The childcare crisis is not due to market failure

Usually, people who advocate for spending money on childcare are reluctant to consider free-market solutions to the childcare crisis. This is because such people believe that the childcare market exhibits what economists call “market failure.” In that case, the market cannot be relied upon to provide solutions.

On Tuesday, February 7, for example, the Committee on Children and Families Finance Policy heard from the Great Start for All Minnesota Children Task Force, which presented their proposals on how to improve access to high-quality affordable childcare in Minnesota. The Task Force, which called for significant spending on early childhood education, largely blamed the childcare crisis on market failure.

But does the childcare industry indeed suffer from market failure? A deep exploration shows that that’s not the case.

What is market failure?

In economics, a market failure exists when there are positive or negative externalities involved with the production of certain goods or services such that third parties also bare a proportion of the cost or benefit from such a transaction. A good example is pollution.

Usually, when a company pollutes — say by dumping harmful chemicals in a river — anyone who uses that river is negatively harmed. This is a negative externality. And usually with negative externalities, if the offending party is not made to pay for such an action, it overproduces, since it doesn’t bear the full cost of production.

Childcare is usually considered an example of a positive externality. Much like elementary or tertiary education, childcare provides a building block for kids to learn to become productive members of society. And when kids become productive members of society, everyone benefits.

With positive externalities, there is a tendency to underproduce, since market participants do not reap all the benefits from access to childcare since they spill over to a third party. This then leads to less-than-optimal production of childcare. The government, therefore, must invest and subsidize childcare in order for society to capture the full benefits.

This market failure shows up in these three ways

- Low wages for workers: Because workers subsidize parents who usually can’t afford to pay the true cost of care, they get low wages.

- Low supply of childcare, which forces parents — especially mothers — to leave the workforce and stay home with their children.

- Lack of high-quality childcare

Is the childcare crisis due to market failure?

Certainly, the economics of childcare is partly to blame for high costs and low pay.

Childcare suffers from what economists call Baumol’s cost disease. According to William Baumol, as workers become more productive due to advancements in technology, they tend to see their wages rise. However, childcare does not benefit from advancements in technology since it is a labor-intensive sector. Thereby, to keep workers from fleeing to other industries which are experiencing wage hikes due to productivity, the childcare sector must raise wages.

However, at the same time, parents are unable to pay higher tuition which would enable providers to pay their workers those higher wages. Ergo, the childcare industry is plagued with high prices, but low wages for workers.

However, this is something that is universal across states and across countries. It does not explain why childcare is less affordable in other states than in others. More importantly, it does not indicate that issues plaguing the childcare sector are due to market failure.

Low wages

Indeed, the childcare sector has low wages. And partly that is due to the fact that these low wages are used to subsidize tuition for parents. However, that does not necessarily mean market failure for two reasons.

Firstly, there are non-pecuniary benefits to caring for children. Workers in the childcare industry care more than about tier wages. They also like their jobs and they like taking care of their children. For that reason, they are able to compensate for these low wages with the fulfillment that they get from caring for children.

Secondly, a lot of research has shown that parents are unwilling to pay for high-quality childcare — which is more expensive. This might be because parents do not value high-quality childcare very highly. Or it could be because they realize that factors like staff-child ratios or group size limits do not necessarily constitute quality. Either way, the interactions between parents and childcare providers ultimately result in an equilibrium solution wherein workers accept lower wages to subsidize tuition — and each party benefits.

Research has shown that low teacher pay in childcare is actually due to regulation, and not necessarily because of the market. Strict regulations, like the staff-child ratios, group size limits, annual training requirements as well as hiring requirements raise the cost of providing care. But since parents are unwilling to pay for such higher costs, those costs then fall on workers.

Affordability

A lot of things affect the price of childcare. These include the type of care, the age of the child, and the economics of childcare. But then again, these factors are universal. Instead, what affects childcare prices is government regulation. States which have less affordable childcare tend to have stricter regulations than those with more affordable childcare, which is a sign that market failure is not to blame for high prices.

