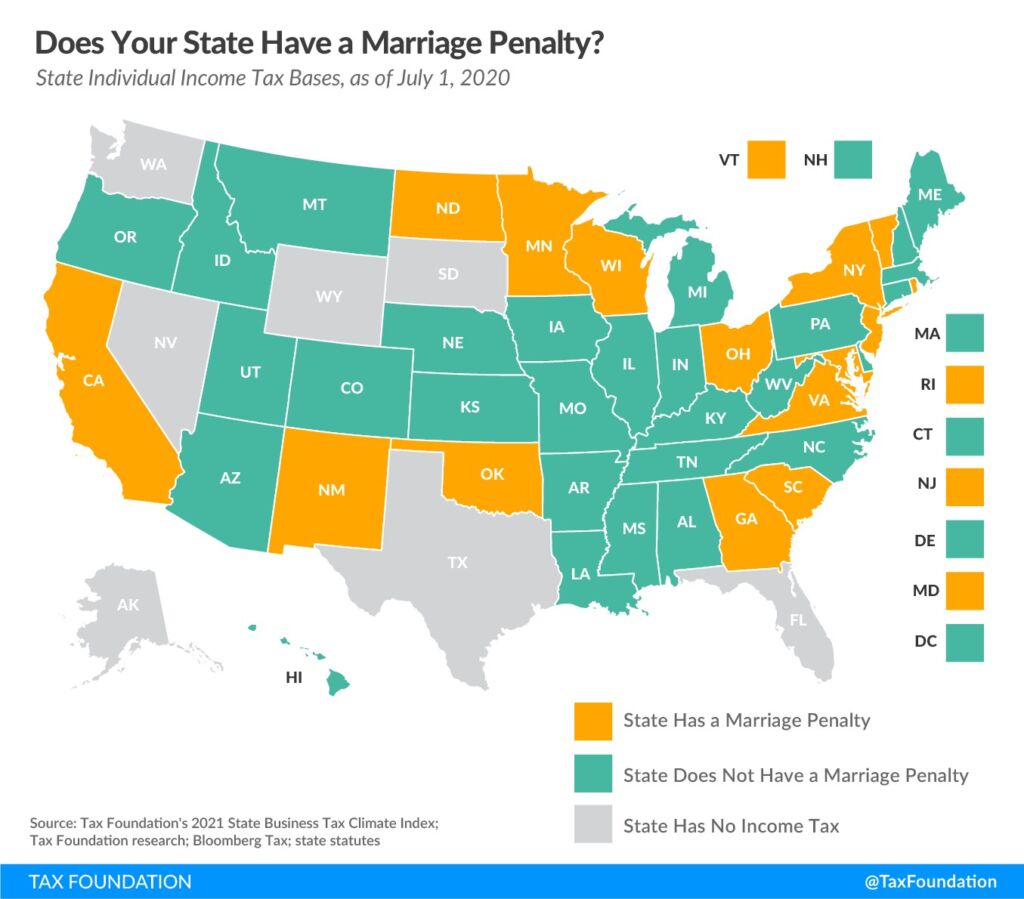

4) ELIMINATE THE STATE’S MARRIAGE TAX PENALTY

A second measure would be to eliminate Minnesota’s marriage tax penalty. Minnesota is one of twenty-three states and the District of Columbia to have these penalties built into their tax codes. As the Tax Foundation explains:

A marriage penalty exists when a state’s standard deduction and tax brackets for married taxpayers filing jointly are not double those for single filers. As a result, two singles (if combined) can have a lower tax bill than a married couple filing jointly with the same income. This is discriminatory and has serious business ramifications. The top-earning 20 percent of taxpayers is dominated (85 percent) by married couples. This same 20 percent also has the highest concentration of business owners of all income groups (Hodge 2003A, Hodge 2003B). Because of these concentrations, marriage penalties have the potential to affect a significant share of pass-through businesses.

