Abraham Lincoln on the meaning of July 4th

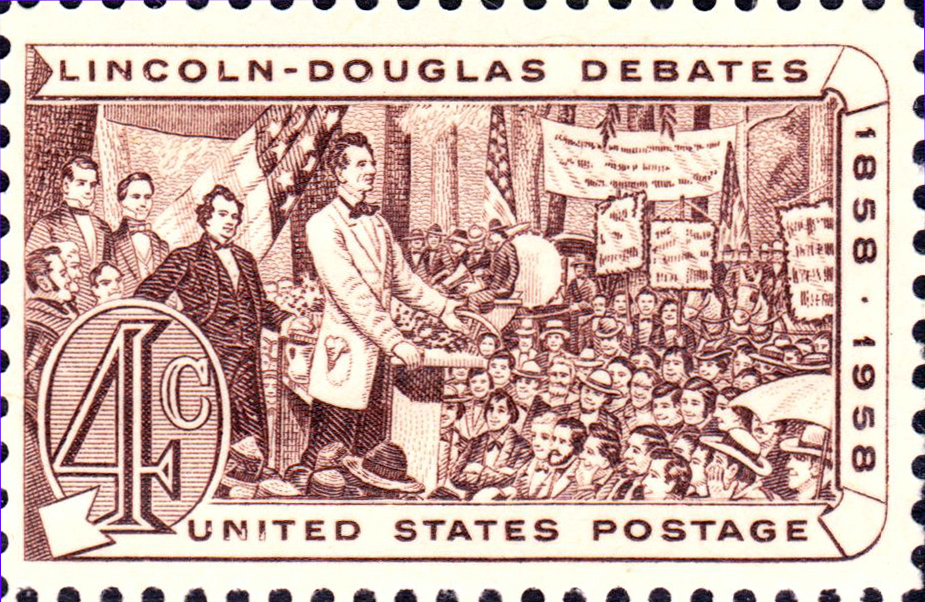

In July 1858, Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate, and the incumbent Democrat, Stephen Douglas, were locked in a tight race for one of Illinois’ Senate seats. The major issue in the race was slavery.

As the United States expanded, the question recurred whether the new states would be free states, which prohibited slavery, or slave states, which allowed it. The Republican Party had been founded in 1854 with the aim of either abolishing slavery or merely restricting it to the states which already allowed it. To supporters of slavery, restriction meant eventual abolition with more and more states joining the union. The Democratic party became the party of slavery.

Douglas proposed ‘popular sovereignty’ as a solution, whereby each new state would be able to decide for itself whether it would be a free state or a slave state. Lincoln opposed this. In a speech on June 16, he warned:

“A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided.

It will become all one thing, or all the other.

Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new — North as well as South.

This was the first entry in what became known as the ‘Lincoln–Douglas debates,’ a series of seven debates between the two candidates between August and October which examined the fundamental nature of the United States.

In another preliminary, a speech given in Chicago on July 10, Lincoln referred to the recent July 4th holiday and what it meant for all Americans, not just those who could claim an ancestor among the Continental troops at Lexington or Yorktown:

Now, it happens that we meet together once every year, sometime about the 4th of July, for some reason or other. These 4th of July gatherings I suppose have their uses. If you will indulge me, I will state what I suppose to be some of them.

We are now a mighty nation, we are thirty – or about thirty millions of people, and we own and inhabit about one-fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years and we discover that we were then a very small people in point of numbers, vastly inferior to what we are now, with a vastly less extent of country, – with vastly less of everything we deem desirable among men, – we look upon the change as exceedingly advantageous to us and to our prosperity, and we fix upon something that happened away back, as in some way or other being connected with this rise of prosperity. We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men, they fought for the principle that they were contending for; and we understood that by what they then did it has followed that the degree of prosperity that we now enjoy has come to us. We hold this annual celebration to remind ourselves of all the good done in this process of time of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it; and we go from these meetings in better humor with ourselves – we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way we are better than men in the age and race, and country in which we live for these celebrations. But after we have done all this we have not yet reached the whole. There is something else connected with it. We have besides these men-descended by blood from our ancestors – among us perhaps half our people who are not descendants at all of these men, they are men who have come from Europe – German, Irish, French and Scandinavian – men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here, finding themselves our equals in all things. If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us, but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,’ and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as through they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, (loud and long continued applause) and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.

Those immigrants, if they held to the principles of the Declaration of Independence, were as American as any blue blood, and Lincoln extended this to those Americans then held in bondage under the evil institution of slavery. As one of Lincoln’s successors, Ronald Reagan put it:

…since this is the last speech that I will give as President, I think it’s fitting to leave one final thought, an observation about a country which I love. It was stated best in a letter I received not long ago. A man wrote me and said: “You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.”

The ideals of the Declaration of Independence – “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” – are the glue that holds the people of this country together. They are what we honor today.