Serious crimes soar even higher on Metro Transit in 2023

It’s hard to believe the threat to passenger safety on Twin Cities light rail and bus lines could get any worse than the 50 percent increase in crime on Metro Transit in 2022. But the crime statistics just released for the first quarter of 2022 show security on the transit system continues to deteriorate with no end in sight.

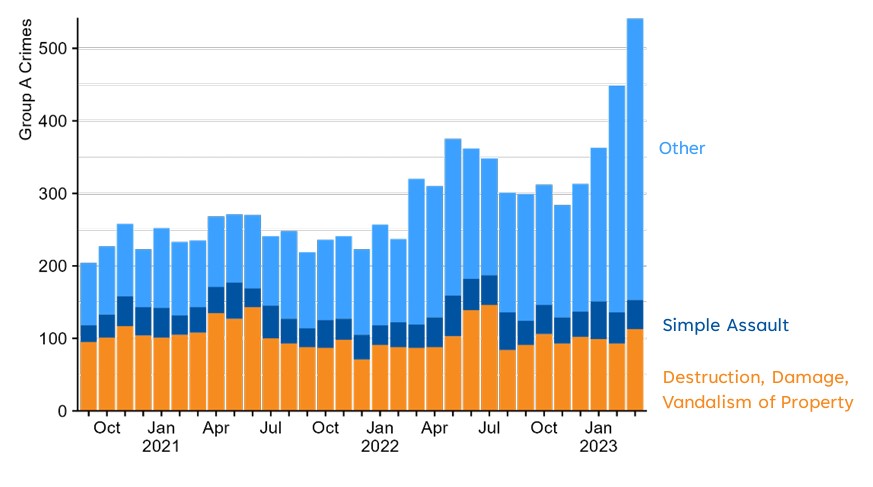

At the Met Council’s quarterly updates, it’s no longer a matter of whether Metro Transit crime has gotten worse, but rather how much worse. The latest numbers show that serious crime on metro light rail and bus lines has shot up by two-thirds year over year, from 817 crimes in 2022 to 1,352 crimes through March of this year.

Newly installed Metro Transit police chief Ernest Morales III was put in the awkward position of defending the agency’s latest setback at his first Met Council presentation, covered by the Star Tribune.

“We want to take the system back for our customers,” Morales said Wednesday during a Metropolitan Council meeting.

The need to combat crime has become especially acute as ridership slowly recovers following the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Metro Transit, the crime increase is largely driven by drug use and drug-equipment violations, which accounted for 38% of serious crimes on public transit.

The Met Council launched a 40-point public transit safety plan last year calling for more police officers, private security teams and a focus on transit stations that serve as hubs for drug addicts, vagrants and criminals. But serious crimes continue to proliferate, a deterrent to convincing passengers to return to public transit post-pandemic.

Morales, who has spent considerable time aboard trains and buses over the past two months, said Metro Transit is “a major transportation system that has become an unofficial homeless shelter.” Because there are no turnstiles to discourage fare evaders, he said, “we’ve seen a flood of chemically dependent people.”

Morales’ acknowledgement of the lack of turnstiles at transit stations as a key reason for the system’s security problems may signal a new pragmatism in confronting the crime issue. The installation of turnstiles is a key recommendation of American Experiment’s recent “Off the Rails” report.

“The main reason light rail is so attractive to potential criminals is the lack of rigorous fare enforcement. The solution is to put fences and turnstiles around every light-rail stop and not allow people inside unless they have paid their fares.”

Transit ridership has increased this year, but remains well below 2019 levels. One of the community representatives involved in the effort to regain control of the system told KSTP-TV that even his family members feel threatened on public transit.

“It’s scary, and I have my kids, and other kids I mentor in the community, that often say they don’t often go places because they are scared to go on public transportation,” said Miki Frost.

Frost, a St. Paul youth mentor, is working with the Twin Cities Men’s Movement to help find and organize volunteers that plan to begin riding the light rail in the next month.

Organizers said they hope to improve safety and help those in need connect to resources for addition, housing, and employment.

But the agency’s new top cop knows it will take more than volunteers and agency representatives to clean up Metro Transit light rail cars and buses.

Morales said those who commit more serious crimes should be prosecuted: “We must hold people accountable for their behavior.”