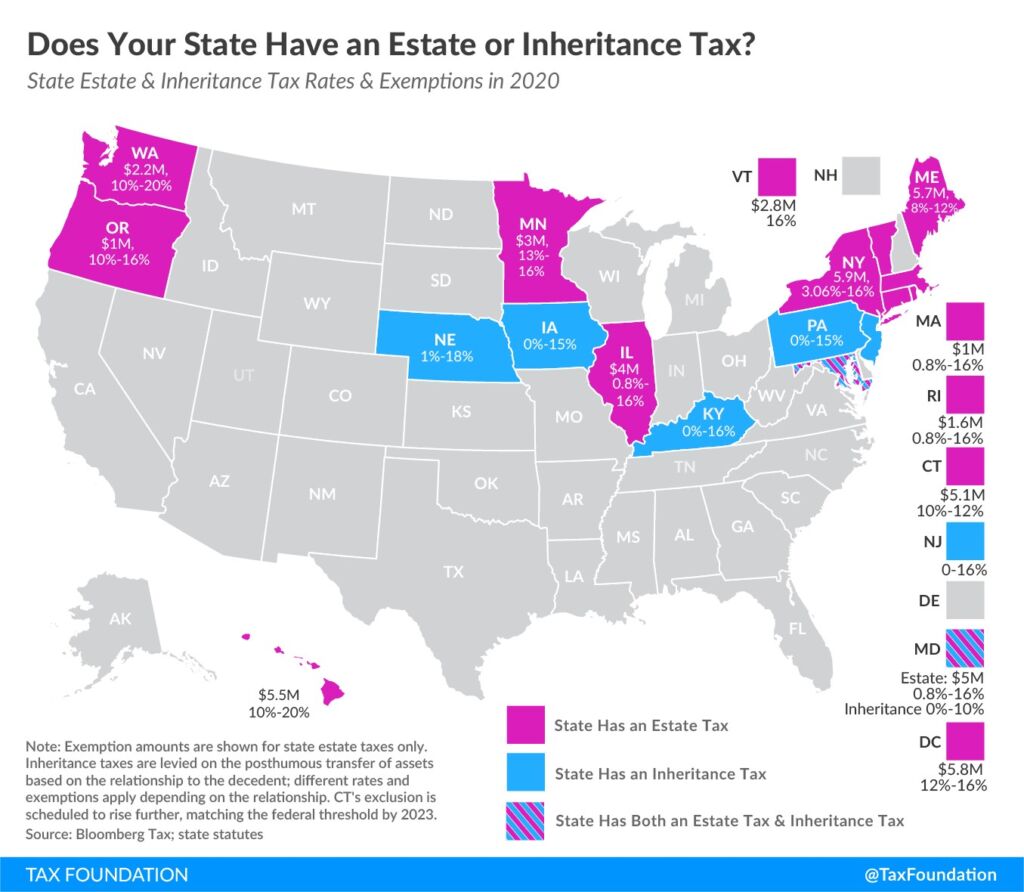

5) ABOLISH MINNESOTA’S ESTATE TAX

Finally, a fifth measure would reform Minnesota’s property tax base.

This would be to abolish the state’s estate tax. Minnesota is one of twelve states and the District of Columbia to impose estate taxes and a further six impose inheritance taxes. According to the Tax Foundation:

Estate and inheritance taxes are burdensome. They disincentivize business investment and can drive high-net-worth individuals out-of-state. They also yield estate planning and tax avoidance strategies that are inefficient, not only for affected taxpayers, but for the economy at large. The handful of states that still impose them should consider eliminating them or at least conforming to federal exemption levels.

The point about driving high-net-worth individuals out of the state is crucial in the context of Minnesota’s looming budget deficit. As I wrote in our report The Cost of Minnesota’s Estate Tax, Minnesota taxes estates more heavily than most states. Seven of the states that levy an estate tax and the District of Columbia have a higher exemption. The state’s starting rate of estate taxation—13.0%—is higher than any of the other jurisdictions that levy one. Its top rate is 16.0%. Only the state of Washington and Hawaii have a higher top rate.

As I’ve written before:

When taxes are high in one jurisdiction, people have an incentive to move to another one with lower taxes. We see people doing just this. The large and growing body of evidence on the effects of taxation on migration was summarized recently by economists Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais, Mathilde Muñoz, and Stefanie Stantcheva. They found that, “There is growing evidence that taxes can affect the geographic location of people both within and across countries. This migration channel creates another efficiency cost of taxation that policy makers need to contend with when setting tax policy.”

…

There is evidence that Minnesotans leave the state in response to these taxes. In 2013, the Minnesota Society of Certified Public Accountants surveyed its members and found that “more than 86 percent of respondents said clients had asked for advice regarding residency options and moving from Minnesota;” 91% said the number of clients asking about moving had increased from previous years.

When these people move, they take with them the future payments of income and sales taxes, among others. From the point of view of state government tax revenues, the question is whether the amount the estate tax brings in from those who stay is high enough to more than offset the lost revenues from these other taxes from those who go.We found they probably aren’t. We estimated that, in 2015-2016 for example, the estate tax cost the state government $232.5 million in lost income and sales tax revenues.

A subsequent paper by economists Enrico Moretti and Daniel J. Wilson confirmed this:

In their paper, Moretti and Wilson studied “the effect of state-level estate taxes on the geographical location of the Forbes 400 richest Americans.” They then “estimate(d) the effect of billionaire deaths on state tax revenues.” “Surprisingly,” they concluded, “we find that the benefit exceeds the cost for the vast majority of states.”

But not for Minnesota. We are one of four states identified by Moretti and Wilson where the costs in terms of lost revenues from other taxes outweigh the benefits in terms of estate tax revenues. Those states are, coincidentally, the ones with the highest top rates of income tax: Hawaii, Minnesota, Oregon, and Vermont.

The purpose of taxation is not to bash the rich but to raise revenue to pay for government functions. Minnesota’s estate tax, by costing the state government revenue, actually makes this harder. Our estate tax should be repealed.

The Tax Foundation calculates that, taken together, these five measures would raise Minnesota from 46th to 40th overall on their State Business Tax Climate Index. Of course, we would like to be higher, but it would be a definite step in the right direction.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.