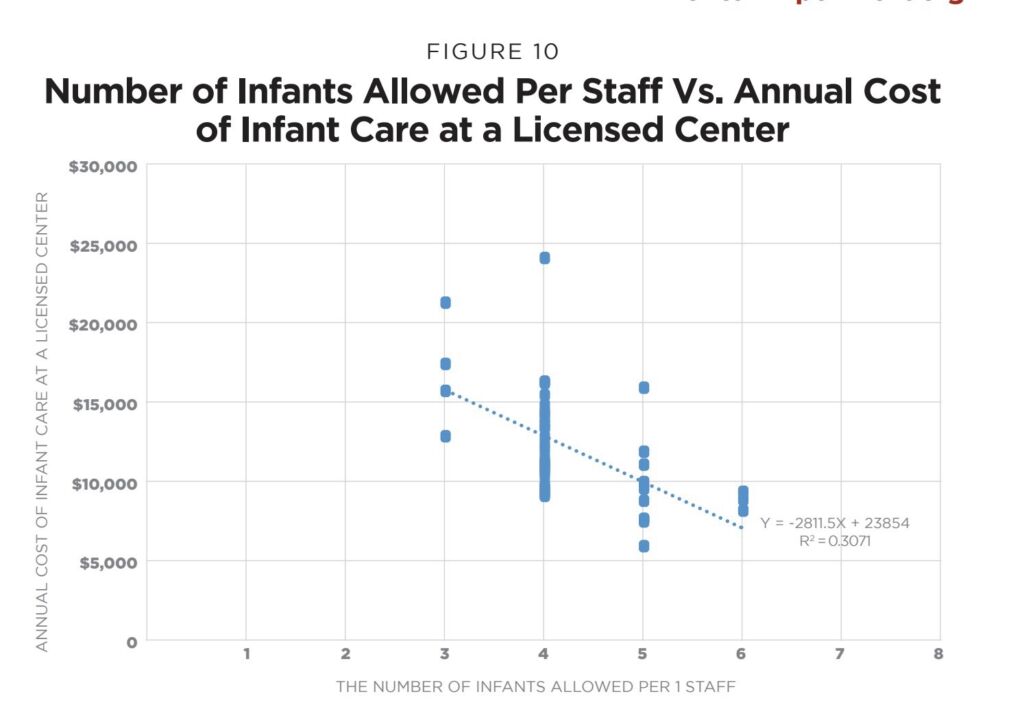

In a report published last year, for example, American Experiment found that if Minnesota were to loosen regulations and allow centers to have five infants per teacher, the cost of center-based infant care would go down by about $2,800.

But even if childcare prices were lower, it does not mean that every parent would work. The truth is that some parents prefer to stay home and provide childcare at home.

But even if parents stay home because they cannot afford childcare, that does not constitute market failure.

When a parent stays home with their kid, they give up their earnings. But if those earnings are less than what the parent would pay for the cost of childcare, then of course it makes economic sense for the parent to stay home and provide childcare at home. Otherwise, the family would be incurring a loss by sending their child to daycare for a job that pays lower than what that childcare costs. That is not only economical but also efficient for the economy.

Similarly, if taxpayers were on the hook for providing childcare, it would not make sense to subsidize childcare for a parent whose whole job is paying less than the total cost of childcare. That is a loss to the economy and an inefficient allocation of resources.

Quality

High-quality childcare can mean different things to different people. And quality in childcare by itself is hard to measure. But government agents usually tend to look at structural measures as a signal for quality. These include things like staff-child ratios, group size limits, annual training hours, and staff hiring requirements.

Evidence, however, indicates that these structural measures are hardly a measure of quality. These are merely inputs and do not necessarily have strong effects on quality.

Additionally, parents are just not willing to pay a higher price for smaller group sizes and higher staff ratios. To some extent, this could mean that parents just do not value quality. But it could also mean that parents also realize that these structural measures are not what matters when it comes to quality, which is in line with what the evidence shows. And that is why they are unwilling to pay higher prices.

But either way, the reason that high-quality childcare does not exist is that parents are unwilling to pay for it, as research has shown, and not necessarily due to market failure.

Conclusion

Certainly, having well-adjusted productive members of society is good for the whole state of Minnesota. But well-adjusted productive members of society are not exclusively a result of access to childcare.

For the average child, access to formal childcare has no additional benefits compared to the care received at home. In fact, for some kids, access to childcare might prove to be even more detrimental to their wellbeing than having no childcare at all.

Childcare providers have low wages because the government, through strict regulation, forces them to subsidize tuition. Similarly, parents cannot find affordable childcare because the government raises prices through strict regulations. These strict regulations, however, do nothing to raise the quality of child care.

Simply put, the childcare crisis is not due to market failure. And, increasing public spending on childcare to cure this market failure would do nothing to lower the cost of high-quality affordable childcare.