To climb tax rankings, Minnesota can reform its property tax base

Recently, I wrote about how Minnesota had slipped a place, to 46th, on the Tax Foundation’s 2021 State Business Tax Climate Index. This was largely driven by our state’s high corporate tax rates – where we rank 6th highest in the United States – and our individual taxes, where we rank 5th highest in the United States. To make serious progress up these rankings, we need to see these rates come down.

But there are other things drag Minnesota down on these rankings which would help us climb them if remedied. They are not huge changes such as cutting our corporate and income tax rates would be, but every little helps, as they say.

Yesterday, I wrote about measures Minnesota could take to improve its corporate tax base. But our state could also act to improve its property tax base.

Abolish Minnesota’s estate tax

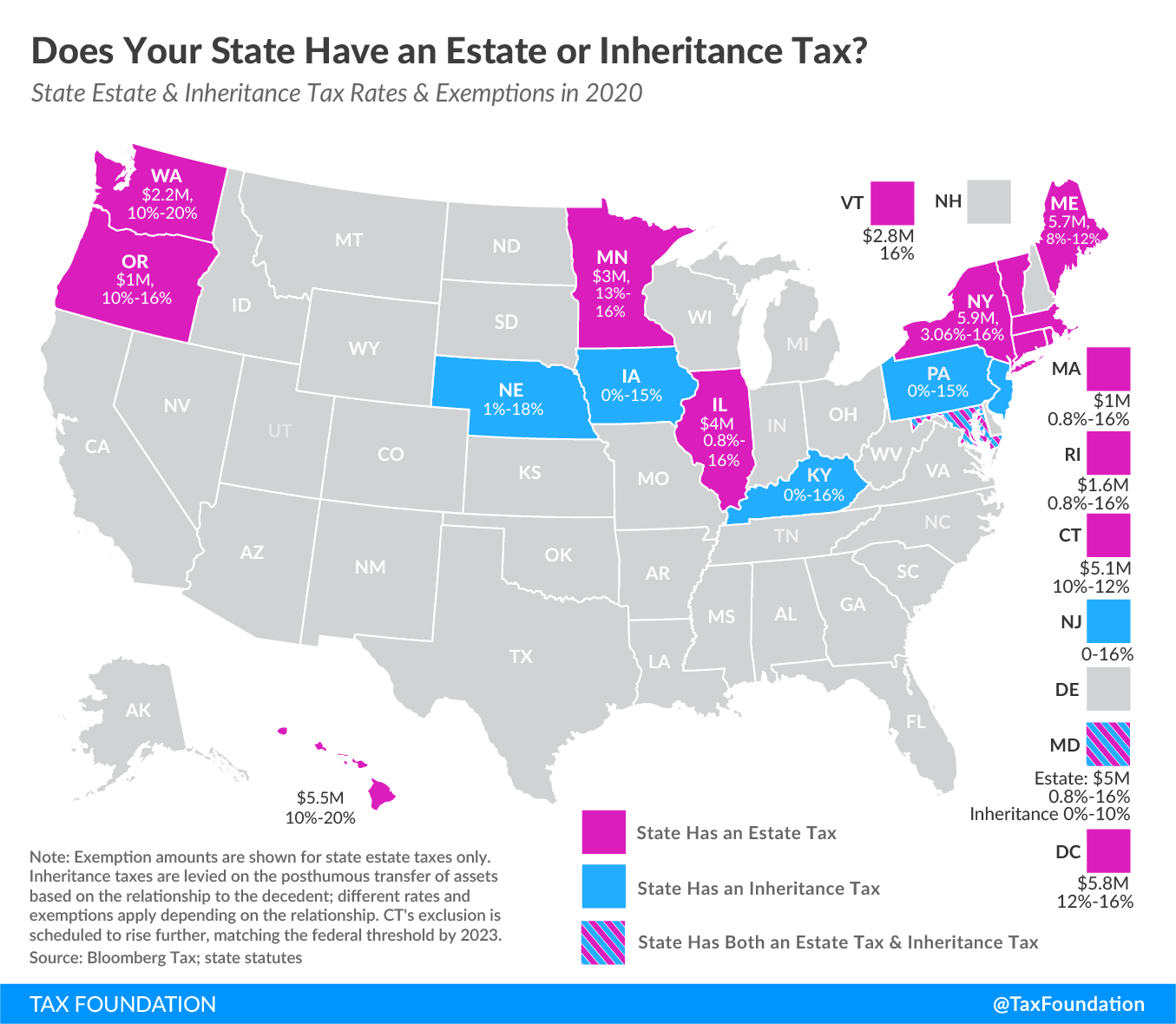

One of these measures would be to abolish the state’s estate tax. Minnesota is one of twelve states and the District of Columbia to impose estate taxes and further impose inheritance taxes. According to the Tax Foundation:

Estate and inheritance taxes are burdensome. They disincentivize business investment and can drive high-net-worth individuals out-of-state. They also yield estate planning and tax avoidance strategies that are inefficient, not only for affected taxpayers, but for the economy at large. The handful of states that still impose them should consider eliminating them or at least conforming to federal exemption levels.

The point about driving high-net-worth individuals out of the state is crucial in the context of Minnesota’s looming budget deficit. As I wrote in our report The Cost of Minnesota’s Estate Tax, Minnesota taxes estates more heavily than most states. Seven of the states that levy an estate tax and the District of Columbia have a higher exemption. The state’s starting rate of estate taxation—13.0%—is higher than any of the other jurisdictions that levy one. Its top rate is 16.0%. Only the state of Washington and Hawaii have a higher top rate.

As I’ve written before:

When taxes are high in one jurisdiction, people have an incentive to move to another one with lower taxes. We see people doing just this. The large and growing body of evidence on the effects of taxation on migration was summarized recently by economists Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais, Mathilde Muñoz, and Stefanie Stantcheva. They found that, “There is growing evidence that taxes can affect the geographic location of people both within and across countries. This migration channel creates another efficiency cost of taxation that policy makers need to contend with when setting tax policy.”

…

There is evidence that Minnesotans leave the state in response to these taxes. In 2013, the Minnesota Society of Certified Public Accountants surveyed its members and found that “more than 86 percent of respondents said clients had asked for advice regarding residency options and moving from Minnesota;” 91% said the number of clients asking about moving had increased from previous years.

When these people move, they take with them the future payments of income and sales taxes, among others. From the point of view of state government tax revenues, the question is whether the amount the estate tax brings in from those who stay is high enough to more than offset the lost revenues from these other taxes from those who go.

We found they probably aren’t. We estimated that, in 2015-2016 for example, the estate tax cost the state government $232.5 million in lost income and sales tax revenues.

A subsequent paper by economists Enrico Moretti and Daniel J. Wilson confirmed this:

In their paper, Moretti and Wilson studied “the effect of state-level estate taxes on the geographical location of the Forbes 400 richest Americans.” They then “estimate(d) the effect of billionaire deaths on state tax revenues.” “Surprisingly,” they concluded, “we find that the benefit exceeds the cost for the vast majority of states.”

But not for Minnesota. We are one of four states identified by Moretti and Wilson where the costs in terms of lost revenues from other taxes outweigh the benefits in terms of estate tax revenues. Those states are, coincidentally, the ones with the highest top rates of income tax: Hawaii, Minnesota, Oregon, and Vermont.

The purpose of taxation is not to bash the rich but to raise revenue to pay for government functions. Minnesota’s estate tax, by costing the state government revenue, actually makes this harder. Our estate tax should be repealed.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.