The macroeconomics of pandemic and recovery

As the pandemic passes and national and state economies reopen, what is in store for the economy? Some basic macroeconomics might tell us.

Theory

The macroeconomics of a pandemic

When COVID-19 hit early last year, state governments across America declared shutdowns of businesses and ordered people to stay home. We can illustrate the economic effects of this using the sort of supply and demand chart that will be familiar to anyone who has studied any economics.

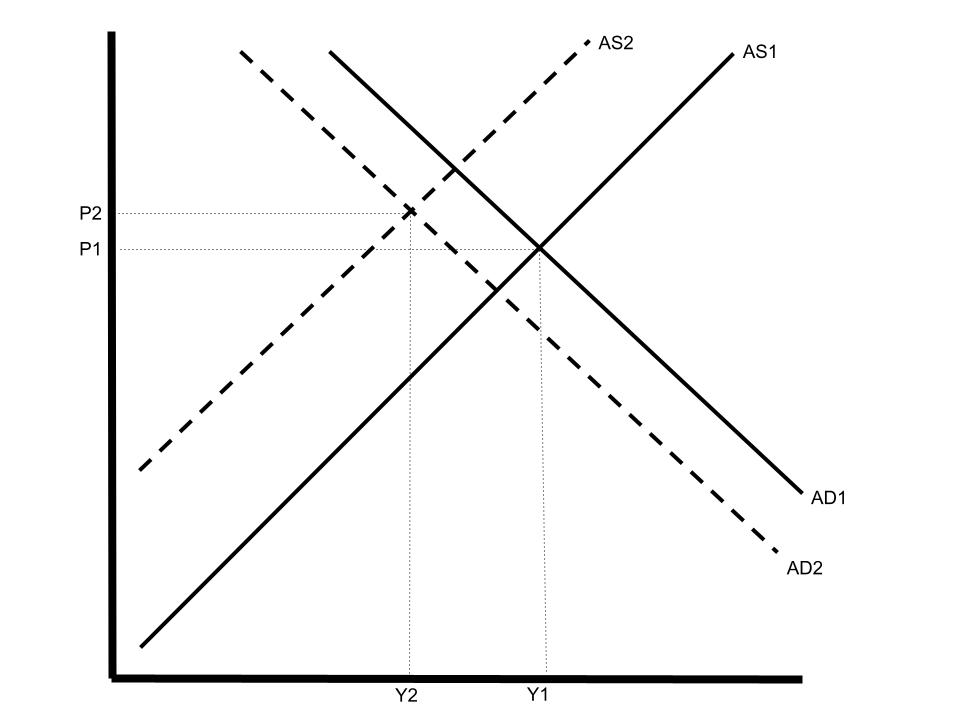

As Figure 1 shows, pre-pandemic, Aggregate Supply in the economy was AS1, Aggregate Demand was AD1, output was Y1, and the price level was P1. When the pandemic hit and governments responded by shutting down businesses, Aggregate Supply fell, shifting to AS2. As people stopped spending, either because they had lost their jobs or because there were fewer opportunities to spend, Aggregate Demand fell to AD2. I’ve assumed the fall in Aggregate Demand was smaller than the fall in Aggregate Supply owing to federal spending on things like stimulus checks and ‘enhanced’ unemployment insurance. The result of all this is a new pandemic equilibrium, where output is lower, at Y2, and the price level is higher, at P2.

Figure 1: The macroeconomics of a pandemic

The macroeconomics of a recovery

What happens when things open back up?

