Here’s how stringent regulations raise the cost of daycare in Minnesota

Access to childcare is fundamental to a well-working economy. Unfortunately for Minnesota, childcare is out of reach because it is too expensive or nowhere to be found. Parents in Minnesota pay thousands more for childcare — specifically center-based care — compared to those in other states.

Who is to blame for this? In short, the Minnesota state government. As American Experiment’s newly released report shows, excessive regulations that the state government imposes on childcare providers raise costs which are then passed on to parents.

Certainly, we want childcare centers to be safe and of high quality. But rules meant to regulate safety and quality come with costs that we can’t ignore. For states like Minnesota where the rules are even more stringent, these costs are multiplied manyfold.

This is something that our report illustrates by looking at how rules guiding staff-child ratios, group size limits as well as hiring requirements for teachers affect prices among the states.

Staff-child ratios and group size limits

At a daycare center, children are usually divided into groups. The person in charge of giving primary care to each group of children and designing day-to-day programs is considered a lead caregiver. In Minnesota, childcare workers with teacher qualifications are the designated lead caregiver.

The number of caregivers required per group of children is dependent on staff-child ratio requirements. For Minnesota, the maximum number of infants — aged 6 weeks to 16 months — that can be in one group is 8. And for every 4 infants, centers must have 1 caregiver. This means that centers must have 2 caregivers per group of infants.

