Cheer Up, Bonnie. Things Are Getting Better

Bonnie Blodgett recently penned this opinion piece in the Minneapolis Star Tribune. The piece started off as a fairly normal left-of-center piece on the environment, but then it veered off the rails as she began to discuss agriculture.

It’s a weekend and the sun is out, so I’m not going to go into a lot of detail about the piece, but here are a few quick excerpts from her article and my reaction to them:

When we unearth carbon, whether in liquid form (oil) or as vapors (natural gas) or squishy bogs (peat) or rock (coal), and light a match to it, we release (as CO2) what it took Mother Nature millions of years to make. Her intention was that, in effect, plants fertilize plants. If you break that cycle of life, or accelerate it, as we’ve done, it’s not just the weather that changes but also our ability to grow the food we need to survive as a species.

It is true that humans have increased the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but the author was incorrect when she asserted that it was reducing the world’s ability to grow food.

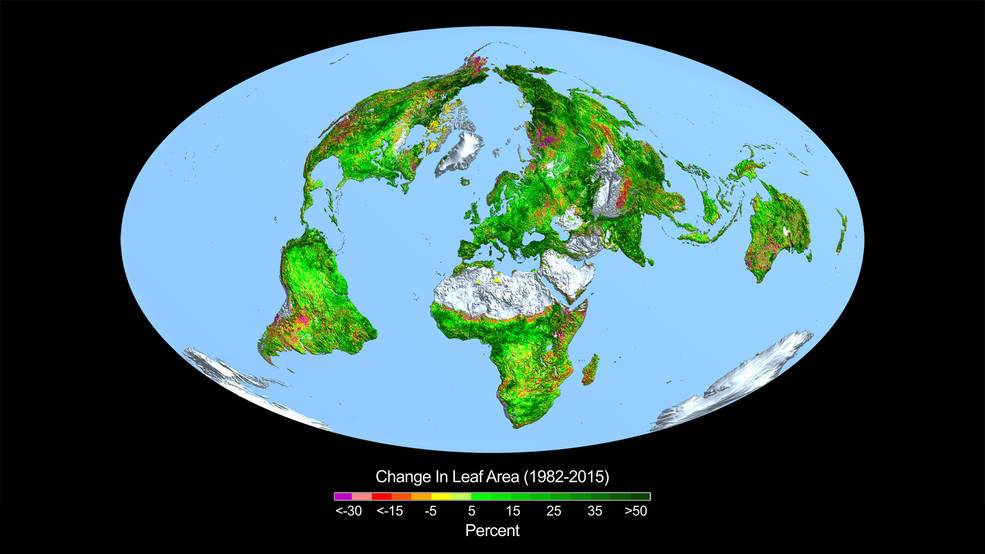

In fact, increasing CO2 concentrations has led to plants growing faster and more robust. But don’t take my word for it, as shown in this diagram from a NASA study.

We all know that plants turn carbon dioxide into oxygen, but few of us realize that more CO2 in the air increases the rate at which plants grow. Greenhouse owners actually pump additional CO2 into their facilities to stimulate plant growth. This is like a football player taking an oxygen mask during a game.

Ironically, by relying more and more on synthetic fertilizers to feed the world, we are making matters worse. Why? Because synthetic nitrogen is made by a process that is fossil-fuel intensive. Without petroleum there would be no chemical runoff into our waters; or huge combines, which run on fossil fuels, because farms would be smaller; or a soy-corn crop rotation; or animals raised in warehouses on a diet of soybeans and corn.

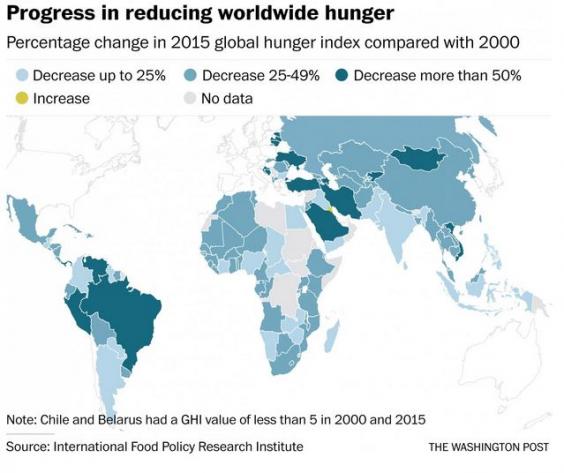

This assertion is demonstrably false. Although too many people are still undernourished, there are fewer people who are going hungry today than there were 20 years ago, according to charts produced by the Washington Post. This is because of synthetic fertilizers, not in spite of them.

