Covid-19 shutdowns are crippling Minnesota’s labor market

In December, Congress passed a $900 billion COVID relief package. Of the measures was the extension of federal unemployment insurance benefits by 11 weeks, affecting about 120,000 Minnesotans. A consequence of this, MinnPost reported, was that:

…the bill will negate the need for Minnesota to provide those benefits and cancel a plan to borrow up to $200 million from the federal treasury (thought the state plan was to add 13 weeks, not 11). That borrowing might have forced a future repayment by the state and the employers who pay into the state’s unemployment trust fund. The unemployment insurance provisions in the new bill will also add $300 per week on top of current state benefits through March 14.

If the government is preventing people from earning a living by opening and closing bits of the economy, but this measure is not without its downsides. Last week, Fox 9 reported:

On Wednesday afternoon Governor Tim Walz is expected to announce changes to indoor dining and restrictions at Minnesota restaurants. That means restaurant owners are working to order food and alcohol to serve to customers while trying to bring back staff they had to lay off during the shutdown.

“When you have to let off most of your team, which is, for a lot of us, our family, we have to chase them back up and a lot of them, unfortunately, have already found new jobs,” manager at Broadway Pizza in Brooklyn Park, Brad Oleary said.

…

Oleary says he’s been operating with a skeleton crew during the latest shutdown, with only a few people helping with takeout orders, deliveries and serving the dozen or so people they can have on their enclosed patio. He says, getting employees to come back for another uncertain period of time is a challenge, especially if they are making enough money on unemployment.

“If they’re going to give some checks, help out the people, it might be a little more difficult to get people back to work, but so far it’s been pretty good this time,” Oleary said.

If unemployment insurance offers people an income comparable to working, many of them will opt not to work. This is especially true if that work could be taken at any moment by government edict:

[Bartender Ana Apostolou said] there’s been a lot of uncertainty around her job since the first shutdown in March.

“Not knowing what’s going to happen, if I’m going to have a job tomorrow, if I’m going to come in here and the store be completely shut,” Apostolou said.

Employment uncertainty could be one reason why restaurant owners and managers like Oleary are having a difficult time reobtaining staff after shutdowns.

“How can you expect them to feel any sense of certainty about their livelihood? They’ve been really yanked around a lot here with on and off again employment and that is not for anyone a good way to live your life,” President and CEO of Hospitality Minnesota, Liz Rammer said.

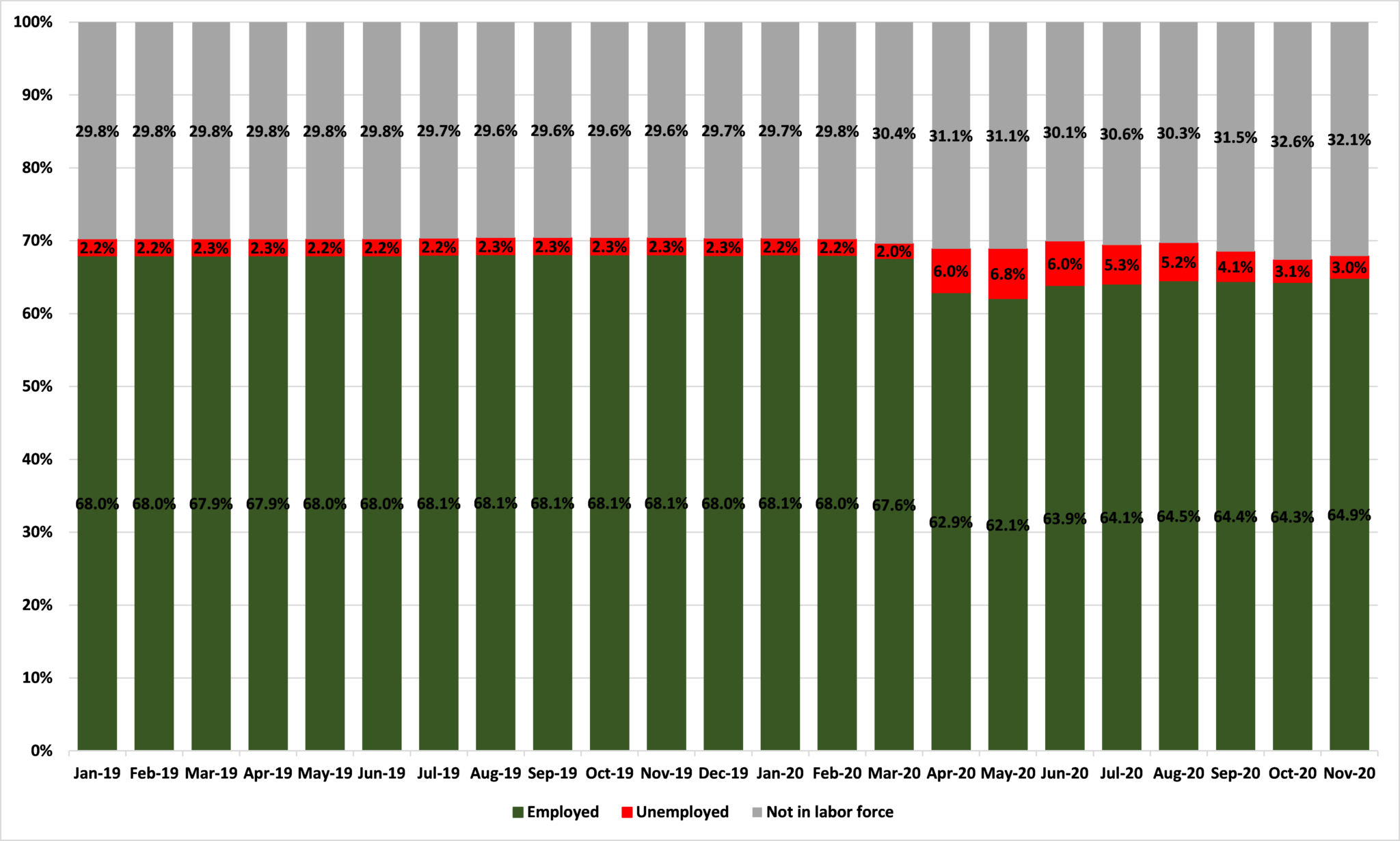

As I’ve written before, the civilian non-institutional population splits three ways in employment statistics: employed, unemployed and not in the labor force. Figure 1 shows how these shares have changed in Minnesota since January 2019. We see the surge in unemployment — those Minnesotans out of work but looking for jobs — in April and May and the gradual decline of that share to 3.0% in November.* But the share of Minnesotans either employed or unemployed but looking, those not in the labor force, is also up. Indeed, it peaked in October at 32.6%. As a result, the Labor Force Participation rate in November, 67.9%, while higher than in October, was still below any months since July 1978.

Figure 1: The employment status of Minnesota’s civilian non-institutional population

Source: Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development

Economists sometimes talk about something called ‘the natural rate of unemployment‘ which is “the rate of unemployment arising from all sources except fluctuations in aggregate demand.” These sources would include government COVID-19 shutdowns. As long as they continue, we can expect the NAIRU to be elevated. This problem will be compounded if unemployment payments are maintained indefinitely at similarly elevated levels.

*The share of Minnesotans unemployed here — 3.0% in November — is different from the unemployment rate — 4.4% in November — because the unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of people unemployed by the number of people in the labor force, whereas here the number of people unemployed is divided by the civilian non-institutional population.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.