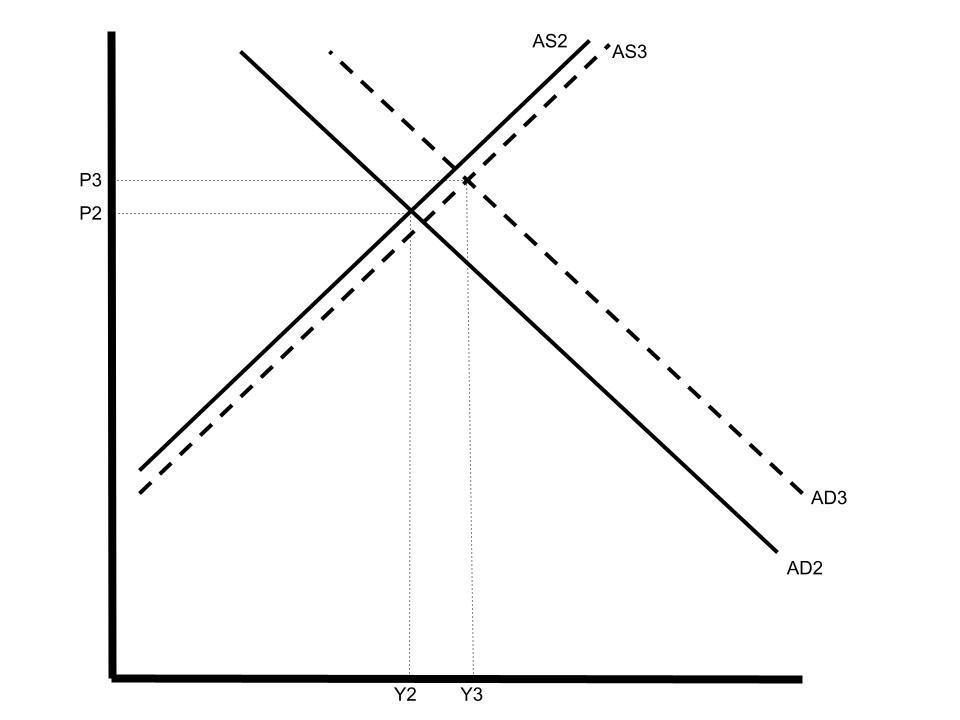

In Figure 2, the Aggregate Supply curve shifts back to the right as businesses reopen. But a business, once closed, doesn’t restart overnight. So, I’ve assumed that, at present, we are not all the way back at AS1 but at AS3, which is lower. Aggregate Demand, by contrast, I’ve assumed to be pretty much back to where it was as pent up demand becomes effective. So, we move from AD2 to AD3. The result is that output rises from Y2 to Y3, but prices also rise from P2 to P3. Simply put, demand is increasing faster than supply so prices are going up – inflation.

Figure 2: The macroeconomics of a recovery

Practice

The lumber industry offers an illustration of this theory in action. CNN reports:

As the pandemic crushed the US economy last spring, sawmills shut down lumber production to brace for a housing slump.

So there is our Aggregate Supply curve shifting left. But:

The slump never arrived and now there isn’t enough lumber to feed the red-hot housing market.

Our Aggregate Demand didn’t move as much (at all, in some cases). And, so, as demand increases relative to supply, we have surging prices:

The shortage is delaying construction of badly needed new homes, complicating renovations of existing ones and causing sticker shock for buyers in what was already a scorching market.

Random-length lumber futures hit a record high of $1,615 on Tuesday, a staggering sevenfold gain from the low in early April 2020.

What happens next?

These high prices might seem to be a problem. They are not. They are the symptom of a problem, namely the changed balance between lumber supply and demand. Fortunately, these prices are also signals: big, flashing signs screaming: “Produce more lumber.”

The good news is that industry executives expect lumber production to catch up with demand — eventually.

Samuel Burman, an assistant commodities economist, predicted in a recent note to clients that there will be a “sharp fall” in lumber prices over the next 18 months.

“The mills are coming back online. I think we’re past the worst of it in terms of supply availability,” said Mezger, the KB Home CEO.

It isn’t just lumber, as Bloomberg reports:

From steel and copper to corn and lumber, commodities started 2021 with a bang, surging to levels not seen for years. The rally threatens to raise the cost of goods from the lunchtime sandwich to gleaming skyscrapers.

A WCCO report shows this making itself felt in household budgets:

The average prices in March of 2021 for pork chops and chicken breasts are both up more than 10% compared to March of 2020. Eggs and cheddar cheese are both up 6%.

Looking at all consumer goods as a whole, the latest inflation data in the Consumer Price Index from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the largest month-to-month increase in almost nine years.

…

It’s a similar story at the gas pump. Prices have jumped more than $1.20 compared to a year ago, but that was when demand was at rock bottom because so many people were at home.

As with the lumber industry, as supply expands in response to these higher prices, we should expect to see inflation slacken. A one-off dump of purchasing power into an economy will lead to a one-off jump in prices. Whether or not this inflation continues, which some worry about, depends on whether this infusion of purchasing power, from government spending and money printing, is sustained. If it is not, inflation could well be expected to drop back. If it doesn’t, we may be worrying about something we haven’t for a while — inflation.

The problems facing the American economy at present are supply side problems. Demand side measures — like more ‘stimulus’ and expanded unemployment insurance — will only make matters worse.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.