If Minnesota is running out of ICU beds, Gov. Walz has failed in his central aim in the fight against Covid-19

Sunday’s Star Tribune carried a dramatic front page story titled: ‘‘No beds anywhere’: Minnesota hospitals strained to limit by COVID-19′. It reported:

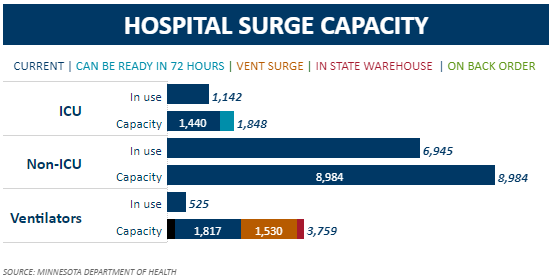

Statewide, 79% of available ICU beds are filled, and 26% filled with COVID-19 patients.

Data from Minnesota’s Department of Health, shown in Figure 1, shows that, at present, 1,142 of the state’s ICU beds are in use. This is 79% of currently available beds, as the Star Tribune reports, and 62% of the total number of ICU beds – 1,848 – available in Minnesota at 72 hours notice.

Figure 1:

There are two things to note about this.

Non-Covid-19 ICU admissions are down sharply – Why?

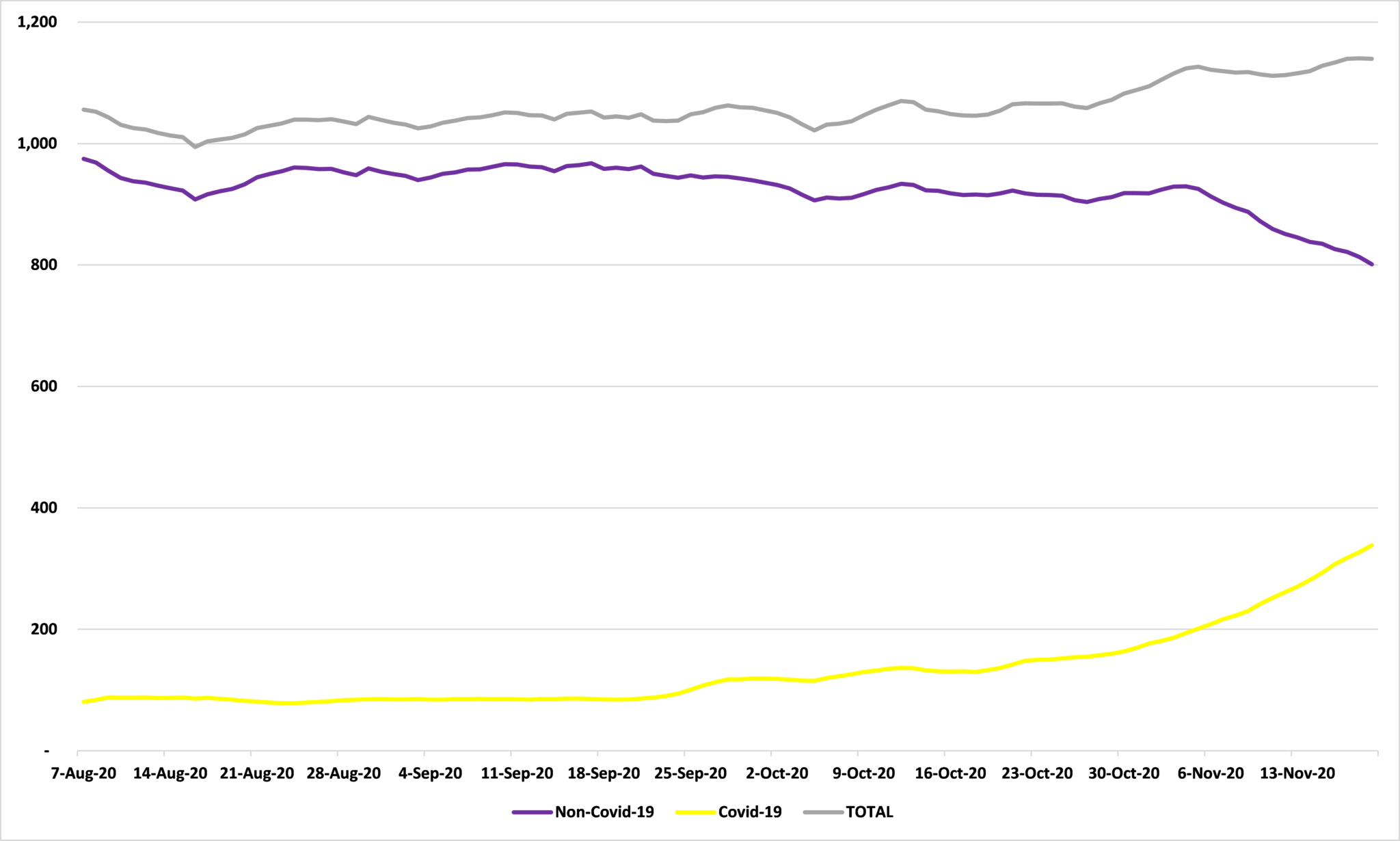

First, as I wrote on Friday, the recent surge in ICU hospitalizations with Covid-19 has been largely offset by a fall in non-Covid-19 ICU hospitalizations. As Figure 2 shows, non-Covid-19 ICU hospitalizations have fallen from a daily average of 930 for the seven days up to and including November 4th to a daily average of 801 for the seven days up to and including November 19th, a fall of 14% in two weeks. As a result, despite the surge in Covid-19 ICU hospitalizations – up 118% from the the seven days up to and including October 27th to the the seven days up to and including November 19th – the total number of ICU hospitalizations in Minnesota has ‘only’ risen by 8% over the same period.

Figure 2: ICU hospitalizations, seven day moving average

Source: Department of Health

On the face of it, this seems strange. Why should non-Covid-19 hospitalizations be taking such a sharp fall? We are heading into flu season which typically sees hospital admissions rise, putting great pressure on hospital capacity even in years without Covid-19 to contend with. Why is this year so different? My guess is that many of these Covid-19 ICU hospitalizations are ones which would have occurred anyway given the usual seasonality, but are being logged as Covid-19 hospitalizations this year.

