The Coronavirus crisis shows that Minnesota must lift its hospital moratorium

The problem – Too few ICU beds

On March 25th, Governor Tim Walz announced a state-wide stay-at-home order running from March 27th to April 10th. He said this is necessary because if Minnesotans changed nothing about their regular routines, the state’s 235 adult intensive care unit (ICU) beds would all be occupied by a Coronavirus patient within six weeks. After nine weeks, the Minnesota Department of Health and the University of Minnesota models predict, the state would reach an epidemic peak of about 2.4 million infections, 60,000 hospitalizations, and 6,000 people in need of an ICU bed — far outstripping the capacity of the health system cope and driving the death toll up accordingly.

Happily, this doomsday scenario is already off the table because Minnesotans have taken some mitigating measures. Even so, this only buys us time. If the statistical models prove correct, those 235 ICU beds won’t be full until the 11-week mark, and the infection peak will come in 14 weeks rather than nine.

This shortage of ICU beds will be more acute in Greater Minnesota. Fox 9 reports:

Sixty percent of the counties in Minnesota don’t have an intensive care unit (ICU) bed, and eight counties don’t even have a hospital, according to data from Kaiser Health News.

There were only 243 intensive care unit (ICU) beds available in Minnesota as of Wednesday, and more than half are located in the Twin Cities metro.

…

One third of those testing positive the coronavirus in Minnesota live outside the Twin Cities seven-county metropolitan area, where the population is generally older, and more susceptible to CoVid-19.

Consider Aitkin County, where 41% of the population is over 60 years of age, estimated at 6,467 people. But there are only four ICU beds in Aitkin County, according to the Kaiser Health data. That means there are 1,600 people who are 60-plus, for every ICU bed.

The solution – Increase the number of ICU beds

With the extra time, Minnesota will work desperately to expand its ICU capacity. Local stadiums and hotels will be converted to temporary hospitals. “The attempt here is to strike a proper balance of making sure our economy can function; we protect the most vulnerable; [and] we slow the [infection] rate to buy us time and build out our capacity to deal with this,” Gov. Walz said.

Minnesota has made some encouraging early progress here. Last week, data released from the Minnesota Department of Health showed that the number of empty hospital beds available across the state rose from 1,941 on March 18th to 2,413 on March 22nd, an increase of 24%. The number of ICU beds went up by 20%, from 197 to 238 over the same period, and the number of beds that could be made available during a medical surge — when the pandemic strains hospital resources — went from 1,011 beds to 1,355, up 34% in just five days.

Obstacles – Minnesota’s hospital moratorium

Until 1984, Minnesota operated what were called Certificate of Need (CON) laws. These require government permission before a facility can expand, offer a new service, or purchase certain pieces of equipment. While Minnesota has not operated CON laws since 1984, along with two other states—Arizona and Wisconsin—it maintains several approval processes that function like CON laws.

In 1984, Minnesota enacted a hospital construction moratorium. This prohibits the building of new hospitals as well as “any erection, building, alteration, reconstruction, modernization, improvement, extension, lease or other acquisition by or on behalf of a hospital that increases bed capacity of a hospital.” Whenever hospitals or provider groups propose an exception to the moratorium, the Minnesota Legislature requires the Department of Health to conduct a “public interest review.”

Researcher Patrick Moran explains:

In its review, the Department must consider whether the proposed facility would improve timely access to care or provide new specialized services, the financial impact of the proposed exception on existing hospitals, the impact on the ability of existing hospitals to maintain current staffing levels, the degree to which the facility would provide services to low-income patients, as well as the expressed views of all affected parties. [Emphasis added]

Moran continues:

These reviews must be completed within 90 days of the proposed project. However, the public interest review is not binding. The Minnesota Legislature ultimately decides which exceptions are allowed to go forward. Except for the fact that the Legislature makes the final determination about each project, the public interest review process for new hospitals and hospital beds closely resembles CON statutes in other states. [Emphasis added]

Indeed, it is incredible to note that, as with CON laws, the purpose of this system is to make it harder to provide hospital beds in Minnesota. Moran says: “Policymakers hoped that the moratorium would be more effective than CON in reducing the growth of hospital beds.”

