Why ‘greed’ isn’t to blame for higher prices

Are people greedier here?

Recently, I had an op-ed in the Star Tribune arguing that the high housing costs we face in Minnesota are not a problem, but rather a symptom of a problem, that problem being an excess of demand for housing relative to supply. This is caused, in large part, by excessive taxes, fees, and regulations, which effectively make it illegal to build affordable housing here.

A journalist friend of mine once told me “Never read the comments.” Having read the comments once or twice, this has proved to be good advice, but I broke the rule for this piece and saw the following reply:

But if greed is the illness causing high house prices in Minnesota, that begs the question: Why are people greedier here than they are in Wisconsin, Iowa, South Dakota, or North Dakota?

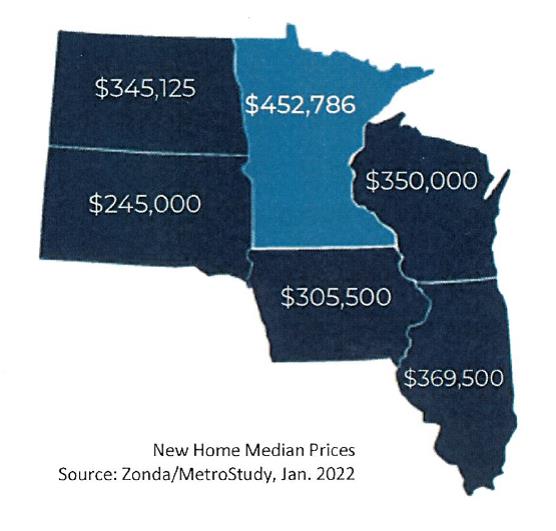

Figure 1 shows that, in January 2022, the median price of a new home in Minnesota was $452,786. This was 29 percent higher than in Wisconsin, 31 percent higher than in North Dakota, 48 percent higher than in Iowa, and a staggering 85 percent higher than in South Dakota.

Figure 1: New median home prices, January 2022

How does greed explain these differences in house prices? Are house builders in Minnesota 31 percent more greedy than those in Wisconsin or 84 percent more greedy than those in South Dakota?

The phenomenon we have to explain is not just why Minnesota’s housing is so expensive, but why it is so much more expensive than in neighboring states. If you believe that “greed” is the reason our housing is so much more expensive, I’ll ask you why you think Minnesota’s builders are so much greedier?

I’ll look forward to an answer.

Are people greedier now?

If you are trying to explain differences between two things, you have to start with variables that are different between those two things. I don’t think it is remotely likely that builders in Minnesota are 84 percent greedier than those in South Dakota, so there must be some other factor or factors at work, including those taxes, fees, and regulations.

What is true in explaining differences between states is also true if you’re trying to explain differences between two points in time. This is why blaming America’s current high rate of inflation on ‘greed’ — as Sen. Elizabeth Warren is wont to do — is so wide of the mark.

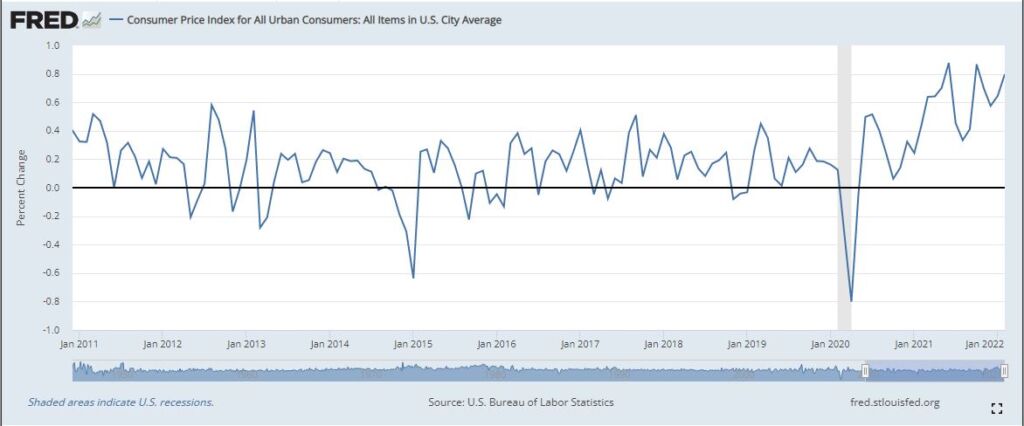

Figure 2 shows the monthly rate of inflation since December 2010. If you think ‘greed’ was the cause of the 0.8 percent rate in February, why do you think businesses were greedier in that February than in February 2011 when the rate was 0.3 percent? Or February 2017, when it was 0.1 percent? Why do you think that businesses which were so un-greedy in April 2020 that the inflation rate was actually a negative 0.8 percent have suddenly become so much greedier?

Figure 2: Monthly change in Consumer Price Index

The answer is that they didn’t. Something else is driving this.

Greed is a constant, look for the differences

Like it or not, greed is more or less a constant in human nature. If it doesn’t change much, it doesn’t make sense to attribute changes in other things to it — and certainly not differences in house prices of neighboring states or inflation rates from April 2020 to February 2022. So why do people embrace such explanations, which don’t, in fact, explain anything?

One reason is that it is easier. Understanding why new homes are so much more expensive in Lake Elmo, MN, than they are in Hudson, WI, requires getting your head around those differing taxes, fees and regulations. Understanding why the deflation of April 2020 became the inflation of February 2022 requires some understanding of monetary and macroeconomics.

But another reason is that it is comforting. When we see prices rise, we like to believe that it is because somebody intended it to happen. This preserves the idea that to make prices fall, all we have to do is stop that person — or persons — responsible for raising them. It’s an easy fix.

The alternative is that nobody intended for prices to rise by 7.9 percent in the year to March, but they did anyway. That is a much less comfortable thought. If these consequences were not intended but unintended, then how do we find the person responsible? And if we could, how do we remedy the action?

Aside from the usual political reasons, these are, I think, why people like Sen. Warren and that Star Tribune commenter embrace explanations that explain nothing.