Minnesota should get rid of the hospital moratorium permanently

Gov. Tim Walz met with legislative leaders yesterday afternoon. No agreement was reached, so he sent lawmakers a post-meeting letter laying out what he wants in a special session:

Among his requests for Pandemic Response, Walz lists: “Addressing Hospital Capacity by temporarily reinstating bed moratorium waivers.” This is ok as far as it goes, but Walz and state legislators ought to go much further: they should abolish Minnesota’s hospital moratorium completely.

What is the hospital moratorium?

In 1984, Minnesota enacted a hospital construction moratorium. This prohibits the building of new hospitals as well as “any erection, building, alteration, reconstruction, modernization, improvement, extension, lease or other acquisition by or on behalf of a hospital that increases bed capacity of a hospital.” Whenever hospitals or provider groups propose an exception to the moratorium, the Minnesota Legislature requires the Department of Health to conduct a “public interest review.”

Researcher Patrick Moran explains:

“In its review, the Department must consider whether the proposed facility would improve timely access to care or provide new specialized services, the financial impact of the proposed exception on existing hospitals, the impact on the ability of existing hospitals to maintain current staffing levels, the degree to which the facility would provide services to low-income patients, as well as the expressed views of all affected parties. [Emphasis added]”

Moran continues:

“These reviews must be completed within 90 days of the proposed project. However, the public interest review is not binding. The Minnesota Legislature ultimately decides which exceptions are allowed to go forward. Except for the fact that the Legislature makes the final determination about each project, the public interest review process for new hospitals and hospital beds closely resembles CON statutes in other states. [Emphasis added]”

Why do we have a hospital moratorium?

The explicit aim of the moratorium is to limit the expansion of hospital capacity in Minnesota. It replaced previous Certificate of Need (CON) laws:

Moran says: “Policymakers hoped that the moratorium would be more effective than CON in reducing the growth of hospital beds.”

Why would policymakers want to do this?

The rationale for Minnesota’s hospital moratorium is no different from the rationale for CON laws. The only reason we favor the former over the latter is, as Patrick Moran points out, that we think it will be more effective at limiting hospital expansion. Policymakers want to do that – they claim – because otherwise medical providers would over-invest in capacity which would drive up prices, raise health care costs, and restrict access to these services for the poor.

This is a bizarre argument. The reason we don’t have a McDonald’s on every block isn’t because state government protects us from this but because it makes no economic sense for McDonald’s to expand capacity with no regard to the demand for it.

The moratorium had restricted hospital bed growth in Minnesota

The moratorium has succeeded in its intermediate goal of restricting hospital capacity in Minnesota:

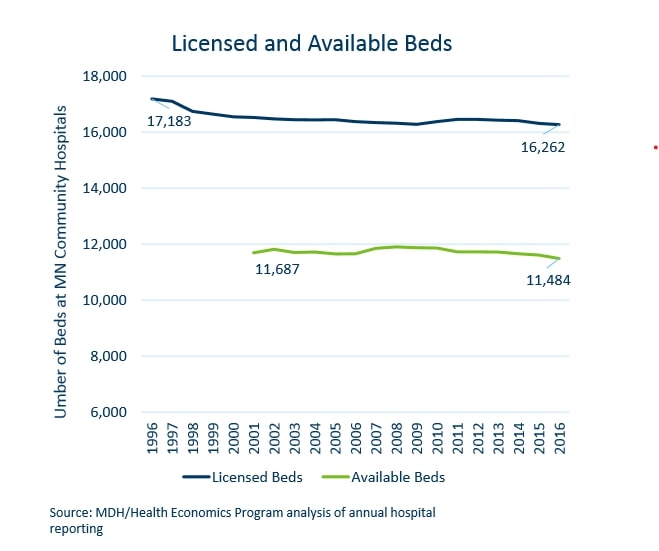

In the twenty years from 1984 through 2004, 16 exceptions were granted permitting just 94 additional licensed beds. As the chart below shows, between 1996 and 2016, the number of licensed beds in Minnesota actually fell by 921 while the population increased by 810,000. Exactly how “the Minnesota Department of Health has concluded that the moratorium is largely ineffective in restraining bed capacity”, as Moran says, is something of mystery.

The moratorium fixes the supply of beds. This encourages medical providers to shift them around in search of the best return. Moran explains:

“Many hospitals have strategically “banked” beds, allowing them to circumvent the review process. In 2005, while there were only 11,650 available beds, there were 16,392 licensed beds in the state, allowing many hospitals to rely on unused bed capacity when they expand services.”

This is why, as the chart above shows, in 2016 29% of licensed beds were unavailable.

CON laws and moratoriums fail to achieve their own aims

Policymakers presumably consider this a worthwhile price to pay for meeting the ultimate goal of protecting and expanding health care access for the poor. But CON laws and moratoriums fail even to do this:

…research finds that CON laws – or analogous laws like Minnesota’s moratorium – do little to increase access to health care for the poor, but, instead, limit the supply of such services. But then that is their express intention. As my colleague Martha Njolomole wrote last week:

“Findings show that controlling for other factors “CON laws seem to limit access to healthcare, fail to increase the quality of care, and contribute to higher costs.”

Additionally there is proof that repealing CON laws is highly beneficial to states.

“Researchers have found that states that have removed these rules have more hospitals and more ambulatory surgery centers per capita. They also have more hospital beds, dialysis clinics, and hospice care facilities. Patients in non-CON states are more likely to utilize medical imaging technologies and less likely to leave their communities in search of care. Though CON advocates sometimes claim that the rules protect rural facilities, states without CON laws have more rural hospitals and more rural ambulatory surgery centers than states with CON laws.”“

The moratorium should go for good

Minnesota’s hospital moratorium is bad policy at the best of times, COVID-19 has simply made its failure more acute. It succeeds in restraining the growth of hospital capacity, but fails to achieve its ultimate goal of doing anything positive for access to healthcare. The moratorium shouldn’t just go temporarily, it should go permanently.