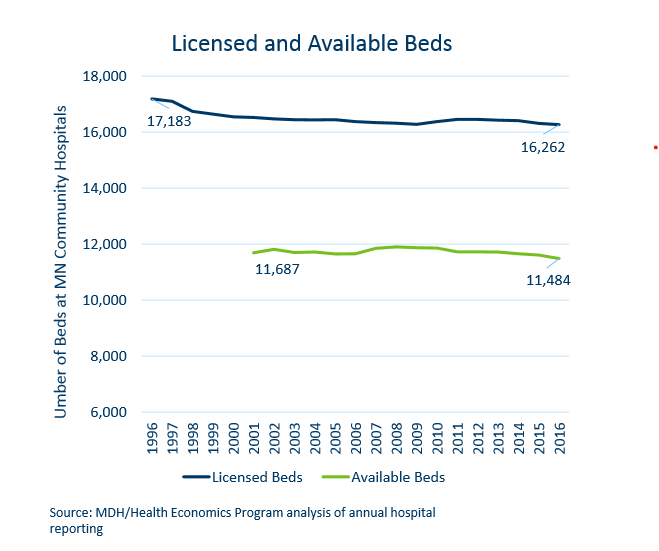

They appear to have been successful. In the twenty years from 1984 through 2004, 16 exceptions were granted permitting just 94 additional licensed beds. As the chart below shows, between 1996 and 2016, the number of licensed beds in Minnesota actually fell by 921 while the population increased by 810,000. Exactly how “the Minnesota Department of Health has concluded that the moratorium is largely ineffective in restraining bed capacity”, as Moran says, is something of mystery.

The moratorium fixes the supply of beds. This encourages medical providers to shift them around in search of the best return. Moran explains:

Many hospitals have strategically “banked” beds, allowing them to circumvent the review process. In 2005, while there were only 11,650 available beds, there were 16,392 licensed beds in the state, allowing many hospitals to rely on unused bed capacity when they expand services.

This is why, as the chart above shows, in 2016 29% of licensed beds were unavailable.

Why do we have this system?

No doubt, many Minnesotans would be wondering why state government seeks to limit the expansion of hospital beds.

The rationale for Minnesota’s hospital moratorium is no different from the rationale for CON laws. The only reason we favor the former over the latter is, as Patrick Moran points out, that we think it will be more effective at limiting hospital expansion. Policymakers want to do that – they claim – because otherwise medical providers would over-invest in capacity which would drive up prices, raise health care costs, and restrict access to these services for the poor.

This is a bizarre argument. The reason we don’t have a McDonald’s on every block isn’t because state government protects us from this but because it makes no economic sense for McDonald’s to expand capacity with no regard to the demand for it.

And, in fact, research finds that CON laws – or analogous laws like Minnesota’s moratorium – do little to increase access to health care for the poor, but, instead, limit the supply of such services. But then that is their express intention. As my colleague Martha Njolomole wrote last week:

Findings show that controlling for other factors “CON laws seem to limit access to healthcare, fail to increase the quality of care, and contribute to higher costs.”

Additionally there is proof that repealing CON laws is highly beneficial to states.

“Researchers have found that states that have removed these rules have more hospitals and more ambulatory surgery centers per capita. They also have more hospital beds, dialysis clinics, and hospice care facilities. Patients in non-CON states are more likely to utilize medical imaging technologies and less likely to leave their communities in search of care. Though CON advocates sometimes claim that the rules protect rural facilities, states without CON laws have more rural hospitals and more rural ambulatory surgery centers than states with CON laws.”

A cynic might ask ‘cui bono?’ First, note that the Department of Health’s public interest reviews “must consider…the financial impact of the proposed exception on existing hospitals [and] the impact on the ability of existing hospitals to maintain current staffing levels.” The system gives powerful insiders another advantage. Bed licenses can be held whether they’re used or not so a health provider can buy a hospital with 400 beds (medium sized by Minnesota standards), close it, but still gets to keep those licenses. They can move them elsewhere in the state or just hoard them to make it harder for other hospitals to come in to the market. This is how we ended up with “only 11,650 available beds [when], there were 16,392 licensed beds in the state.”

None of this is to suggest that without the moratorium Minnesota would have 6,000 ICU beds idling at all times in readiness for a pandemic. The costs of doing so would be vast and absorb resources which could be better used elsewhere. But we can be fairly confident that the number of ICU beds would be somewhat greater and our straits now would be somewhat less dire. In the longer term, with a population growing – albeit slowly – and aging more quickly, it makes no sense at all to block the expansion of hospital bed capacity. The moratorium achieves none of its goals at too high a cost. It should go.