ICU capacity is down 22% since May

Second, the increased pressure on capacity isn’t just coming from increased demand for ICU beds but from decreased supply of them.

On May 27th, I wrote that:

…the state government reports that there are currently 1,257 ICU beds in Minnesota (of which 1,010 are in use) with another 585 available at 24 hours notice and a further 541 available at 72 hours notice, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2:

Source: Minnesota Department of Health

Compare that to Figure 1. The number of ICU beds immediately available is up by 15% from 1,257 to 1,440, which is good news. But the number of ICU beds available at 72 hours notice has fallen by 64% from 1,126 (585+541) to 408. As a result, Minnesota’s overall ICU capacity is down by 22% since May 27th. If we had now the ICU capacity we had in May, we would be at 48% of capacity, not 62%.

This second point is a particularly bitter pill for Minnesotans to swallow. When he issued a stay-at-home order on March 25, Gov. Walz said:

“The objective of everything we’re doing here is, it’s too late to flatten the curve as we talked about, the testing regimen was not in place soon enough for us to be able to do that, or expand it enough. So what our objective is now is to move the infection rate out, slow it down, and buy time so that the resources of the ICU and the hospitals and the things that we’re going to talk about today can be stood up to address that.”

In March, KSTP reported:

The state has about 1,400 ICU beds, in total, and the push is to get that total to 2,000 intensive care rooms by using existing space in hospitals and clinics.

On April 29th, when a peak ICU usage of 3,397 for June 29th was forecast, Gov. Walz said:

“I today can comfortably tell you that, when we hit our peak — and it’s still projected to be about a month away — if you need an ICU bed and you need a ventilator, you will get it in Minnesota.”

Minnesotans have made many sacrifices to ensure that adequate ICU capacity is there when it is needed. They were told it was. It now appears that this was not the case.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.