Shellenberger: How climate activists caused the global energy crisis

The following article was written by Michael Shellenberger at Substack.

Shareholder divestment campaigns caused oil and gas shortages, a return to coal, and higher emissions.

Over the last decade, climate activists have successfully pressured governments, banks, and corporations to divest from oil and natural gas companies. At first such efforts appeared to be strictly symbolic. But in recent years years climate activists succeeded in driving public and private investment away from oil and gas exploration and toward renewables. The result is the worst energy crisis in 50 years.

Under-investment in oil and gas exploration is not the only cause of today’s energy crisis. The economic comeback from the covid pandemic has pushed up demand. Lack of wind in Europe meant higher demand for both natural gas and coal. And a drought in Brazil meant it had to import natural gas.

But the main cause of energy shortages is the half-decade-long under-investment in oil and gas driven by climate concerns.

“ESG [environmental, social, and governance] considerations account for much of the decline in capital expenditure by international oil companies in recent years,” notes The Financial Times today, “and the investor exodus out of oil and gas markets.” Bloomberg agrees, noting that “the market is now fixated on climate change and the dwindling appetite to invest in fossil fuels.”

China, India, the U.S., East Asia, and Europe are all mining and burning more coal to make up for the lack of natural gas. China’s government recently waived environmental safeguards on coal mining. China imposed rolling blackouts due to energy shortages while India narrowly avoided them.

Normally, the anticipation of higher oil and gas demand causes firms to increase investment in exploration. That hasn’t happened. The main reason, according to Goldman Sachs, is climate activist pressure on governments, firms, and banks to divest from oil and gas exploration.

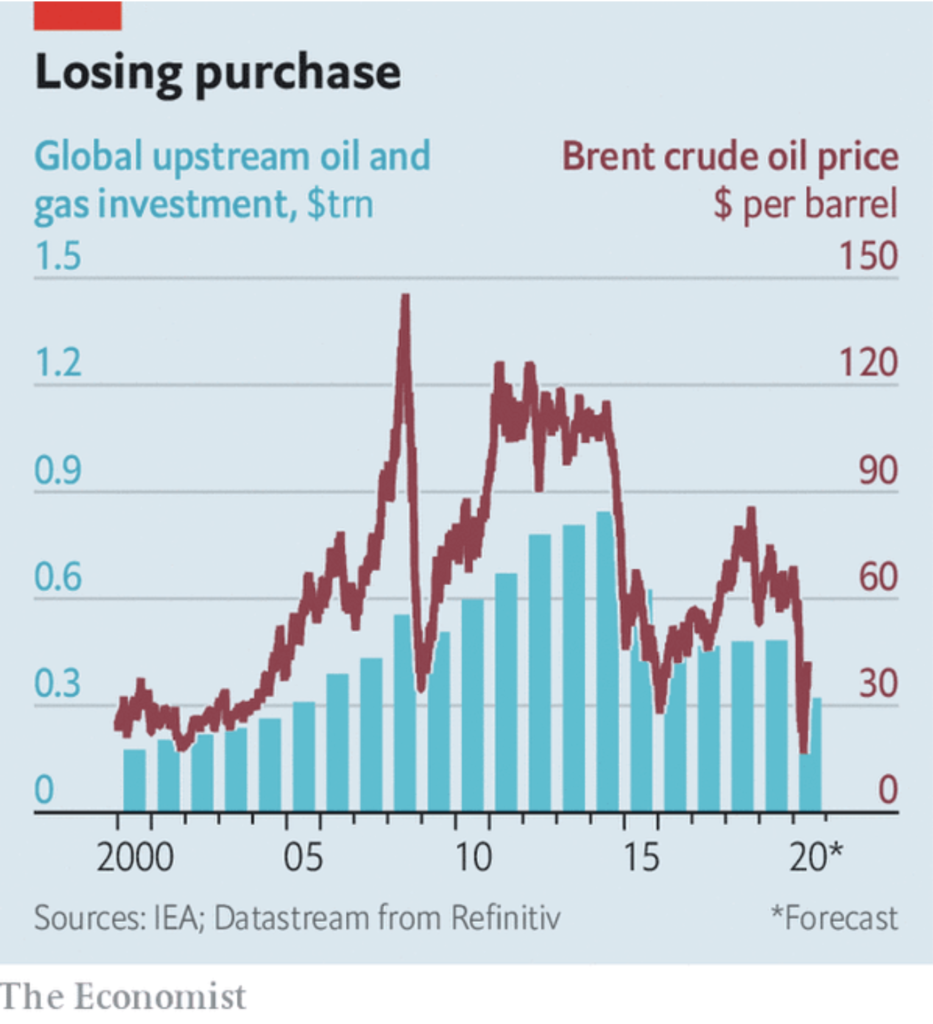

Oil and gas exploration investments declined by half between 2011 and 2021, notes The Financial Times. New oilfield discoveries fell to historic lows between 2016 and 2020, not due to lack of oil, but lack of investment in exploration. Today firms are spending 25 percent less than they need to hold oil production steady.

