Why robots support a higher minimum wage

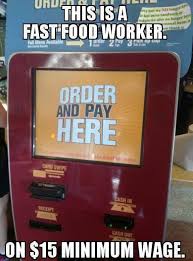

The rather cruel meme below has been going round online for a few years now.

New research shows that this might well be the case.

Bad robots

In a new paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, economists Grace Lordan and David Neumark analyze how changes to the minimum wage from 1980 to 2015 affected low-skill jobs in various sectors of the U.S. economy. They focus particularly on “automatable jobs – jobs in which employers may find it easier to substitute machines for people”, such as packing boxes or operating a sewing machine. Lordan and Neumark find that across all industries they measured, raising the minimum wage by $1 equates to a decline in ‘automatable’ jobs of 0.43%. Certain industries were affected far more than others. In manufacturing, a rise of $1 in minimum wage drove employment in automatable jobs down a full percentage point. They conclude that “groups often ignored in the minimum wage literature are in fact quite vulnerable to employment changes and job loss because of automation following a minimum wage increase”.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Economic theory says that if you raise the price of something people will switch to substitutes. As with Coke and Pepsi, so with labor and machines. And it is lower skilled, lower wage, jobs that are easiest to automate. What matters is the relative price of labor and capital inputs of equal productivity. This can also shift in automation’s favor by a fall in the price of technological substitutes for labor. Given technological progress, this is pretty much always happening.

More capital per worker is a good thing, up to a point. It makes workers more productive and raises their wages. But if that is accomplished simply by freezing some workers out of the labor market with minimum wage increases, then the outcomes will be very different to those the policy’s advocates might expect.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.