I grew up on a dairy farm in Wisconsin, and can tell you that we would not want to live in a world where we did not use oil for farming. Hard data show that you wouldn’t, either.

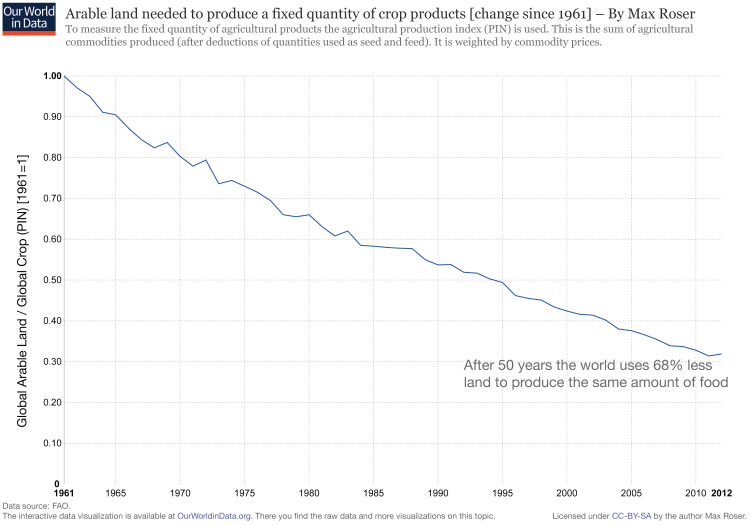

Farming has become more efficient because of technological advances, many of which require fossil fuels like oil and natural gas. We are able to grow more food per acre, which reduces the cost of food for everyone, and it also means we can set aside more land for forests and habitats because we don’t need to clear cut it to keep people from starving.

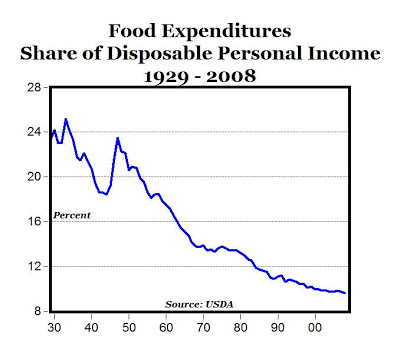

Per-capita expenditures on food in the United States plummeted as gasoline and diesel powered tractors supplanted horses as the primary means of farming. The trend is irrefutable. Controlling for World War II, which affected food prices, the cost of food for Americans has declined steadily thanks to improved farming techniques and technology.

Improved efficiency also means we do not need to plant as many acres to grow the same amount of food. This is a very good thing. It means the world can better meet the nutrition needs of the global population while at the same time having more land to set aside for conservation.

Imagine this: The United States abandons modern farming techniques and goes back to a “more natural” form of farming. This causes scarcity in food markets, which causes prices to rise. Suddenly, soybeans are more expensive and folks in Brazil clear more rain forest to grow crops.

That’s how it works, folks.

When soil can’t absorb all the rain that falls in a torrent, the excess water runs off into lakes and streams, taking both organic matter and synthetic chemicals with it. These in turn feed the soil in the wrong places — places like streambeds. Lake Pepin is literally filling itself in. Weeds thrive in this phosphate- and nitrogen-rich (and oxygen-poor) habitat, but other species don’t. Meanwhile, the Gulf of Mexico, where all these chemicals end up, is experiencing a similar problem. The so-called Dead Zone is now the size of the state of New Jersey.

I will be the first to admit I don’t currently know much about the so-called Dead Zone, but I left that paragraph in this post to avoid accusations of cherry-picking paragraphs.

I am a gardener. Gardening fanatics are by definition stewards, just as farmers are. Horticulturists and agriculturists used to belong to the same “tribe.” As industrial processes transformed farming from a natural to an industrial process, the two disciplines diverged because gardeners don’t grow plants for a living but for love. Thus, we are not dependent on a system but have the tremendous luxury of doing as we like in our own backyards.

People used to have gardens because they needed them to feed their families. My grandma, a survivor the the Dust Bowl in South Dakota, always put in a large garden because she enjoyed it, but also because she came from a generation where it was an indispensable part making a living.

Modern agriculture is the reason why the author has the luxury of growing plants because she loves to do it, and not to make a living. That’s why her earlier criticisms of our farming methods seemed so curious.

Here’s a suggestion: Instead of gazing out the window in despair because winter seems to have gotten itself stuck, spend those idle hours starting seed under lights.

I couldn’t resist this last comment. In Minnesota, her lights are probably being kept on by coal, natural gas, or nuclear power, which make up the vast majority of electricity generation in the state.

Cheer up, Bonnie! You’ll be planting outside soon. Until then, enjoy planting your seedlings under coal-fired lights.