The result of successful climate activism is, paradoxically, rising coal use and carbon emissions. That’s because because electricity produced from natural gas produces about half of the emissions of coal.

Some of us warned that climate activist efforts against natural gas would backfire. Eight years ago I defended fracking for making natural gas cheaper than coal. Reducing natural gas exploration would make gas more expensive, I argued, and delay the transition away from coal.

Some worry that cheap oil increases its use, but petroleum use is highly inelastic, since our cars and trucks rely on it. Little oil is burned for electricity production, and natural gas is required to balance at the intermittency of solar and wind.

The proof is in the data. Fossil fuels’s share of global energy production remain unchanged at 84 percent since 1980. To the extent emissions in Europe and the US declined, it was largely due to the transition from coal to natural gas.

As a result of successful activist pressure, governments and investors have punished oil and gas companies. When an oil and gas exploration firm, EOG Resources, announced in February that it intended to expand output, its share price dropped more than any other company on the S&P 500. Naturally, American oil and gas firms have since refused to expand production, even as prices have risen.

Social responsible investing is decades old, but ESG was embraced over the last decade by large university endowments, investment banks like Blackrock, governments, the International Energy Agency, the United Nations and eventually by oil and gas companies themselves, including Shell, Total, and many others. In May, a court in The Netherlands ordered Shell to reduce its emissions, a ruling that made firms reluctant to invest in new oil and gas exploration.

It’s not like oil and gas executives didn’t know that underinvestment would lead to today’s price shocks. It’s that they were ignored. When the former CEO of Exxon, Lee Raymond, was asked what kept him up at night he said, simply, “Reserve replacement.” Shareholders had demanded he stop investing. In 2020, under pressure from climate activists, JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest investment bank, removed Raymond from his role as the board’s lead independent director.

Part of the problem is that neither corporations nor governments are taking the right actions. Some are going in the wrong direction. The U.S. Congress appears close to approving a deal to pour $500 billion into renewables and its enabling infrastructure over the next decade. Those taxpayer subsidies could further reduce the incentive for private firms to invest in oil and gas. Even if they don’t, the Biden administration has moved to restrict oil and gas drilling on public lands.

Meanwhile, even in the middle of the global energy crisis, the United Nations and the International Energy Agency (IEA), funded by developed nations, are putting pressure on nations to reduce oil and gas investments even more than they already have.

But high oil and gas prices will create political problems for governments as they worsen inflation. And prices are likely to remain high for years not months.

“Today, investment in fossil fuel is vilified and financing has become sparse as big western banks withdraw,” notes The Financial Times. “Due to long lead times between investment and supplies, we are yet to see the full impact of this slowdown in spending on conventional oil and gas production. In other words, supplies will continue to lag behind demand for the next few years.”

As a result, even as the Biden administration prepares to promote its heavy investments in renewables in preparation for United Nations climate change talks in Scotland, it is also pressuring OPEC to increase oil production.

“President Biden has effectively accepted the idea that the United States will rely more on foreign oil,” noted The New York Times. “His administration has been calling on OPEC and its allies to boost production to help bring down rising oil and gasoline prices, even as it seeks to limit the growth of oil and gas production on federal lands and waters.”

As a result, foreign nations will benefit from rising rising oil and gas prices at America’s expense. Saudi Aramco recently increased its investment in exploration and production by $8 billion. “Of course we are trying to benefit from the lack of investments by major players in the market,” its CEO said.

Increasing America’s dependence on foreign oil producers makes even The New York Times, which has long championed oil and gas divestment, nervous. A reporter there recently warned that “the United States and Europe could become more vulnerable to the political turmoil in those countries and to the whims of their rulers.”

Pundits are increasingly comparing President Biden to former President Jimmy Carter, and the 2020s to the 1970s. And, indeed, today’s energy crisis is eerily similar to what happened back then. Carter throttled oil and gas production, promoted renewables, and provoked a backlash that helped elect Ronald Reagan.