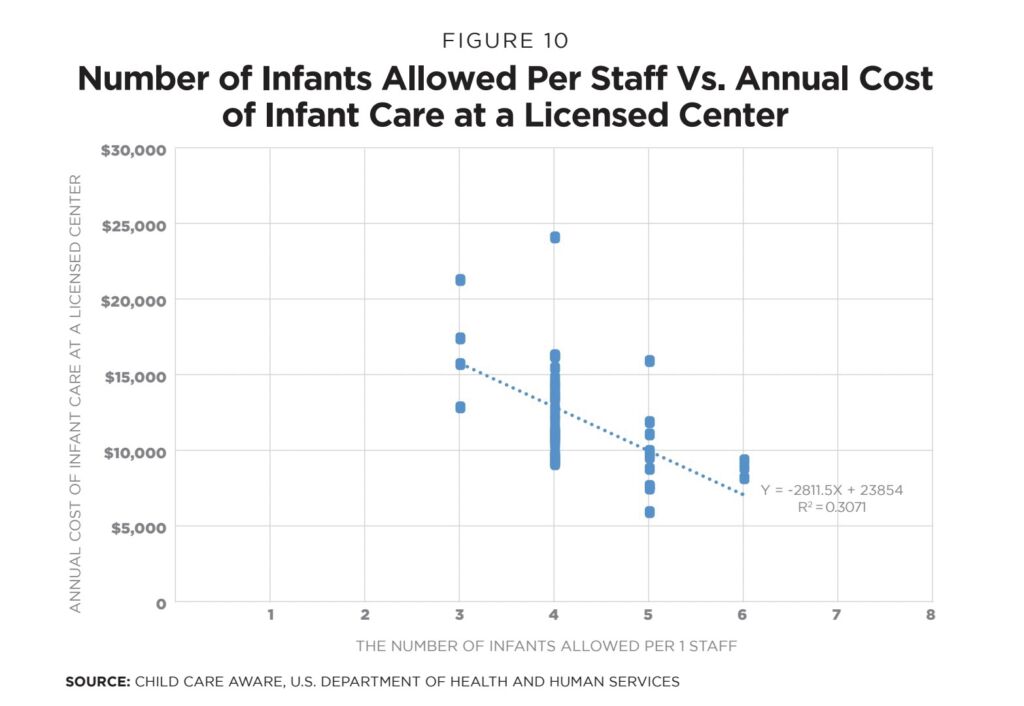

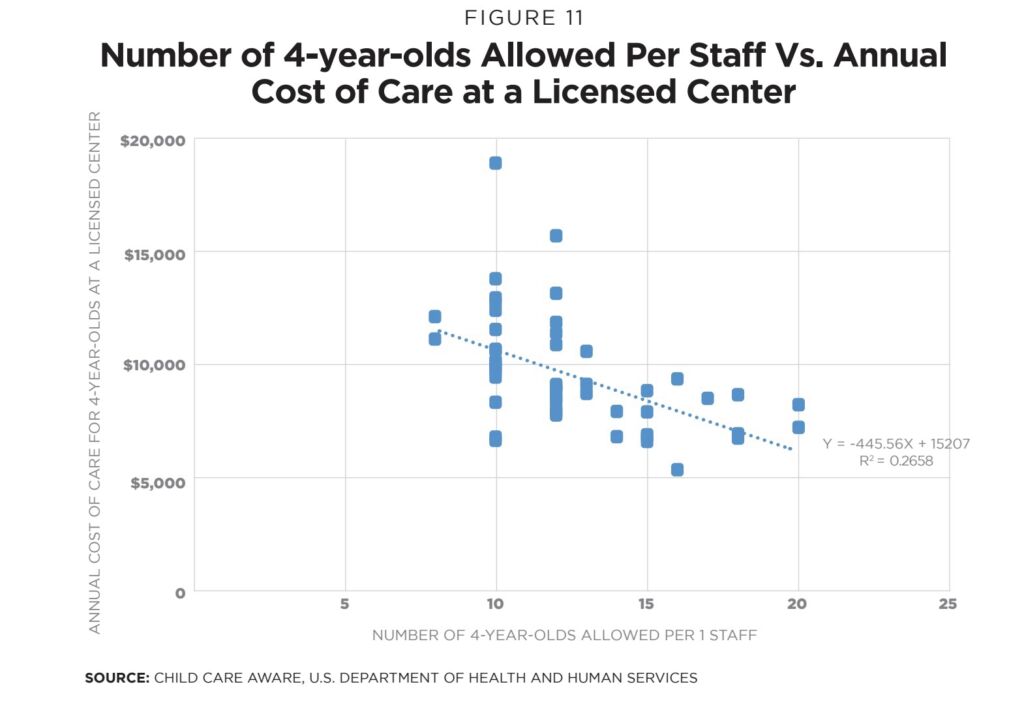

In other states, the rules are different. While Minnesota requires four infants per caregiver and a maximum group size of eight children, places like Colorado, Arkansas, and Mississippi allow a higher number of infants per staff person and more infants per group. Similarly, while Minnesota requires ten 4-year-olds per staff person, other states allow a higher number of children.

This means that in Minnesota, it takes more staff to take care of the same number of children than in states like Arkansas or Mississippi. This in turn means that providers must spend more money taking care of children in Minnesota than in these other states, which raises costs.

Evidence from our report shows that if Minnesota was to allow centers to place five infants per staff instead of four, daycare centers would, on average, be $2800 less expensive.

Similarly, if the state were to loosen laws and allow eleven 4-year-olds per staff instead of ten, the annual cost of daycare for that age group would go down by $450. These results hold even after controlling for income differences among states.

Education hiring requirements

Another significant rule that daycare centers must adhere to is staff hiring qualifications. States have certain limits and standards that dictate what qualifications center workers must possess before they start working.

In Minnesota, for example, to be a teacher at a daycare center, someone with a high school diploma must have 4,160 hours of experience as an assistant teacher and 24 quarter credits from an accredited post-secondary institution. And to be an assistant teacher, someone with a high school diploma must have 2,080 hours of experience as an aide or student intern and 12 quarter credits from an accredited post-secondary institution.

Much like staff-child ratios, these rules are also different in other states. For some states, childcare teachers — or lead caregivers are only required to be 18 and take training before looking after children.

But since center teachers in Minnesota face more stringent regulations, they spend more time and money on education. This means that they often require high wages. And when providers have to pay them more, this raises the cost of daycare.

