How federal regulations—and regulators—held up coronavirus testing

Last week, I wrote about how to deal with the public health crisis which the coronavirus represents. Governments were getting rid of regulations which were apparently supposed to protect public health. I also wrote about the cost imposed by the Food and Drug Administration, in terms of lives and suffering, caused by its delays in approving new treatments.

Often when you criticize regulations, people ask you to be specific, as though you are conjuring up a bogeyman. Well, ok. An excellent article by Alec Stapp for the The Dispatch gives three examples of how regulations and regulators delayed coronavirus testing.

Stapp notes that: “The first coronavirus case in the U.S. and South Korea was detected on January 21”, but that:

Since then, South Korea has effectively contained the coronavirus without shutting down its economy or quarantining tens of millions of people. Instead, the Korean government has pursued a “trace, test, and treat” strategy that identifies and isolates those infected with the coronavirus while allowing healthy people to go about their normal lives.

By contrast:

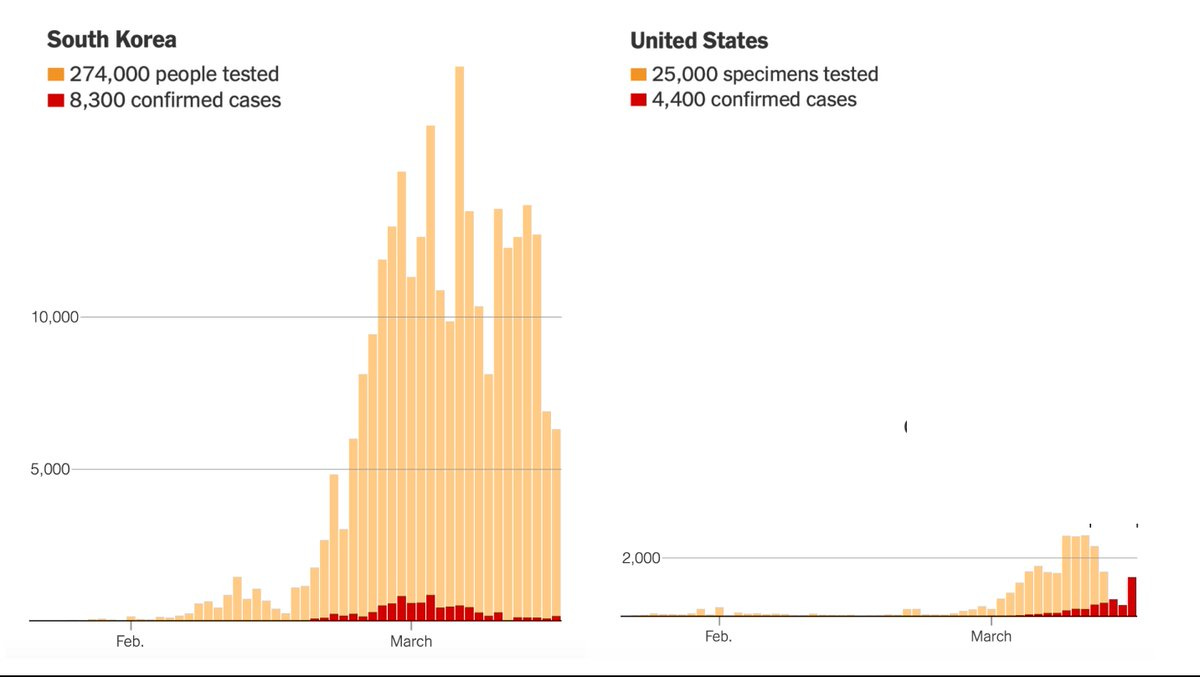

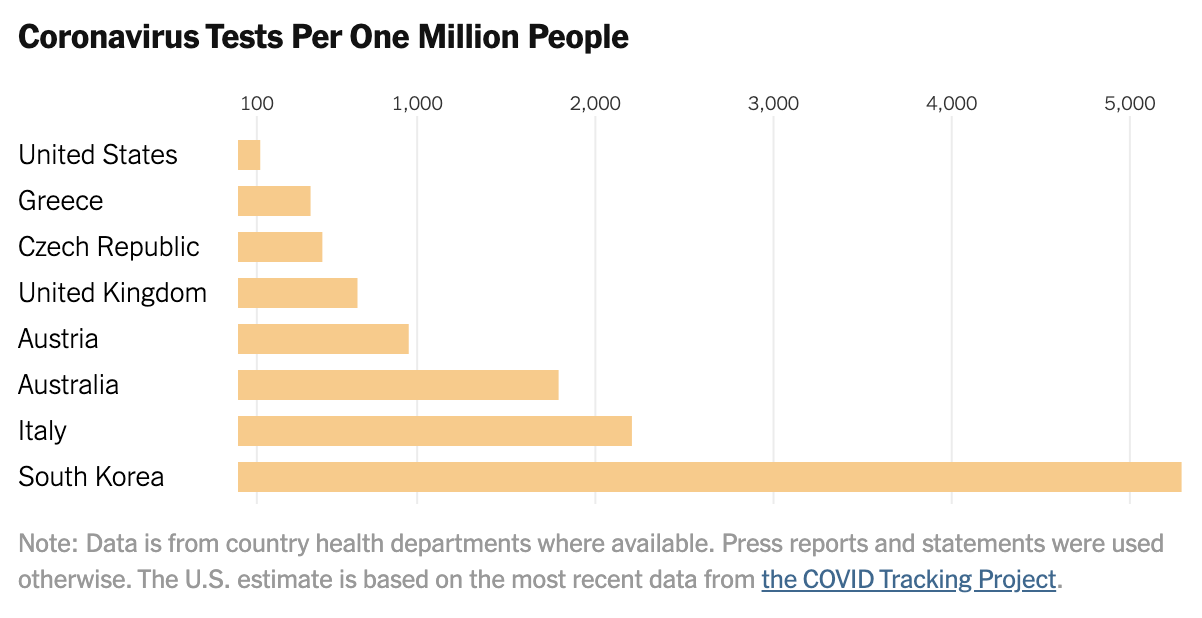

…the United States has not made testing widely available and now various regions are being forced to impose severe economic and social lockdowns. As of March 17, the U.S. had tested only about 125 people per million. South Korea had tested more than 5,000 people per million. Between early February and mid-March, the U.S. lost six crucial weeks because regulators stuck to rigid regulations instead of adapting as new information came in. While these rules might have made sense in normal times, they proved disastrous in a pandemic. [Emphasis added]

He explains:

There have been three major regulatory barriers so far to scaling up testing by public labs and private companies: 1) obtaining an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA); 2) being certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA); and 3) complying with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule and the Common Rule related to the protection of human research subjects.

Laying out a detailed timeline of these failures, Stapp concludes:

The lessons from this debacle are clear: The FDA needs to have plans in place prior to a pandemic for public labs and private companies to produce their own test kits. A distributed strategy would be much more resilient to errors, in contrast to the single point of failure created by the FDA in this crisis. Poor planning and mindless adherence to peacetime regulations led to this abysmal result:

Source: NYT

Source: NYT

Once again we see that regulations ostensibly intended to safeguard public health turn out, when a genuine public health crisis hits, to be positively harmful to public health. When the coronavirus crisis has passed and we are examining it for policy lessons, we ought to begin by not taking regulations or regulators on their own terms.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.