Electric Vehicles Are “Trickle Down” Environmentalism

Electric vehicle (EV) supporters often argue that we need to subsidize and mandate EVs to help improve air quality and the environment in low-income and minority neighborhoods in Minnesota. But how can EVs improve air quality for these communities when it is almost always wealthier, white people who live in affluent neighborhoods who buy EVs?

For all the criticism liberals usually lobby at supply-side economics, they seem to love the idea of trickle down environmentalism, where wealthy urbanites can act as if they’re saving the world and delivering environmental justice to the downtrodden by forcing these same communities to subsidize their new electric car.

EV Rebates and Subsidies: A Wealth Transfer From the Bottom To the Top

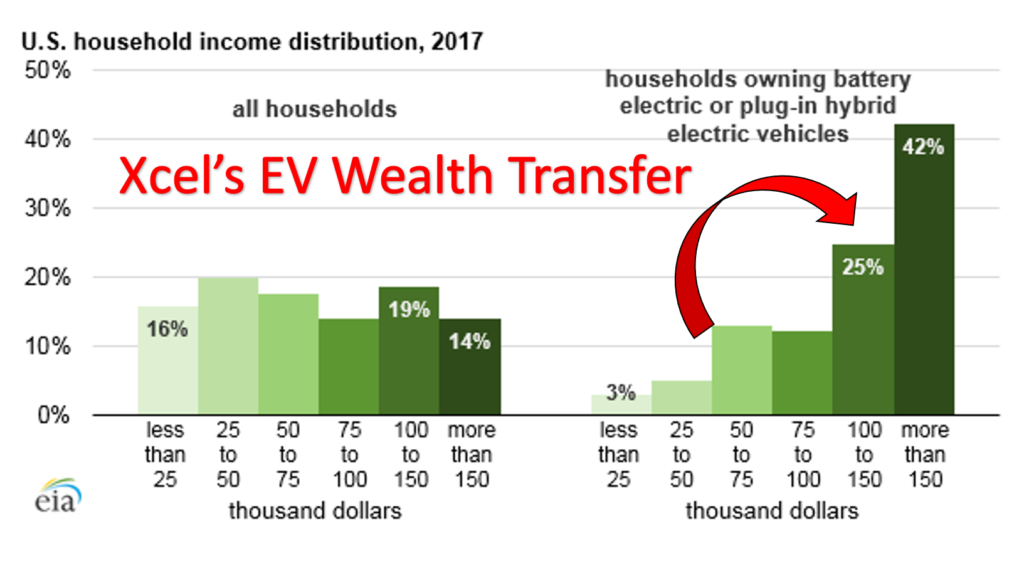

Subsidies for electric vehicles are the definition of regressive. According to data from the Energy Information Administration, 67 percent of households who owned electric vehicles made more than $100,000 in 2017. This means the $7,500 federal tax credit, the DFL proposal to give a $2,500 rebate to Minnesota EV buyers, and Xcel Energy’s proposed $2,500 rebates could put as much as $12,500 in rebates and tax credits into the hands of people who are already wealthy.

All of these “freebies” would be paid for through tax increases and rising electricity bills for lower-earning households to fund a luxury item for more-affluent ones. How is that “environmental justice?”

California Car Mandates: Driving Up Costs

Mandates for electric vehicles are also problematic because the California car mandates proposed by Governor Walz are estimated to increase the cost of gasoline-powered cars by up to $2,500 per vehicle.

Increasing the cost of new vehicle ownership makes it more difficult for low-income families to afford a dependable car, and it also likely to make it more difficult to find quality used cars, as a higher price point could result in vehicle owners holding on to their cars longer. This could ultimately end in a situation where older cars, which emit more from the tailpipe, are repaired and driven longer than they would be otherwise if newer used models were more available.

Swapping out older, more-polluting models for newer, less-polluting models would improve local air quality, but putting up barriers to this fleet turnover impedes the goal of improving local air quality.

How Electric Vehicles Will, or Won’t, Improve Local Air Quality

Minnesota’s air monitoring data show that the state meets all of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

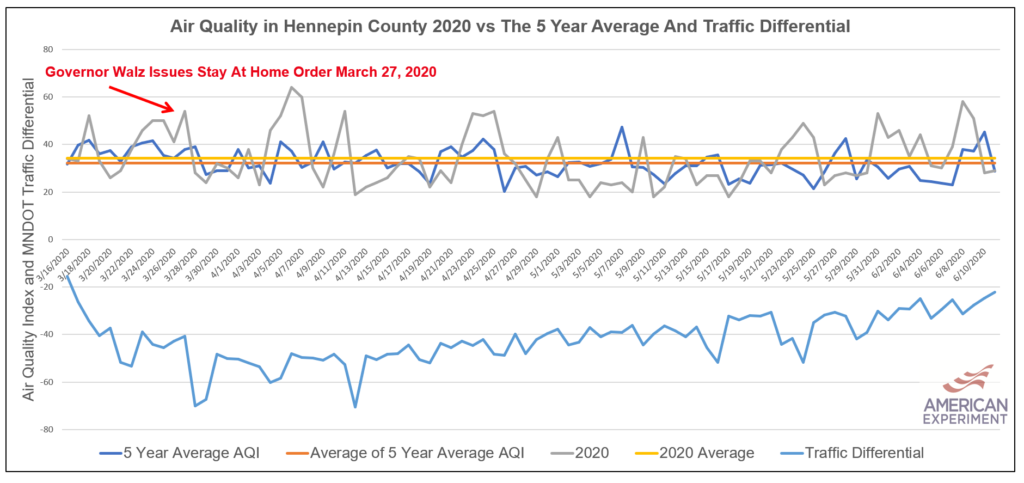

In fact, Environmental Protection Agency air monitoring data show that air pollution levels were higher in 2020 during the Governor’s first COVID shutdown than the previous five-year average. Higher levels of pollution were observed in 2020 even though traffic was down 40 percent, according to data from MNDOT.