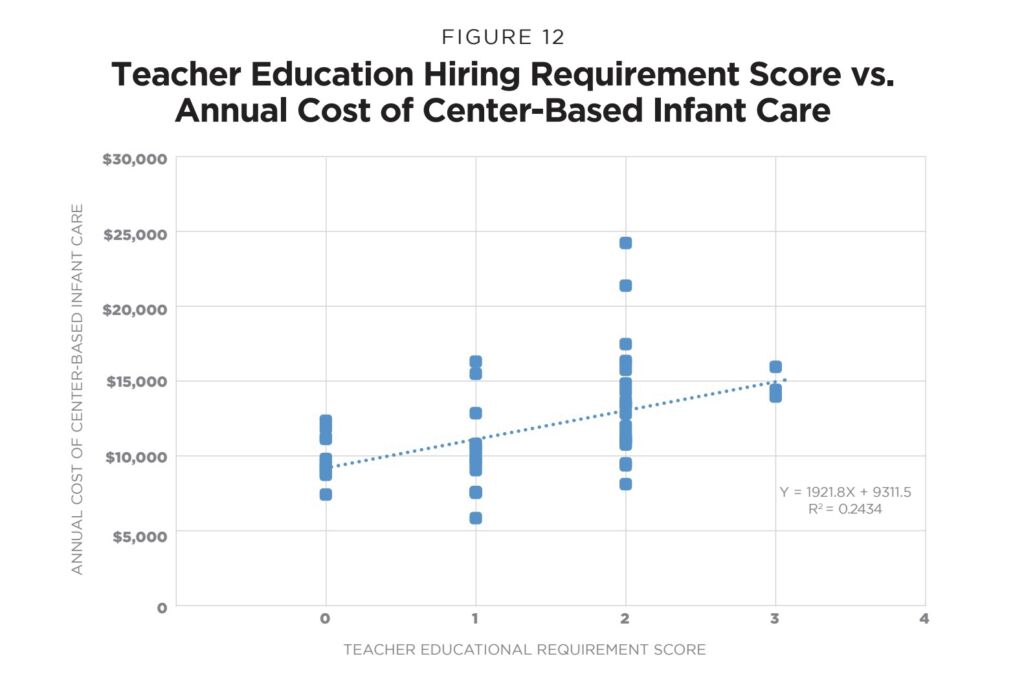

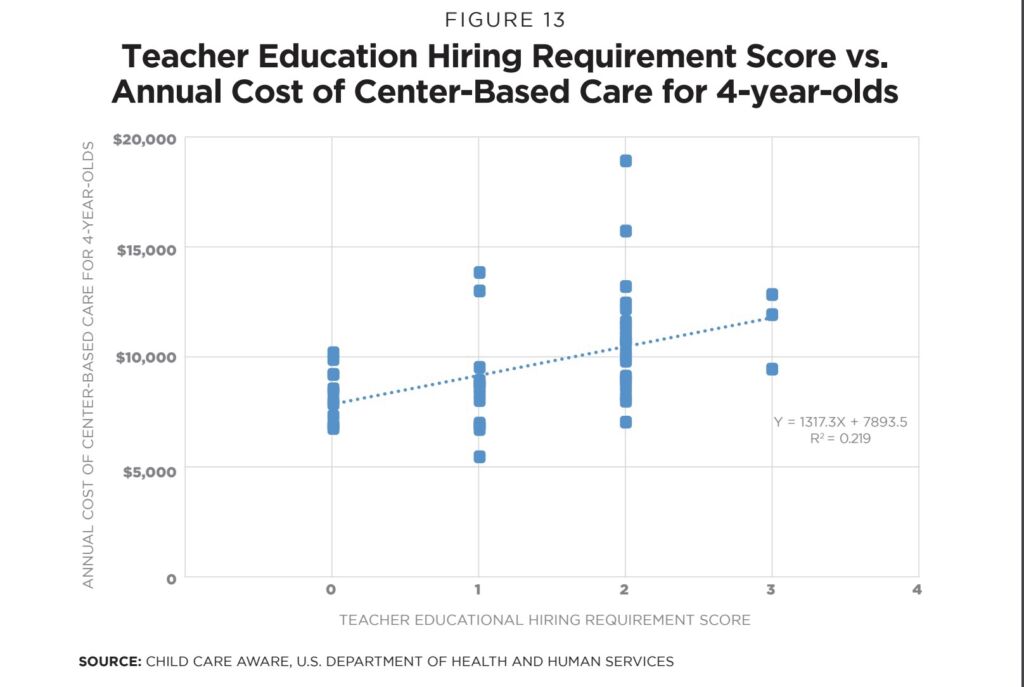

How hiring requirements raise costs

To analyze how teacher hiring requirements raise the cost of care, our study constructed a 4-tiered index score to represent differences in educational hiring requirements for teachers. What this index does is give a score to each state depending on the stringency of their hiring requirements. The higher the score, the more stringent the hiring qualifications.

To be specific, states which do not require a high school education for teachers get a score of 0; states which require high school education but no other additional education get a score of 1; states which require a high school and some post-secondary credits but no bachelor’s degree get a score of 2, and states which require a bachelor’s degree or any other higher qualification get a score of 3.

A regression analysis shows that requiring teachers to have a high school diploma — which is represented by a score of 1 — raises the annual cost of daycare centers by $1,900 for infants. This means that for Minnesota — which has a score of 2 — daycare centers would be $3,800 less expensive for infants if the state were to scrap the high school degree and college credits requirements.

Similarly, requiring a high school diploma for daycare teachers raise the annual cost of care for 4-year-olds by $1,300. For Minnesota, it means care would be $2,600 less expensive for 4-year-olds if the state were to scrape the high school diploma and college credits requirement.

Conclusion

Lawmakers like to think that the cost of living, as well as the nature of the childcare industry, is highly to blame for high prices. And to that effect, they usually propose spending more money on early childhood.

The fact of the matter is that factors like the cost of living have little to do with the high cost of childcare in Minnesota. American Experiment’s new findings agree with previous research; excessive regulation is to blame for the childcare crisis in Minnesota.