Recycling Markets Have Changed. Will Minnesota Cities Adapt?

One of the core arguments for limited government involvement in the private sector is that private companies are much more receptive to changes in market conditions than governments because they are sensitive to price. If the price of a product plummets, the private sector produces less of that product, but this is not how governments operate because politicians aren’t sensitive to dollars, they’re sensitive to votes.

When it comes to issues like recycling, emotions often trump economics, which is why local elected officials around the country often campaign on higher recycling rates, even though these decisions never made economic sense. Now, the Star Tribune reports, recycling programs in some Minnesota cities have become a net cost because China is no longer accepting recyclable materials. Unfortunately, this means cities will likely see recycling programs eat into their budgets unless local politicians are willing to critically evaluate whether their recycling programs still make sense and consider alternatives if they don’t.

Burning a Hole in City Budgets

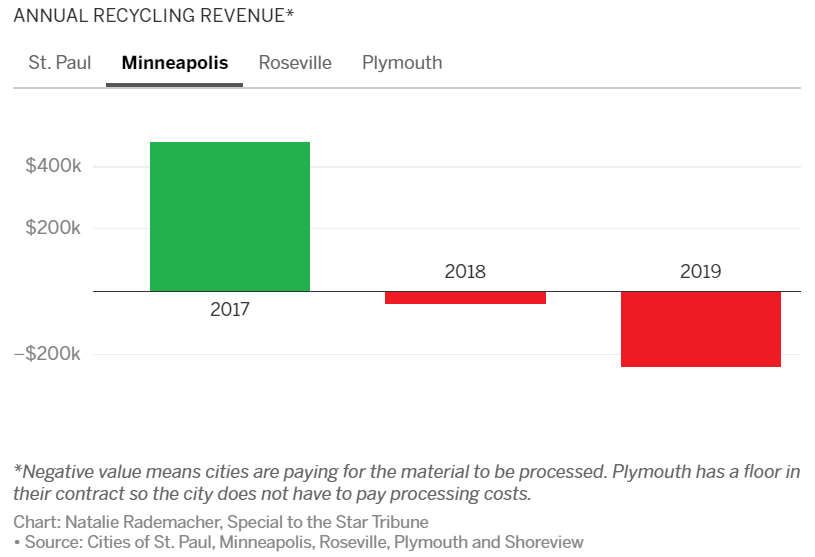

According to the Star Tribune article, the City of St. Paul lost more than $325,000 on recycling programs last year, Minneapolis lost $240,000, Roseville lost $75,000, and Plymoth lost nothing, because they negotiated a price floor into their contracts. I’ve modified the figure that appeared in the Star Tribune article for Minneapolis below.

Thankfully, it appears the City is still in the black over a three year period, but considering property taxes keep rising and spending proposals seem to gain zero’s every year, the profits that were accrued from the recycling program in prior years have likely already been spent. With an enormous drop in demand for all materials this year due to the likely COVID-19 global recession, the City is likely to lose much more in 2020 than it did in 2019.

In St. Paul, the bleeding will likely be worse, and City residents will likely have to foot the bill for higher recycling costs in the future, according to the Strib:

“Last year, St. Paul paid more than $300,000. While the city has a recycling fund to help with these new costs, residential rates will likely increase when the city negotiates its next contract with Eureka.

“Our piggy bank is drying up,” said Susan Young, St. Paul city manager of resident and employee services.”

Given these complications, local officials should take a hard look at their finances to see if their recycling programs make sense.

Does Recycling Make Sense?

The short answer is sometimes, but mostly not. The problem with recycling is that nobody really has an incentive to do it correctly or a disincentive for doing it incorrectly. This lack of good incentives means people do it wrong all the time. According to the Star Tribune article:

“Another problem that brings down the value of recyclables is that non-recyclable items often end up in the blue bin. This contamination makes it harder for haulers to sell the material. In a crowded recycling market, companies can be more picky about what glass, cardboard and other recyclables they purchase.

Gone are the days when consumers were encouraged to recycle as much as possible, which often led to “wishcycling.”

Recycling is an emotional good, where people like it because it makes them feel like they’re good people, not an economic good. Despite how people feel about recycling, the facts say that the costs outweigh the benefits for the vast majority of materials. This is why many items placed in recycling containers, many of which aren’t really “recyclable,” are ending up in landfills and garbage burners.

Those who argue that recycling is better for the internment should think about whether it makes sense to send a separate fleet of trucks out to collect materials if a large percentage ends up where the rest of the garbage goes.

All this being said, some products do make sense to recycle, as American Institute for Economic Research, Professor Michael Munger explains:

“Recycling requires substantial infrastructure for pickup, transportation, sorting, cleaning, and processing. … For recycling to be a socially commendable activity, it has to pass one of two tests: the profit test, or the net environmental-savings test.”

If something passes the profit test, it’s likely already being done. People are already recycling gold or other commodities from the waste stream, if the costs of doing so are less than the amount for which the resource can be sold.”

Valuable materials will be recycled under free-market conditions because the cost of recovering them is less than the profit that can be made by doing so, but recycling becomes an economic loser when cities or states mandate the use of these programs, effectively institutionalizing them and creating entities that are divorced from price signals or market realities.

Conclusion

Cities and states are going to have massive budget shortfalls as a result of the COVID-19 recession, and this will force them to make very tough choices about their budgets. Many cities in the state have already reconsidered their recycling programs and have reduced the number of pickups, or even stopped collecting it entirely. These options will have to be considered if cities continue to bleed cash as a result of these programs. At the very least, all cities in Minnesota should follow the Plymouth model, which places price floors on recyclables moving forward to protect taxpayers and residents from fluctuating prices for recyclable materials.