This data feels counterintuitive, but this is why data is so vitally important to the scientific method. The fact that air monitoring stations throughout the Twin Cities detected more levels of pollution this year, when there was far less traffic, show that our air is already incredibly clean and that larger factors out of our control, such as regional weather systems, have a bigger influence on air quality than what kind of cars we drive.

Nonetheless, EV advocates often claim that the EPA air monitors can detect regional trends, but they argue EV’s can help air quality in local neighborhoods. They don’t have much evidence for this claim, but we can explore whether EVs would help make a difference on this front, anyway.

In order for EVs to make much difference in these areas, people in low-income neighborhoods would need to drive them, but this isn’t likely to occur because EVs are more expensive and less useful than gas powered vehicles.

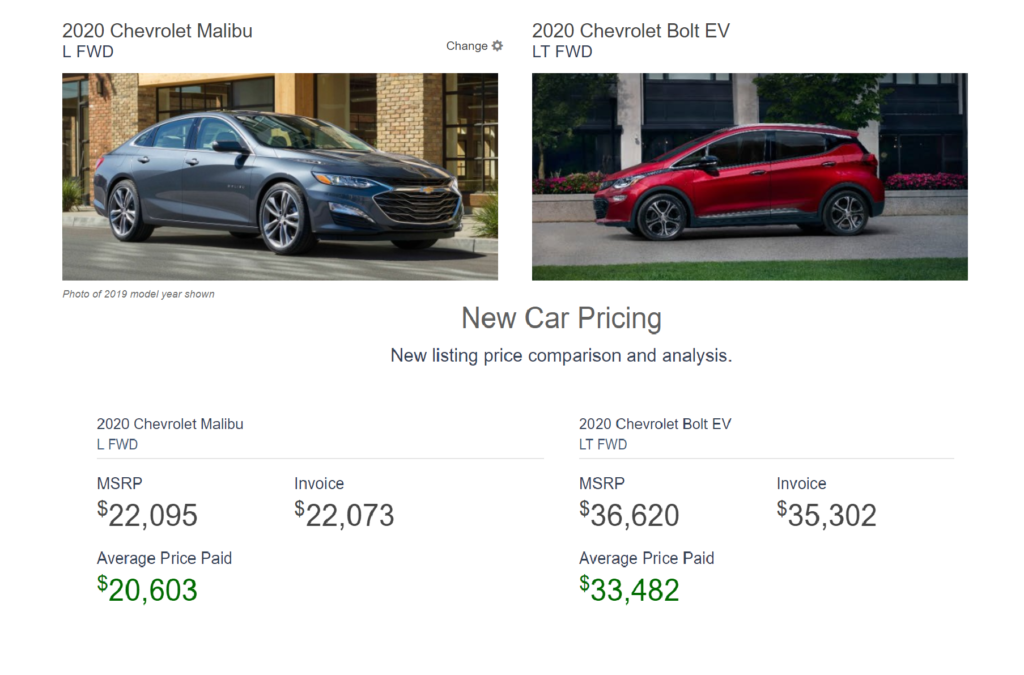

For example, a Chevy Bolt EV is about $13,000 more than a gas-powered Chevy Malibu. Because tax credits are a subsidy eliminating tax liability, a low-income family would be unlikely to be able to use the $7,500 credit because they probably don’t have $7,500 in tax liabilities to offset. This means the Malibu is by far the lower cost vehicle for this family.

Not only do EVs have higher upfront costs, but they are also less useful than a gas powered vehicle. EVs have shorter ranges, require a long time to charge on home chargers, (it takes up to 20 hours to fully charge a car on a standard 120 volt outlet and it takes 3 hours on a 240v outlet), and they also lose about 40 percent of their range when the thermometer dips below 20 degrees F. This is why many EV owners also have a gas powered vehicle.

If you are living in a single-car household, it doesn’t make sense to pay more for a vehicle that is less useful. As a result, there will be fewer EVs in low-income neighborhoods, which means they won’t be able to improve air quality there. In fact, the rising electricity costs from Xcel’s proposed EV rebate mean these families will have even fewer resources at their disposal to buy a newer used car that would emit less from the tailpipe.

Conclusion

Siphoning money from low-income households to pay for EV subsidies for the wealthy is trickle down environmentalism that leaves low-income communities fewer resources to purchase newer used cars that pollute less. The benefits, both environmental and financial, overwhelmingly accrue to the latte sipping wealthy folks who buy EVs, while everyone else is worse off. Those who advocate for “environmental justice” won’t find it by promoting more subsidies and mandates for EVs.