Relative to the share of the state’s income they earn, ‘the rich’ in Minnesota are taxed disproportionately heavily and have been for years

As Gov. Walz tries to close a budget deficit which is soon to disappear anyway with higher taxes on ‘the rich’ which will actually fall on people other than the ‘the rich’, the question of how much tax ‘the rich’ ought to pay is once again to the fore.

Positive and normative economics

The economist Milton Friedman famously noted that there are ‘positive’ questions in economics and ‘normative’ ones. A positive question (in theory) permits of a definite, objective answer, such as ‘What will happen to employment if the minimum wage is hiked?’ A normative question is subjective, such as ‘Should we hike the minimum wage?’

To a large extent, the question of how much tax ‘the rich’ ought to pay is a normative question. You might think that each person should pay the same amount of tax: a poll tax. You might think that each person should pay the same share of their income in tax: a flat tax. Or, you might think that people who earn more should pay a higher share of their income in tax: a progressive tax. No one of these is ‘correct’. I have my opinion, but yours could be very different. There is no way to say, objectively, which formula gives you the ‘correct’ answer to how much tax ‘the rich’ ought to pay.

How much tax do ‘the rich’ pay?

We can bring clarity to normative debates, however, with objective facts. The question ‘How much tax do the top 10 percent of households by income pay?’ is, for example, a positive question. The Minnesota Department of Revenue collects such data and publishes it in its Tax Incidence Studies. Using the most recent of these, I noted recently that:

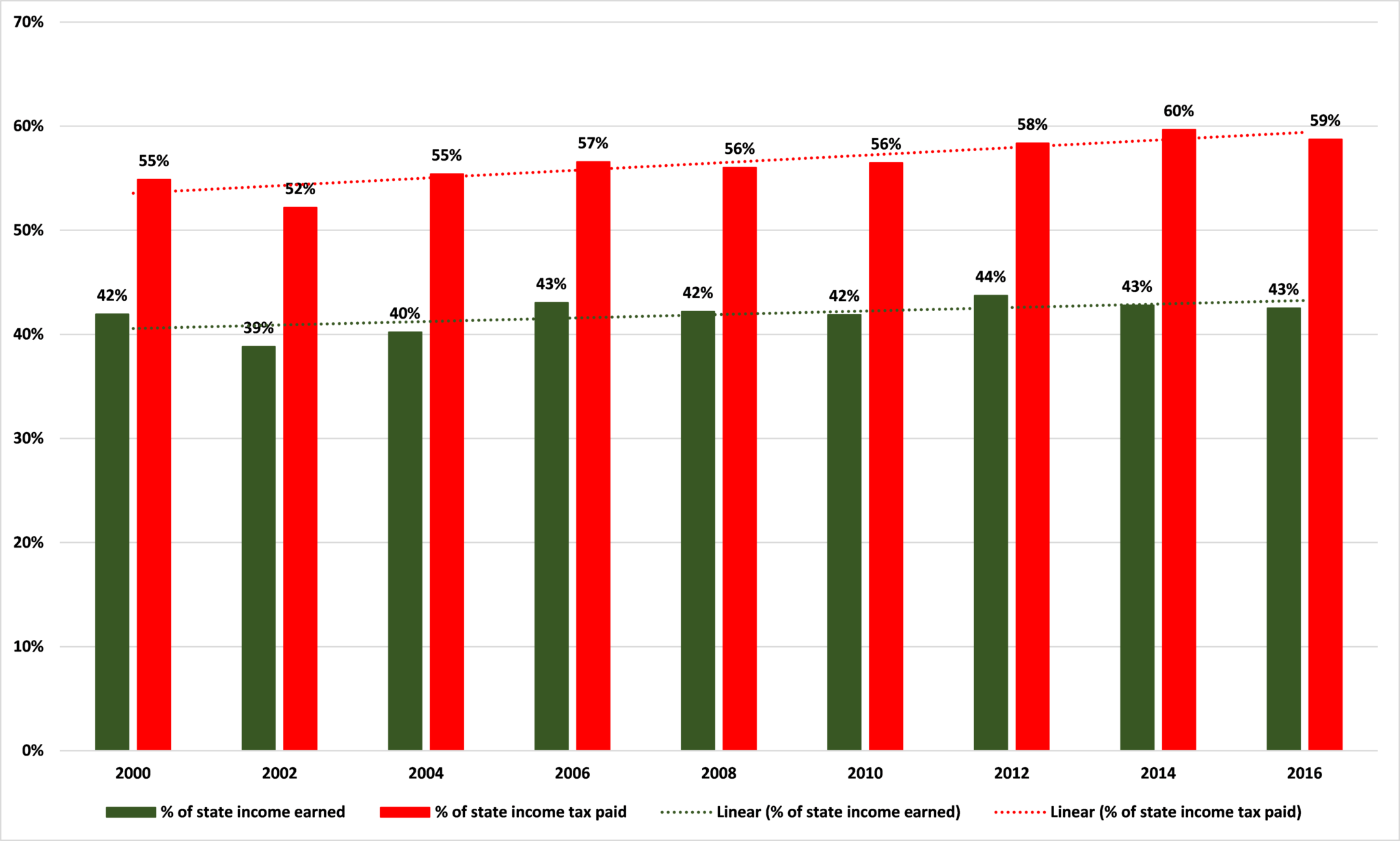

The bottom 30% of Minnesota households [by income] earn 6% of the state’s total income but pay 0% of its individual income taxes (technically -0.5%, they receive $56 million in tax credits). Households in the top 10% of incomes, however, those earning over $156,101, earn 43% of all the state’s income but pay 59% of its total individual income taxes.

We can say from this that ‘the rich’ in Minnesota, as defined by being in the top 10% of households by income:

…earn a disproportionate share of state income but pay an amount of state income tax which is more disproportionate even than that.

Assuming that the Department of Revenue’s data is correct, both of these statements are also correct. But whether this means that ‘the rich’ are being taxed too heavily is a normative question to which different people will have different answers.

Keeping sight of such facts can help to address normative questions by helping us spot when someone is saying something that is not true. Take, for example, the statement that:

The top’s growing share of total taxes only reflects the fact that they are receiving a larger and larger share of total income.

If we define ‘the top’ as the top 10 percent of households by income, we can look at the Tax Incidence Studies to see how their share of the state’s total income has changed over time. As Figure 1 shows, those at the top are not, in fact, receiving “a larger and larger share of total income” – that is just false. Their share of total income edged by one percentage point, from 42 percent to 43 percent between 2000 and 2016. It follows that if those at the top are not receiving a larger and larger share of total income, this cannot be responsible for their “growing share of total taxes”, a share which, in any case, hasn’t risen all that much: by four percentage points, from 55 percent to 59 percent, between 2000 and 2016. So, while it is objectively true that ‘the rich’ in Minnesota are taxed disproportionately heavily relative to their share of income, it also objectively true that this has been the case since at least 2000. We can say that that statement is nonsense with no grounding in fact.

Figure 1: Share of state’s income earned and income taxes paid by the top 10% of Minnesota households by income

Source: Department of Revenue

Analyzing the data like this shows us that we can discount an argument for higher taxes based on the notion that ‘the rich’ are earning a vastly greater share of income earned in Minnesota. By applying this technique to spot untruths like the one contained in that statement, we can have a better standard of debate, even if the normative answers remain as slippery as ever.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.